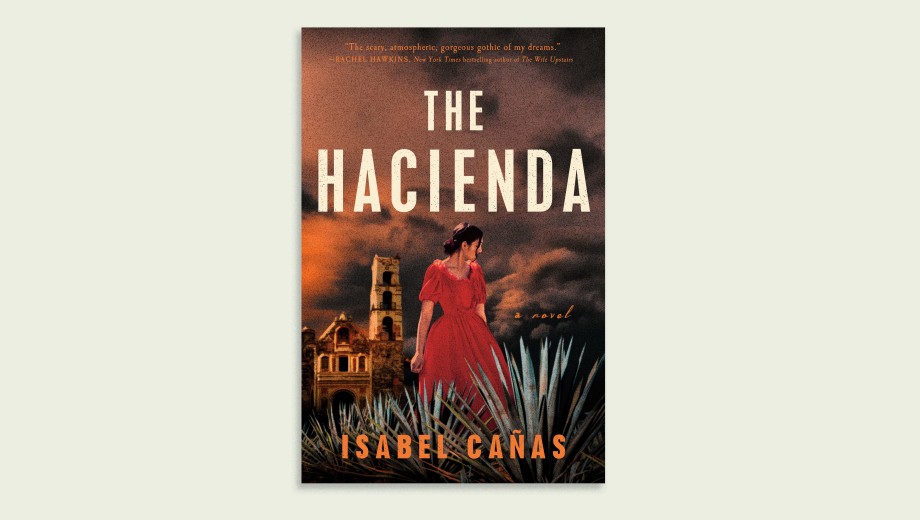

Isabel Lachenauer, PhD’22, drafted five novels while completing her graduate work in Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations. Her debut novel, The Hacienda (Berkley, 2022), a thriller described by the publisher as “Mexican Gothic meets Rebecca,” has received strong reviews in Publishers Weekly and the Washington Post.

Lachenauer, whose pen name is Isabel Cañas, spoke with Tableau about her research, her writing process, and her historian’s guilt about making up things that didn’t happen.

For The Hacienda, you drew on your experience of living in scary houses as a child. What makes a house scary?

One house we lived in when I was five was straight-up haunted: a rickety house from the 1920s in the north suburbs of Chicago, with a really dark, damp basement.

A house doesn’t have to be old to scare you. Another house we lived in, built in the late ’80s, just had vibes that were all wrong.

When I started writing The Hacienda, my husband and I had recently moved to New York, to this corporate apartment with a weird atmosphere. When my husband went away on a business trip, I slept with the lights on. I have a very active imagination.

Your academic work is on Ottoman history and literature. Is there any overlap at all with your creative work?

Zero, even though I frickin’ love Ottoman history. It’s incredibly rich and has such narrative power. Even today those texts have enormous resonance, once you get past the grammar. Ottoman grammar is a bit of a doozy.

Will you ever write anything based in the period you study?

Is this question coming from my adviser? He’s asked me at least four times.

How did you research the period The Hacienda is set in?

At the start of the pandemic, when things were changing so quickly, I realized I needed to go to the Reg and get the sources to finish this book. This was the historian in me. Maybe other people would be busy—I don’t know—packing? That’s actually the last time I was ever in the Reg.

I found this primary source document, a geographical and statistical survey of the region of Tulancingo, now in the Mexican state of Hidalgo, the region where The Hacienda is set. Some bureaucrat in 1825 was sent out from the capital to write descriptions of different areas. How many people live in this town? Where does the water come from? What is the weather like? What kinds of crops grow here? What kinds of livestock live here? What kinds of trees?

I spent my precious last hours in the Reg—when perhaps I should have been doing work for my dissertation—scanning the whole thing. Without it I could not have written this book. If you’re a writer of historical fiction, your jaw—like mine—would’ve hit the ground. Now that I’m drafting my next book, I do not have anything like that, and I am suffering.

You’ve written five complete novels while also doing graduate work. What is your writing practice?

My best writing time is in the morning. I do writing sprints. I’ll set a timer and decide how many words I’m trying to hit. Usually I write for 40 minutes and rest for 20.

Now that I’m a full-time writer, that’s how my days go. I wake up at seven, have coffee, and then I write for four hours. By that point, I usually have 4,000 words.

The best advice that I can give to anybody who wants to pursue a freelance career is to create those rituals and structures for yourself now, because then they become a habit and you have less decision fatigue.

Did your adviser or anyone else know you were writing on the side?

I was so secretive. During the first quarter of my PhD, in one of my very first seminars, a professor assigned us a reading and remarked about the author, “Oh, he doesn’t publish anymore, he writes historical novels.” Very dismissive. At the time I had two documents open on my computer—one for my classes, one for the book I was working on.

In the third year of my PhD, I told my adviser [Hakan Karateke, Professor of Ottoman and Turkish Culture, Language, and Literature] about it. I didn’t know what to expect. But he was so enthusiastic and supportive. I was shocked.

As a historian, do you feel any guilt about making stuff up that might not be historically accurate? Or is it freeing?

That’s something I have so many feelings about. My training is to seek truth. Otherwise why read these texts that nobody else has read for, in my case, 600 years, and that nobody seems to care about? This is my crusade against my own subfield. How dare you not care about these texts?

But I find that with the book I’m working on right now, I over-research. In writing The Hacienda, set in a time and place that I am less knowledgeable about, I was forced to let go and make a few things up. Knowing less actually works in the storyteller’s favor, to some degree.

When I write a first draft, I often have so many brackets in the text: Look up what kinds of trees grow here later. Look up what kind of food they’d be eating here. If you don’t, it’s easy to get bogged down. My craft as a historian is separate from my craft as a writer.

My next novel, which has not yet been announced, is fantasy. Writing fantasy is a breath of fresh air, because I’m not having that internal battle about where I’m allowed to break the rules. The rules have been a part of my life for a very long time. And they’re good rules. They’re just tools for a different career.