The syllabus for Michael F. Suarez, SJ’s Winter Quarter course, The Printed Book in the West: Evidence and Inference from Bibliography and Book History, was 27 pages long. It listed book after book that students would have the chance to see for themselves at the Hanna Holborn Gray Special Collections Research Center. The course, Suarez says, was like “an art history course given in a great museum. The holdings are that good.”

Ordinarily Suarez teaches at the University of Virginia, where he is a professor of English and director of its Rare Book School. A scholar of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century English literature, bibliography, and book history, Suarez came to UChicago during Winter Quarter as the inaugural Visiting Scholar in Paleography and the Book.

The new visiting scholar program, made possible by the support of Hanna Holborn Gray, Harry Pratt Judson Distinguished Service Professor Emeritus of History and former president of the University, will bring a guest professor to campus for one quarter each year. Visiting scholars—whose areas of expertise might include manuscript history and reception, paleography, epigraphy, philology, codicology, the history of the book and readers, or the evolution of print culture—will teach one course, deliver a public lecture, and conduct student workshops.

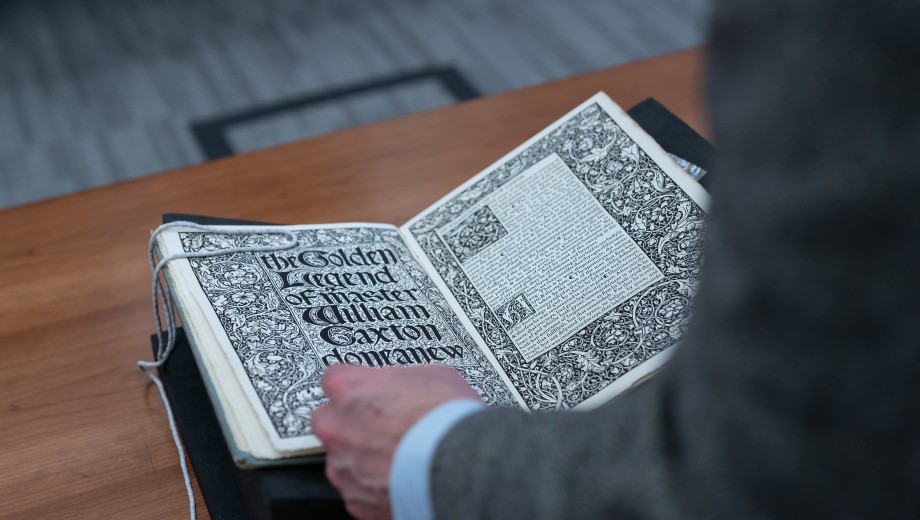

In December 2021, Suarez made a two-week reconnaissance trip to Special Collections, looking through its holdings and drawing up a short list for his syllabus. Each class session was primarily taken up with examining these rare books in detail. The oldest: a 1472 edition of Pliny’s Natural History, “printed in Venice by Nicolas Jenson in an elegant type beautifully reminiscent of Roman epigraphy,” says Suarez. The most recent: the 1930 Lakeside Press edition of Moby Dick, “powerfully designed and illustrated by Rockwell Kent,” he says. “This book, quickly issued in a trade edition by Random House, reinvigorated Melville’s reputation.”

The goal for the course was to teach students to read “the whole book,” Suarez says. “Not only the words on the page, but the page itself. The letterforms, paper, illustration, and mise-en-page.” Students learned about each book’s format, binding, publisher, and provenance (the history of its ownership), as well as the historical context in which it was published, circulated, and received.

“Bibliography is a form of literacy,” says Suarez. “Students who know how to read textual artifacts historically are able to marshal an interpretive richness and complexity that makes them better at what they do.” Although the course was listed in English Language and Literature and cross-listed in History, it attracted students from many other disciplines, including art history, music history, mathematics, history of science, and biochemistry and molecular biology.

Suarez’s public lecture as visiting scholar, “The Book as Museum in Eighteenth-Century Europe,” held at the Rubenstein Forum in February, focused on richly illustrated books of antiquities. The books, which were often styled as “museums” on their title pages, flourished at a time when public museums were becoming significant cultural institutions, he says: “It’s a fascinating chapter in cultural and intellectual history.”