During Winter Quarter, Michael F. Suarez, SJ, the inaugural Visiting Scholar in Paleography and the Book, came to UChicago to teach The Printed Book in the West: Evidence and Inference from Bibliography and Book History. Most of the class sessions were spent at the Hanna Holborn Gray Special Collections Research Center, where students were able to examine rare books in detail.

Suarez, a University Professor at the University of Virginia and director of its Rare Book School, is a scholar of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century English literature, bibliography, and book history. He spoke with Tableau about the rare books at UChicago, his print-digital agnosticism, and more.

To prepare for your course, you spent two weeks looking through the holdings in Special Collections. What were your best finds?

The first edition of Copernicus’s De Revolutionibus with annotations by Tycho Brahe is a marvelous association copy [a copy of a book that belonged to the author or someone connected with the author]. It also bears evidence of later expurgation: in nine places Copernicus’s assertions about heliocentrism are crossed out and altered to become theorems or hypotheses.

Réflexions sur la traite et l’esclavage des Nègres (1788), the exceedingly rare Paris edition of Ottobah Cugoano’s resounding condemnation of the slave trade, is a revelation in both its form and content. And the UChicago copy bears a single annotation, “par Condorcet.” It is entirely plausible, given his abolitionist activities, that the French mathematician and philosopher is the anonymous translator of Cugoano’s book, an intriguing possibility that bears further investigation.

In week three of the course, we looked closely at 18 editions of Euclid, from the 1482 Venetian editio princeps to a 1703 scholarly edition printed in Oxford. The richness of the University’s collections made such comprehensive study possible.

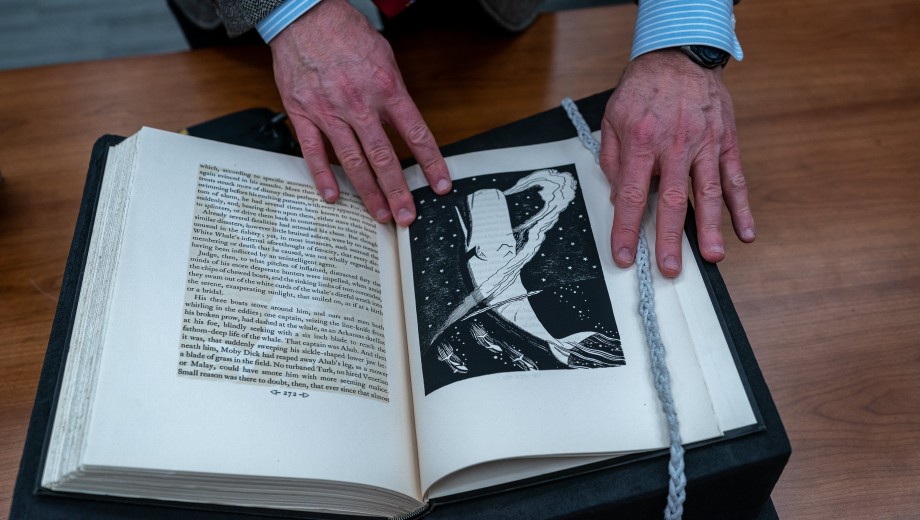

Finally, the M. C. Lang Homer collection (the Bibliotheca Homerica Langiana) is a bibliographical treasure that helps students not only to understand the transmission and reception histories of a foundational poet, but also to chronicle the history of printing, illustration, and scholarly editing in the West.

How did you get interested in bibliography?

I was enormously fortunate to be a student of Don McKenzie when he was professor of bibliography and textual criticism at Oxford. What led me to bibliography in the first instance was a problem in literary history: how, in eighteenth-century Britain, did the poetic canon come to be formed?

The answer was in no small measure tied to the business practices of London and Edinburgh booksellers: to appraisals of what would sell, to distribution networks, and to the vagaries of literary property. Pretty soon I was hooked.

Now, in addition to my own teaching and scholarship, I help direct the Rare Book School at UVA for the study of bibliography and book history. The school runs classes at nearly 20 other institutions ranging from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology to the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

What can scholars learn from physical books as opposed to digital versions?

That’s a big question! I will just say that digital versions are certainly necessary for scholarly study, but they are often not sufficient for bibliographical research.

Are there any archives in Chicago you want to visit while you’re here?

Beyond my own research in the Reg, I am also making good use of the remarkable resources of the Newberry Library. The two collections beautifully complement each other.

When you read for pleasure, what do you prefer—physical books, e-readers, or a mix of both?

Ever since I worked as a chaplain at Rikers Island—many years ago now—I have been an advocate for adult literacy. I am strongly in favor of whatever leads people to read.

The Rare Book School that I direct at the University of Virginia offers not only the courses Medieval Manuscripts and The Book in the Hand Press Period, but also Digital Forensics and Born-Digital Materials. It is foolish to imagine the relationship between print and digital as either/or. As you might imagine, I use digital tools in my scholarship every day, but I love physical books and, like most professors I know, I am an unreformed bibliophage.

In addition to your academic career, you are also an ordained priest.

I have been a member of the Jesuit order for 40 years. It is humbling—and a bit intimidating—to belong to a tradition of scholars and teachers that includes Christopher Clavius and Francisco Suarez, among others. I entered the Jesuits at 22, was ordained to the priesthood at 34, and received my DPhil at 39—an eloquent demonstration of being both dim-witted and intractable.