From antiquity to modern times, ghosts have served as cultural metaphors, storytelling devices, and figures in religious or afterlife beliefs. Faculty members Judith Zeitlin and Patrick Crowley explore the role of ghosts within their particular disciplines.

Judith Zeitlin is the William R. Kenan Jr. Professor in East Asian Languages and Civilization and the Committee on Theater and Performance Studies. Her teaching and research interests include Ming-Qing literary, visual, and cultural history, with specialties in drama, music, and the classical tale. A paperback version of her second book, The Phantom Heroine: Ghosts and Gender in Seventeenth-Century Chinese Literature, is forthcoming in December with a Chinese translation in 2017.

People ask if I’ve ever had a ghost encounter and then proceed to tell me about theirs. But I don’t believe in ghosts—I haven’t an occult bone in my body. My interest began with literature.

People ask if I’ve ever had a ghost encounter and then proceed to tell me about theirs. But I don’t believe in ghosts—I haven’t an occult bone in my body. My interest began with literature.

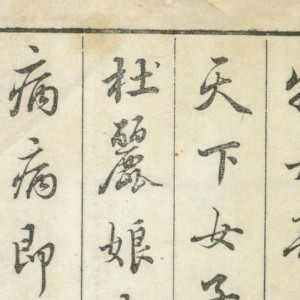

I wrote my first book on a Chinese collection of tales from the seventeenth century called Liaozhai's Record of the Strange. I was interested in a broader understanding of what the author meant by “the strange,” which wasn’t limited to the supernatural. The Phantom Heroine ended up being about the ghosts that I had exorcised from the first book.

What fascinated me was the Chinese emphasis on female ghosts. In many traditions, ghosts aren’t gendered. Our image of a ghost as sort of a floating sheet is a perfect example of our obliteration of human characteristics. But during the late Ming and early Qing dynasties, there was a veneration of love with great literature extolling the virtues of love, the power of love. But what is love? Love is not love unless it can bring the dead back to life.

So many of these ghost stories and plays are about love and sex. My book focuses on stories involving a living man having sex with a female ghost, bringing her back to life, though sometimes the act would kill the man rather than resurrect the woman. In fact, in a few cases these female ghosts could even bear living children.

One distinction between our conception of ghost lore and that of seventeenth century China is the intention of the ghost’s return. It’s not as much about vengeance as righting an injustice or fixing a perceived problem—such as rectifying an improper burial or a “bad death.”

A bad death—murder, execution, suicide—can prompt a ghost’s return. If a woman dies unmarried, that too is considered a bad death. She is an anomaly in much the same way ghosts are anomalies—spirits are not supposed to return in the normal course of things. In the Chinese patrilineal, patrilocal system, women belonged to other people’s families, in a sense; they married out of their natal family, entered new marital families as strangers, and rarely took the surname of the new family. If a woman died unmarried, she would have no one to perform her posthumous worship.

However, in Chinese literary ghost tradition, there are few stories about ghosts visiting their kin. The great ghost stories and plays are about meeting the ghosts of strangers—about romantic rather than familial love and obligations. Not all ghosts in Chinese literature are female, but women were more likely, based on Chinese family structures, to meet the criteria for returning after death.

Patrick R. Crowley is an assistant professor in Art History and specializes in the art and archaeology of the Roman world. His research interests include ancient optics, aesthetics, and phenomenological approaches to the matter of visual evidence. He is working on “The Phantom Image: Visuality and the Supernatural in Ancient Rome,” the first major historical study of ghosts in the art and visual culture of classical antiquity.

I first became interested in the depiction of ghosts not through ancient studies but from an exhibition about ten years ago at the Metropolitan Museum of Art that explored the links between spiritualism and occult photography in the nineteenth century.

I first became interested in the depiction of ghosts not through ancient studies but from an exhibition about ten years ago at the Metropolitan Museum of Art that explored the links between spiritualism and occult photography in the nineteenth century.

When I turned to my own field, I noticed that the vast majority of examples, most of them in funerary art, appeared around the second century CE, which coincides with a period the ancients called the Second Sophistic—a time when the fascination with Greek myth, philosophy, religion, and art played a crucial role in the shaping of an emergent historical self-consciousness in the Roman Empire.

Ghosts had special knowledge and could serve as a channel through which the past speaks in the present. A hero barely mentioned in the Iliad, for example, could come back to haunt the living and recount all sorts of events in the Trojan War that Homer “missed.”

Today we often speak of a “belief in ghosts.” But for the Romans, as for antiquity in general, belief was inferior to knowledge. It was more important at this time to have knowledge about ghosts than to simply believe one way or the other in their existence.

You therefore have learned men writing letters to their friends asking whether they think that ghosts exist or are simply the products of our imagination? But it’s more than simply wondering—they were looking for evidence, whether that evidence was based on hearsay or even higher standards of proof.

Visual evidence was paramount in this regard. Did you see something with your own eyes? And if so, how do you know that you can trust them?

For the ancients, the same words were used for ghost and image, whether pictorial, mental, or perceptual in nature. This raises the question: What is an image?

For the ancients, then, an image of a ghost is an image of an image. And it is precisely this redundancy—the way images of ghosts show us something about both what an image is and what a ghost is—that makes them look rather different from our modern ghosts.

For rather than depicting ghosts as luminous and semitransparent phenomena as we find in the gothic imagination of the romantics or the spirit photographs of the nineteenth century, the ancients insisted on their superficial, if elusive, solidity.

Comments

ghost literature

how many ghosts are left in Chinese culture today, in its socialist modernity; or are ghosts ephemera about feelings of dissent or irresponsibility to rule. Having taken one of Professor Zeitlin's courses (2002-'03) on purity, ghosts and society, and the Han genotype of the scholar and maiden, as deviant forms of culture on the periphery of Buddhism, aesthetics, and the institutionalisation of marriage, I do have a feelingn of ghosts as an evasion of death. Perhaps we need them as vernacular proofs of working society, and perhaps we need them as a dream-catchers of the soul. There is at the very least indigenous concepts from anthropology that we as scholars can employ to denote that ghosts are often histories of persons whose pysche renders an event that is up to judgement rather than just a personal token. It's good to see some dialogue about the indispensability of ghosts and their archetypes in culture. I expect always, Chicago.