Art historian Christine Zappella Papanastassiou, AM’15, PhD’22, is an adjunct assistant professor of neurosurgery at the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio, where she conducts interdisciplinary research on human perception and teaches art history to health-care practitioners. She spoke with Tableau about Renaissance Italian painting, the human body, and the unlikely path that led to her having an ID badge in a neurosurgery department.

How did you get interested in the study of perception?

There has been a trend in art history toward examining the sensory environment and the individual person’s place in it. My dissertation was on the Cloister of the Scalzo, a small cloister in Florence that [members of a Renaissance-era confraternity] would walk through as they moved into and out of a space in which they did religious ceremonies, including self-flagellation. They would do these things in the dark and then emerge into this cloister that was sparklingly bright. If we don’t think about that experience, and we just talk about the paintings as if they exist on a wall with no context of a viewer, then I think we’re really missing a lot.

This point was brought home to me even more as I was working in museums like the National Gallery of Art and the Art Institute of Chicago. You really had to think about how a person encounters the works of art. How do the works in a room talk to each other? How do the rooms talk to each other? And how are people moving about in these spaces?

This led you to study medicine?

In art history we have this concept called the “period eye,” where you look at lots of art and you begin to understand the tastes of the people from the period. What I began to understand is that the period eye is disembodied. To put the period eye in a body, I was going to have to pay careful attention to real bodies, and in an interdisciplinary way.

First I realized that, as an art historian, I had no idea how we even see. So I started with basic research on human perception. I was drawing from biomedical sciences and from psychology. I rapidly realized that I could not be an expert in all these fields. I was going to have to get collaborators. I started sending cold emails to scientists—and they loved it! They would say, “When I look at art I always think about these things.” They were so generous, and they would send relevant articles and put me in touch with other experts.

How have these scientists made you think about art differently?

They’ve pointed out phenomena that I was totally missing. I was imagining the flagellants as they moved out of this dark space, where they had beaten themselves for a long time, and into the bright cloister with these paintings. And I thought the brightness would wash out the images and it would have this effect like an epiphany. I got in touch with a vision researcher who said, “That’s definitely happening. But you know what also might be happening? The dazzling light might have a sensory perception effect that dulled their pain.” It seems this cloister was designed to bring out multiple effects to make it feel as if they were having an experience of divine healing.

The paintings in the cloister, which depict scenes in the life of St. John the Baptist, are monochrome. What are the effects of viewing a painting in gray scale?

The Cloister of the Scalzo was created by one of the most important Renaissance painters, Andrea del Sarto, throughout the course of his entire adult career—it took him 16, 17 years. His fame lies in his ability as a colorist. So why is his most major monument in monochrome? I eventually decided that I couldn’t answer that question, but what I could do is study the effects of monochromy.

Everyone loves that moment in The Wizard of Oz right when Dorothy opens the door to Munchkinland and goes from being in black and white to color, because there is a sense in which color is a fuller reality or hyperreality. Things in black and white have the feeling of being drained of something. They exist on a different ontological level. Monochrome also seems unfinished. We accept in modern times that things can be left unfinished. All of Rodin’s work looks unfinished, and we love it, but he’s playing off of Michelangelo, who was literally just not finishing his work.

Why would you want something to look unreal or unfinished?

In the Renaissance there is major anxiety about idolatry. They are concerned about being tricked by images—especially in a sexual way. They’re moving into an age of increasing naturalism, where things start to look the way they actually look in the world. And they are really, really concerned about sodomy. The last thing they want is for you to see a sexy, full-color, life-size image of Jesus and have a sexual reaction.

Also, because monochromy connotes reality in a state of unfinish, it gives people a space in which identities can be negotiated—in which you are going from one state of being into another. These paintings are in religious spaces where you’re going to perform a ritual that’s going to somehow change you.

Your husband, Alexander Papanastassiou, is a neurosurgeon. Is he one of your collaborators?

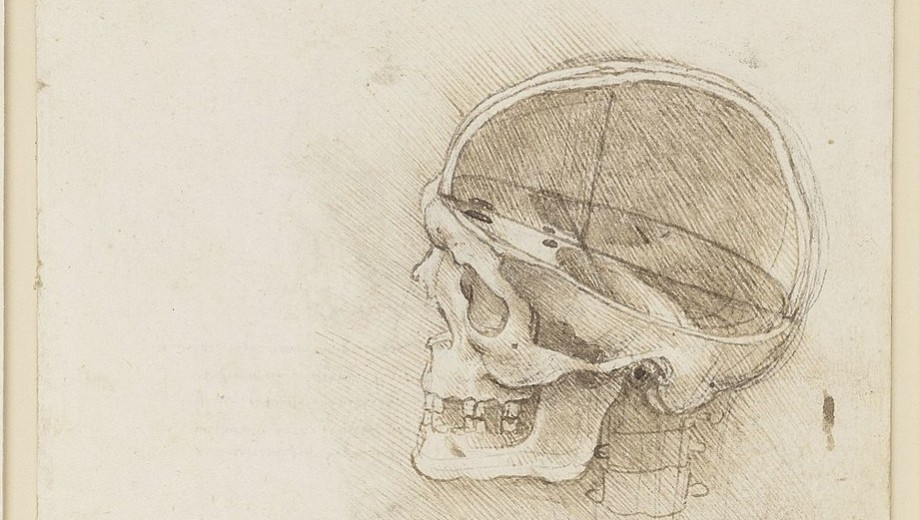

My husband does deep brain stimulation. Several times a week he puts electrodes in people’s brains to look for the places that, for example, a seizure might be coming from. He also did vision research as a fellow at MIT. I was asking him questions about perception, and he said, “Wouldn’t it be cool if we could look at people’s brains while they were looking at art in controlled circumstances?” We started talking with other research teams, and we went to his academic department and said, “There’s very little work being done in this area. Would you support this?” And they said yes.

What was it like to transition to biomedical research?

I had to learn all about how to work with human subjects and collect data. UT Health San Antonio has the Center for Medical Humanities and Ethics. They saw a place for me here—not only to do the brain research but also to be part of a greater intellectual community. There’s research that shows doctors and nurses who appreciate the arts are better at what they do. My husband and I will be coteaching a class in the summer called Beauty and the Brain: Introduction to Neuroaesthetics and Neuro–Art History in the medical school. We’ll be taking case studies through the history of art and examining how sensory perception factors into the ways we can think about those works as they’re experienced by a user in space and time.

Is neuroaesthetics a previously existing field?

Yes. I am critical of the field when it’s done only by neuroscientists, though. It also needs to be done by people who work on aesthetic experience, including art historians and musicologists. It’s about being involved at the ground level of experiment design, where your voice is heard. I love scientists, but they’re not trained in art viewership. A big study came out about the facial characteristics that make a great ruler, based on portraits. It said, “If you want to be a great ruler, this is what your face should look like.” Art historians read it and said, “Yes, except that these ruler portraits conform to a type that has been idealized for thousands of years, and they bear almost no resemblance to what the people actually looked like.”

Barbara Stafford [PhD’72, the William B. Ogden Distinguished Service Professor Emerita of Early Modern to Contemporary Art] wrote a great book and edited a great volume on neuroaesthetics [Echo Objects: The Cognitive Work of Images (2007) and A Field Guide to a New Metafield: Bridging the Humanities-Neurosciences Divide (2011), both University of Chicago Press]. She gave legitimacy to this field along with art historian David Freedberg. Freedberg worked with a research team in Italy looking at macaque brains. Because of the unique situation where my major collaborator is implanting electrodes in people’s brains multiple times a week, we can more easily do this with humans.

Your research piggybacks on scheduled brain procedures?

There’s no brain research where that’s not the case, because there’s no ethics board that will let you just drill holes into someone’s head for fun.

What sticks with you from your UChicago experience?

The sense of warmth in the Art History department, especially because of women like Claudia Brittenham, Christine Mehring, and Persis Berlekamp. Their willingness to talk to me about life and being a mom in grad school was extraordinarily valuable. I had a different background from most of my peers, whose parents were professors, doctors, or lawyers. My dad loaded trucks, and my mom is a nurse. They not only made me feel good about that; they made me feel like the fact that I had worked so hard was always going to be in my favor.

What led you to pursue a PhD in art history?

I went to a very small Jesuit school in my hometown of Jersey City because I went for free. I double-majored in art history and classical studies. I had a panic attack my senior year when I realized that I was a poor kid with a double major in the humanities. What am I going to do, unless Alexander the Great invades New Jersey?

I applied for New York City Teaching Fellows, which is like Teach for America but just for New York City. My GRE score was high in math, which was a crisis area, so I taught math. On the first day of school, I was 22. I had no idea what I was doing. It was a rough school. At the time it was the poorest zip code in America. The population lived in projects in the surrounding areas. However, I loved it, and I did great as a teacher. I learned a lot about myself and a lot about systemic injustice. It changed my life. I’m still in touch with a lot of those students, and I’m really grateful to them.

In pouring my heart and my soul into this work so that these kids could have a good life and fulfill their dreams, I had to ask, “What about my dreams?” I applied to Hunter College for my master’s in art history. I got in, and I got a scholarship. The first year I was teaching full-time and doing my master’s at night—which I had done already, because I already had a master’s in teaching. In my second year at Hunter, I took a leave of absence from teaching to dedicate myself to PhD applications and writing my master’s thesis.

I applied to all the East Coast schools. Then I said, “The school I really want to go to is the University of Chicago—but I’m never going to get in. So let me just apply and throw myself at the feet of Charles Cohen [now the Mary L. Block Professor of Art History Emeritus], whose scholarship I’ve always adored.” And then I got a call very late at night from a man in Chicago, and I knew it was Charlie. I was hyperventilating. That’s how I became an art historian instead of continuing in a career teaching math.