An advanced degree in ethnomusicology sounds enticing: not every discipline accepts an evening at a nightclub as research. But consider some of the requirements of the PhD at UChicago: a reading knowledge of three languages, sight-reading and singing exams, a public recital, not to mention two-plus years of course work, comprehensive exams, and a dissertation proposal and defense.

Ethnomusicology is defined as the study of social and cultural aspects of music and dance in local and global contexts; it combines training and approaches from music and anthropology. The rigorous well roundedness of UChicago’s ethnomusicology graduate program—offered in the Department of Music—helps to make it distinctive, says Philip Bohlman, the Mary Werkman Distinguished Service Professor in Music. “It might not be obvious to an ethnomusicologist studying Indian music why he or she needs to learn how to play piano,” Bohlman says, but in the end, students frequently tell him, “I’m so happy I had to learn these things in such a fundamental way.”

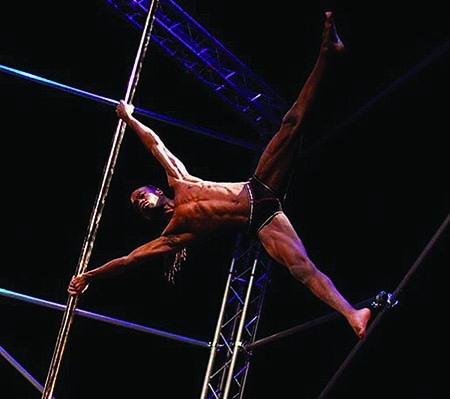

Student Alisha Lola Jones is working on a dissertation about the role of black men’s gender and sexuality in gospel-music performance in Chicago and Washington, DC. She says the program’s challenging comprehensive exams exposed her to “great theoretical tools that can inform my analysis of areas like cinema theory,

Christian mysticism, and men’s studies.” She’s interviewed self-identified straight and same-gender loving black men in the ministry as well as an artist whose YouTube videos show him gracefully pole dancing to gospel music as a form of worship.

Michael Figueroa says he found the performance requirement more emotionally taxing than exams. In his fourth year, he gave a guitar recital knowing that “the department wants us to be active in music making in addition to thinking and writing about it.” Figueroa is writing his dissertation on music and violence in the Middle East, examining “the idea that songs can drive people to political action.” His field research in Jerusalem—an experience he describes as a “brain rush nearly every day”—included a four-hour interview with Dan Almagor, a songwriter and playwright whom Figueroa describes as “one of the busiest people in Israel.”

The way Figueroa sees it, ethnomusicology, “a little-known but long-named discipline,” trains people to think in “a critically cosmopolitan way. We learn about the lives of others through music.” In ethnomusicology, students learn from living people as much as static sources: “I spent a lot of time in the archives at the National Library of Israel, but ethnography is really central to our approach of studying music.”

Men have had a lot to say about women and their bodies. Why can't I return the favor? —Alisha Lola Jones

Ethnomusicologists frequently find unusual points of entry. Figueroa, who is of Puerto Rican and Syrian descent, came to his subject by taking a popular Modern Hebrew class with senior lecturer Ariela Finkelstein, AM’96, “on a fluke.” By contrast, Jones, a former beauty-queen-cum-minister, entered the program after graduating from Yale Divinity School. “I originally didn’t want to be the stereotypical black girl doing gospel music,” she says, and hoped instead to build on her previous training in Western art music and international folk music. She changed her mind when she found a topic that “would allow me to research social issues that I encounter as a public theologian who leads worship.”

To further define her research, Jones is striving to make her dissertation “fun and contemporary” and to study “untapped issues” in the Pentecostal church such as gender roles in black worship experiences, the implications of HIV/AIDs discourse, homosocial  networks, and “interpretations about what it means to be a gospel performer.”

networks, and “interpretations about what it means to be a gospel performer.”

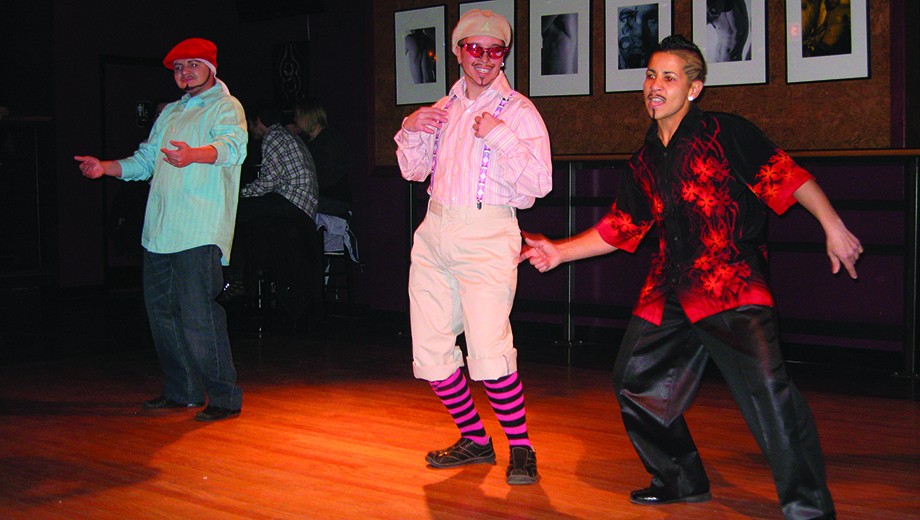

Both Jones and Figueroa studied music as undergraduates; meanwhile, Adrienne Alton-Gust, AM’06, began college as an engineering major. Although she eventually turned to music, she says, “I didn’t come in knowing I’d be working with drag queens.” Her dissertation explores the role of music in drag performance. She calls ethnomusicologists “social scientists among music scholars.”

Alton-Gust’s line of study embodies a theme—the relevance of popular music—that has come up repeatedly in the 25-plus years since Bohlman landed the University’s first appointment in ethnomusicology. “My early teaching didn’t use a lot of popular music,” says Bohlman, “but I’ve learned from my students that this is an important aspect of the vitality of diverse music in the world.”

One graduate student who immersed himself in popular music is Will Faber, whose dissertation is on black music in Britain, particularly jazz and electronic dance music. He spent time in London shadowing sound engineers in clubs, interviewing musicians, and poring over the archives at the city’s Musicians’ Collective. Now, he says, “Musicians I’ve worked with in London will pass through Chicago, and I’ll go to Smart Bar and listen.” Just because an ethnomusicologist has left the period of what Faber calls “research-research” doesn’t mean “that you can’t have encounters that force you to rethink it.”

The social aspect of ethnomusicology research isn’t always a perk. While Alton-Gust’s friends sometimes ask to tag along on her research outings “because it seems like so much fun,” she admits that late-night bars and clubs are “not always the safest places to work.” She’s observed bar fights and patrons being abusive to performers. Jones, meanwhile, has encountered some resistance from church leaders when she discusses her research. “Men’s sexuality is a really contentious topic” in the Pentecostal church, she says. “I’ve been informed that only men should research men. But the way I see it, men have had a lot to say about women and their bodies. Why can’t I return the favor?”

Many students in ethnomusicology find that their research enriches more than their academic lives. “I feel very privileged to have had relationships with the same musicians for over ten years now, to be able to ask these questions in a supportive community,” says Faber. He also admits that one benefit of his London research was “going out dancing with my wife,” and it’s hard to deny that graduate students in the department are enjoying their work. “Ethnomusicology really facilitates living a good life,” says Figueroa. “It changes the way you travel and think about everyday situations and encourages you to think critically about your place in the world.”

Add new comment