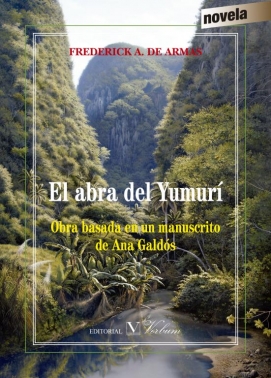

When Frederick de Armas was a child, his mother, Ana Galdós, began writing a novel that she never finished. De Armas, the Andrew W. Mellon Distinguished Service Professor in Romance Languages and Literatures, studies and teaches the great works of the Spanish Golden Age. He has also devoted the last several years to creating a complete book from his mother’s notes: El abra del Yumurí (roughly, The Yumurí River gap, Verbum, 2016). Tableau is pleased to present a translated excerpt of the book, a sort of murder mystery set in pre-Castro Cuba.

It was just a small parlor, situated on the corner of a somewhat dusty apartment with worn furniture and yellowed green wallpaper; but even so, it was an inviolable place. There the three unsavory dames came to play canasta every third Friday of the month, and each time they invited a different victim. In truth, they also played in other places, but this was the parlor that conserved the magic of the ancients. Though they had neither money nor beauty, these three 50-somethings knew very well they were indispensable at any society party in Havana. No one would dream of not inviting them, for the consequences would be devastating, fatal.

That October day, the three canasteras were highly offended because their special guest had not come, while they had arrived on time, even early. They had arrived early because they wanted to squeeze as much juice as possible out of their very flavorful guest; but there they were, abandoned by that very woman. She would pay for her misdeed.

That October day, the three canasteras were highly offended because their special guest had not come, while they had arrived on time, even early. They had arrived early because they wanted to squeeze as much juice as possible out of their very flavorful guest; but there they were, abandoned by that very woman. She would pay for her misdeed.

The three sighed at the same time and prepared to weave a blanket with outlandish figures, while the cards remained on the table. The two of spades signified past or future robberies and violent crimes; the two of diamonds, new passions; while the queen of clubs had to be the Countess. Clotilde had let the deck fall and this was all it showed; she had let it fall on that table so precious to the three canasteras, a table of very expensive woods with incrustations of marble and black opal, and adornments that impressed others. Three black chairs with leather backs comforted them. The fourth was empty.

The guest who sat there would be able to observe the only decoration in the parlor. It was a painting darkened with age. Though all their guests doubted what the three canasteras told them, they kept it to themselves, knowing how vengeful they were. No one, ever, questioned the absurd statements of these three dames. They declared that the painting was the most reliable version of The Spinners by Velázquez. With that they felt very much mistresses of culture.

For a long time, they had admired that precious art object for which they paid all the money they didn’t have. Lamerens, the antiques dealer of Matanzas, assured them it was an original. A few of their guests had dared to point out it was missing a figure, that of Pallas Athena, the goddess who had condemned Arachne for defying her. Arachne was without a doubt the best of the weavers, and her depictions of the lovers of Jupiter were fascinating. This version didn’t limit itself to depicting only one of the god’s lovers. The artist drew several of them in order to do justice to Arachne’s art. And they, the three canasteras, considered themselves, among other things, successors of Arachne.

Their function in Havana society was to coax out all its secrets, be they of love, fear, ruin, or violence. They gathered a sigh here, a look there, and a word that escaped from the mouth of someone in the delirium of a party. Anything that was let slip in a game of canasta served as the basis for all their gossip. All these threads they went on weaving into realities they whispered to the world. No one wanted to be part of the three canasteras’ tapestries of gossip and intrigue.

Because of that, the residents of Havana always brought them delicious bits of slander, anything they knew about other people in order to save themselves, to in this way remain outside the tapestry. And the canasteras were very proud of their tapestries. Some were rather scandalous. They insinuated little things about the secretary of the Countess or the daughter of an important figure. Other threads were fatal, since they spoke of the Commander with his black boots and cigarette case covered in human skin, procured from the dead or victims of torture in his dungeons. They whispered very secretly the dark desires of that cruel and vicious being.

On his sister Felicia, they were still finding out many juicy impertinences; and on that conceited Carolina, on her they would take revenge. She thought she was so smart with her little newspaper articles. She thought she was such a fine lady with her grandiloquent surnames. But they sensed scandalous circumstances in her past. There was much to find out. And what could be said about the previous murders? Well, the murders had continued to be committed without the police solving them. How had they managed to disappear those society women? And how come they kept on appearing, dead in the wrong places? Was the Commander covering something up?

Clotilde seemed to know something about it, but said nothing. Although the three canasteras had only to look at each other to know the plots the others were hatching, in order to guess the gossip they were preparing—in this case, no. In this case, there had been suspicious silence. They never spoke of the assassin known as “the silk handkerchief killer,” for his signature was to leave a silk handkerchief covering the mouth, inside the mouth—or even deeper inside, in the victim’s throat. Nothing about this was ever spoken. But that afternoon, Clotilde broke the silence and whispered:

There’ll be a cadaver,

Abracadabra,

Open cadaver,

Abracadabra,

Open cadaver,

There’ll be a cadaver,

Silken victim,

Silken hands.

Abracadabra

There’ll be a cadaver.

The other two canasteras looked at each other in surprise, but went along and immediately tried to forget those fateful words. Instead, they focused their attention on other scandals, on other mysteries. What about those Americans, those Mr. Smiths and Mr. Joneses that came to do little things they wanted to hide? Well, that wasn’t so important. It was already well known why they came to Cuba. And what news of the parties or immoral bacchanals that happened one after another, while gunfire and bombs broke out all over the city? They already had much to weave. Everything would be revealed in its propitious and terrible moment. Their tongues would be scissors. And Clotilde would cut the string. Meanwhile, they’d dance to the mambo rhythm of gossip.

Excerpted from El abra del Yumurí, by Frederick de Armas. Copyright (c) 2016 by Frederick de Armas. With permission of the publisher, Verbum. All rights reserved. Translated by Lucina Schell.