Fresh out of college and on his first trip to India, Philip Lutgendorf quickly became addicted to chai—“a rich dairy concoction that is heavy on the dairy, usually heavy on the sugar, and also heavy on the tea.” That was in 1971. Returning as a graduate student to study Indian epic narrative and performance, he says, “I fell into the habit of taking chai, and I always thought that it was an inescapable and immemorial part of Indian life.”

Fueled by the chai he drank at street-side stalls and at home in his Iowa kitchen, Lutgendorf (AB’71, AM’82, PhD’87) became a professor of Hindi and modern Indian studies at the University of Iowa. He also produced two highly regarded books. The Life of a Text (1991) examines popular performance of the poet Tulsidas’s retelling of the epic tale of the Ramayana, and Hanuman’s Tale (2006) looks at popular worship of Rama and Sita’s devoted monkey helper.

For years, Lutgendorf assumed that tea drinking was “as Indian, and perhaps as old, as the Vedas,” or ancient Hindu scriptures. But when his interest in food, drink, and material culture led him to investigate the topic, he was surprised to discover that chai as Indians drink it today has a relatively recent history. “In many places in north India—places we now think of as being the tea belt and the real heartland of tea popularity—the drink was only introduced in the 1960s and ’70s or even later,” he says. “That made me think, ‘Well, there’s an interesting story here to be told.’”

Lutgendorf landed a Fulbright-Hays faculty research award in 2010–11 to gather material for a book on the social history of chai in India. The early years of that history are well documented. Gandhi and other nationalists criticized tea as a foreign and imperialist product. Before British rule, the Mughal courtly elite consumed tea in small, medicinal quantities. “It was a rare substance,” he says, “almost certainly imported from China, perhaps via Iran.” As the British developed the tea habit and expanded their global empire in the late eighteenth century, they were eager to break China’s monopoly on tea production. In the 1830s, they began cultivating an indigenous tea plant in the hills of Assam and Bengal, in northeast India, and used indentured labor to build a vast system of plantation agriculture. By 1888, India surpassed China as the main exporter of tea to the West, but it was the British—not Indians—who craved the drink.

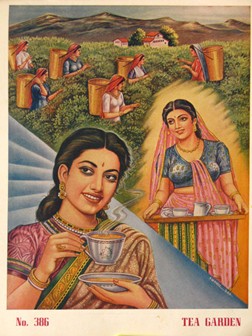

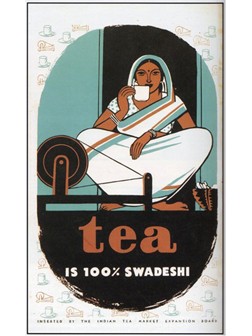

Tea producers saw no need to cultivate a domestic market in India until the Great Depression, when British consumption fell and advances in production generated a tea surplus. In 1936, the Indian Tea Market Expansion Board launched an aggressive marketing campaign to get ordinary Indians hooked on the drink. Free samples of brewed tea were proffered in railway stations and public markets; promotional posters and literature demonstrated the “correct” (that is, English) way to brew and serve tea. The campaign’s rhetoric was not subtle; in his archival research, Lutgendorf found promotional materials that “assume the triumphalist tone of Christian missionary tracts, suggesting that the quintessentially English beverage will rescue its Indian consumers from ‘lassitude’ and vice, and will inculcate in them such desirable traits as punctuality, decorum, and good sanitation.”

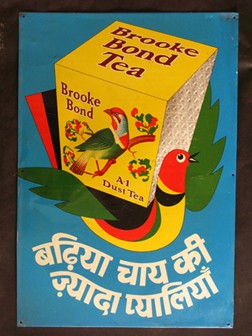

South Asia’s first mass marketing effort lasted two decades, but it had limited success, in part due to political opposition. Mohandas Gandhi and other nationalists criticized tea as a foreign and imperialist product. After independence in 1947, tea estates and wholesaling companies slowly passed from British to Indian hands. The major tea companies, now owned by Indians, sought to convince consumers that tea drinking was not only swadeshi (of the country) but also “conducive to both individual and national health and civility.”

Technology played a crucial role in bringing affordable chai to the masses. Simpler machinery made the processing of CTC leaf (cut/crushed, torn, and curled) tea cheaper by the late 1950s. Factories could now produce “quick brewing teas of deep color and robust flavor, that could stand up to copious draughts of milk,” writes Lutgendorf, and that tasted strong and delicious whether boiled, simmered, or blended with sugar and spices by a housewife or street vendor.

Today, about 80 percent of the tea produced in India is consumed in the country. Small, sweet, milky cups are sold and served at all hours of the day in homes, offices, shops, and on the street. Chai prepared in this manner is now “the proletarian beverage par excellence,” Lutgendorf writes, the daily fuel of office workers and informal-sector laborers and “the de rigueur hospitality offering to visitors.” Global chains like Starbucks sell their own version, although it “doesn’t taste anything like the chai you get in India,” says Lutgendorf. “Chai in America tastes like pumpkin pie.”

To chronicle the triumph of tea, Lutgendorf scoured Indian archives for materials in Hindi and other languages; he also did ethnographic research. “A lot of important developments in the popularization of tea are simply not documented in print sources,” he says. “You have to go to oral history.” In Calcutta, he visited well-loved tea shops and interviewed the proprietors. And in Mumbai, he trekked to parks where elderly people stroll and congregate in the early morning, to collect their stories about how tea was introduced in their family, village, or area. “I would just walk up as if from Mars and say, ‘Excuse me, I’m a foreign researcher,’” he says, laughing. “And most of the time people were very, very friendly and quite willing to talk.”

Lutgendorf considers his research on chai to be a “tea break” from his scholarship on the great Indian epics. (He also teaches and writes on Indian cinema.) Over the next several years, he will be preparing a new translation of the Hindi version of the Ramayana for the Murty Classical Library of India and Harvard University Press. Meanwhile, tea provides a refreshing change of pace and “an intriguing ‘lens’ through which to focuson other changes associated with ‘modernity’ in twentieth-century India.” The spread of tea accompanied changes in lifestyle, rural-to-urban migration, and urbanization, he notes; it paralleled the rise of middle-class culture, marketing, and consumerism.

When Lutgendorf explains that chai is, “in the longue durée of Indian history, a very recent development,” he says that most Indians respond with the same surprise he felt when he first began his study. “They get this puzzled look and say, ‘What did we drink before?’” With time, he found the answer: “Chai really didn’t replace anything. It created a new niche for itself as a very inexpensive social beverage that could be freely shared.”

Images courtesy of Philip Lutgendorf; the Priya Paul Collection, New Delhi, and Tasveer Ghar; and the Hiteshranjan Sanyal Memorial Archive, Centre for Studies in Social Sciences, Calcutta.

Comments

no need to boil

I am a true chai addict, and my beloved Lipton's Premium Darjeeling is no longer available in the States. I will surely need to check out Assam CTC. For now I'm using Liptons yellow label, an inferior tea or what they called "gun powder", made with Ceylonese tea, but it's not the same quality as the leaf tea, and works on my system too hard. Some Indians prefer it, well boiled. I don't boil my chai, only the water and milk. I leave the ginger to seep along with the tea, for about 7 minutes. I also add immediately, cardamom, a smashed cinnamon stick or two,a couple smashed cloves, and sometimes smashed peppercorns. After grating the ginger I slam all of the spices with a heavy cast iron frying pan, which does the trick with less effort than a mortar and pestle. I think I enjoy my morning chai better than anything else I consume the rest of the day.

Elixir of life!

A few years ago I gave away my coffee, filters, grinder, pots, press, maker and related devices, and started feeding my chai habit daily, not just while in India in the winter but the rest of the year too. The only trouble is, the best chai is made from fresh raw warm creamy buffalo milk, and I can't get any in Alaska. I like it with chai masala but it's fine plain. How does anyone manage without! I agree about the "pumpkin pie" effect - perhaps people think that's what chai really is supposed to taste like. AMBKJ, sometimes I drink from the saucer.

Wonderful piece!

Fascinating and so well written. Thank you!

Chai

Thanks! I am going to make Chai. Great article, informative. I liked the slides of the posters and great picture of you with monkey. I hope he/she got off you nicely and willingly.

Nicholas Pogany, UofC (long time ago)

Tea from Darjeeling

Last summer, I bought a kilogram of Rose tea in Darjeeling. I am not really a tea drinker but I really do love this tea. It is light and has a lovely fragrance. it requires little or no sugar.