Patrick Jagoda is William Rainey Harper Professor in Cinema and Media Studies and English Language and Literature as well as the author of several books on game studies. He is cofounder of the Game Changer Chicago Design Lab, the Fourcast Lab, and the Transmedia Story Lab, and he serves as faculty director of the Weston Game Lab and the Media Arts and Design program.

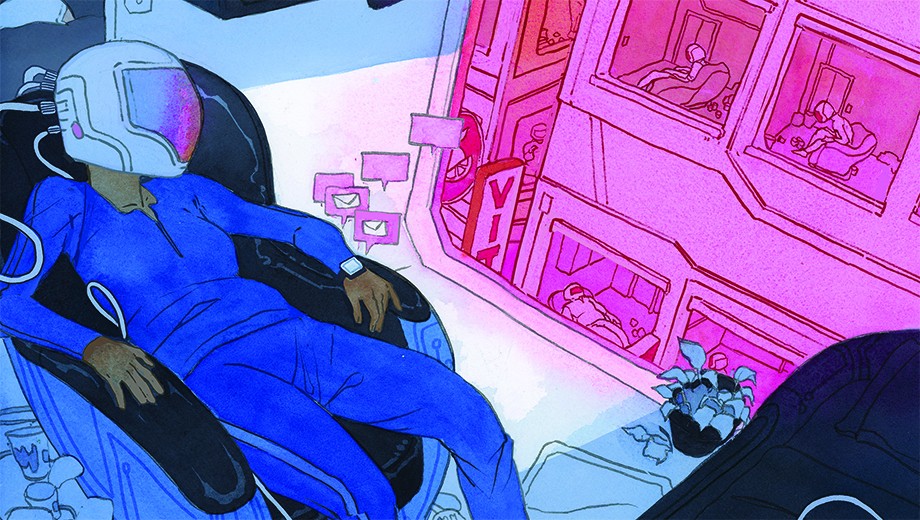

Since the start of the twenty-first century, video games have moved from subcultural hobbies marketed to a narrow demographic of White adolescent boys to one of the world’s largest cultural phenomena. By some estimates, there are currently over 3.2 billion global gamers. The game industry in 2022 was estimated to be worth 347 billion US dollars, substantially exceeding the film and music industries.

Given the popularity of video games, there is ongoing curiosity about whether games are culturally destructive or socially redemptive. Parents ask me if their children should even be playing video games at all. Teachers ask me if there are uses of games in the classroom that exceed the “chocolate-covered broccoli” approach of some unengaging educational games. Instead of taking an extreme view, either cheerleading or condemning, we can better grasp the medium of games by examining it critically—and by remaking it through imaginative design.

Games are a complex form and metaphor in our twenty-first-century world. People play games for many reasons. Games can be fun. They can offer a safe space in which to encounter a surmountable challenge. Many games provide social experiences, either in person or remotely. Still other games are essentially interactive narratives that spur interpretation, much like novels or films. One reason that games resist any easy characterization is that so many different kinds of things, in 2024, can be called games. This includes a gamified learning system like Duolingo, sandbox spaces like Minecraft, and even escape rooms.

Since I joined the faculty, much has changed in games research at the University of Chicago. We now have a Media Arts and Design major with a game design emphasis. I have also cofounded three labs that demonstrate just how versatile a form games have become. First, the Game Changer Chicago Design Lab, which I started with [then] medical professor Melissa Gilliam, creates games as educational tools to improve public health; encourage underrepresented youth to pursue STEM pathways; and explore race, gender, and sexuality. Second, the Fourcast Lab, which I created with theater and performance studies professor Heidi Coleman [AM’08], designs artistic “alternate reality games” with science faculty about topics such as climate change and epidemiology. Finally, the Weston Game Lab, a student-facing initiative I run with game designer Ashlyn Sparrow, provides resources to—for instance—a student who wants to understand the history of Japanese role-playing games; a collaborative team that seeks to create an entertainment game; or a research group in public health, quantum computing, or financial education.

As the infamous (though unofficial) motto of the University of Chicago once boasted, this is the place “where fun goes to die.” Yet in 2024, this could not be further from the truth. Numerous members of the University community have transformed the life of the mind into a life of play. As any serious teacher will tell you, play (including gameplay) can be the highest form of learning.

Ghenwa Hayek is an associate professor in Middle Eastern Studies and coleader, with associate professor of Islamic studies Alireza Doostdar, of Gaming Islam, a research initiative that explores representations of Islam, Muslims, and the Middle East in video games. The project began with an eight-part video series on the game Call of Duty: Modern Warfare.

I declared to anyone who would listen that, after I got tenure, I would be playing video games for a good amount of my time. And one of the things you realize when you start expressing an interest in video games is that lots of other people play them too—they just don’t usually talk about it. That’s how I found out that Alireza Doostdar [associate professor of Islamic studies and the anthropology of religion in the Divinity School] also plays games.

We’re both really interested in taking our scholarship to a public that we usually don’t reach. One model for public scholarship we thought of was Jack Shaheen’s book Reel Bad Arabs [Olive Branch Press, 2001] and subsequent documentary, which deconstruct the way that Arabs are represented in film and on TV. Gaming Islam develops Shaheen’s book and similar projects for a different kind of audiovisual medium. It’s disheartening (but not surprising) that so many of the stereotypes that were identified in earlier decades are still present in contemporary games’ representations of certain kinds of Middle Eastern people.

We started with Call of Duty because it’s a behemoth franchise. You can’t ignore it. I was surprised at how much I enjoyed playing Call of Duty: Modern Warfare. The gameplay is amazing. I had the impression going in that it’s just a game about killing a bunch of people, which it is, but it’s also very well crafted and has compelling characters. And that’s one of the reasons we need to pay attention to games like this—because it’s so fun to play and so easy to get sucked into the story. Fundamentally, though, it’s not very different from a lot of mainstream American media produced about the region.

Of course, in the same way that indie films are different from Hollywood blockbusters, there are massive games produced by big studios, and there are also lovingly crafted indie games made by one person or a very small team. Our next series for Gaming Islam is going to focus on one of those small games, called Heaven’s Vault. The protagonist is a Muslim archaeologist named Aliya who wears the hijab. In many ways, she is the antithesis of the swashbuckling archaeologist represented by Indiana Jones on film and Lara Croft in an earlier generation of video games. Yet even that game, we will argue, carries some familiar ways of thinking around knowledge production about the East—specifically about artifacts and who gets to decipher the language and who gets to explain a culture. That’s a little bit of a spoiler!

My personal ambition for Gaming Islam is that it will reach people who have started to pick up games and are beginning to question some of the representations they’re seeing of Muslims and the Middle East. A young person could watch our videos and realize there is a deliberate choice in making the people in Call of Duty look or speak a particular way. And why is the hero always an American soldier saving locals from themselves?