With minimal rehearsal time and a sparsely set stage, three UChicago graduate student performers—Jacob Reed from Music and Elena Rose Light and Clara Nizard, who are both pursuing joint PhDs in English Language and Literature and Theater and Performance Studies (TAPS)—contributed to a lively and playful production of John Cage’s opera Europera 5 at the Reva and David Logan Center for the Arts in May. The performance was the culmination of the 2025 Berlin Family Lectures, featuring world-renowned opera director Yuval Sharon.

“Cage did not want the piece to be overly rehearsed,” Sharon explains, “because he wanted performers to avoid getting too comfortable. It was meant to feel ‘on a knife’s edge,’ spontaneous and rehearsed just enough, requiring total concentration and commitment.”

The performance also required a willingness to experiment. Like the other operas in Cage’s Europera series, composed at the end of his long, provocative career, Europera 5 has no plot. It does not unfold according to a conventional operatic score, nor does it sound like a conventional opera.

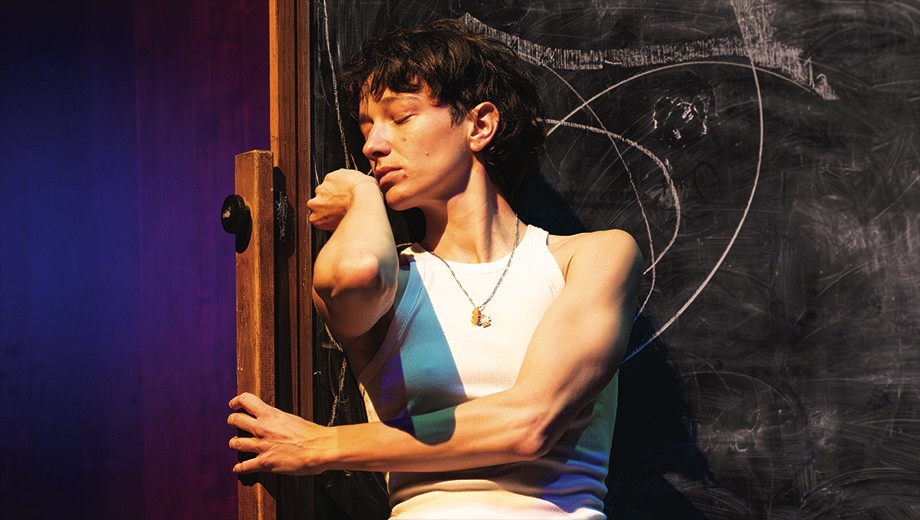

Instead, two singers and a pianist each perform different arias—selected from the entire canon of European opera—during a precisely timed 60-minute work. Their entrances, the entrances of dancers Light and Nizard, and sound from nonhuman sources such as a radio and a record player were all determined by chance and notated in an ephemeral score created fresh for the performance.

For pianist Reed, this meant an unaccustomed commitment to not listen to the vocalists when they performed music that diverged from his own. Additionally, he had to play three of his six pieces as normal while only “shadow playing” the others. This was a technical challenge that required figuring out how to perform the music without depressing the piano keys—though a random, accidental key strike would have been a welcome addition to the chance array of sound.

Reed put a great deal of thought into his choices of works, deciding on three selections from recognizable warhorse operas for the audible performances and three more esoteric selections for the unsounded shadow play. Because Cage had described the Europera project as a way of “sending opera back” to Europe—by creating a novel, American approach to opera that draws playfully on the genre’s long European tradition—Reed liked the idea that his shadow play choices were European operas set in imagined American settings, such as Puccini’s La fanciulla del West (The Girl of the Golden West).

When he first met with Sharon, Reed was interested to see what the director would make of his careful choices. “I was expecting him to offer more input,” Reed remarks, “but he just said, ‘Yeah, those will sound great.’”

Sharon was not uninterested in Reed’s choices but was attempting to follow in the composer’s footsteps by enacting what he termed “light leadership” as opposed to the all-powerful role directors tend to play in the opera house. Similarly, Cage had tried to disrupt a perceived hierarchy in which composers dominate, their expressive intentions shaping the performers’ actions and the audience’s experience of their work. By choosing the parameters of a piece through chance procedures, such as rolling dice or consulting the I Ching, Cage had attempted to downplay his own intentions while compelling performers’ and listeners’ active attention to sounds—musical or otherwise— that surrounded them.

Cage’s title emphasizes this as well as its reply to European opera. It can be heard as “your opera,” an opera in which performers and audience members are invited to choose how to interact with its various components on a spacious set that allows them to decide where to focus their attention.

The dancers, whom Sharon had added to the cast, improvised their movements within the vast near emptiness of the performance space. Apart from a grid marked on the floor, the stage was dominated by a digital clock counting down the performance’s run time. Grouped together against the back wall, a few pieces of furniture suggested the living room of a comfortable home—an upright piano, a radio, a rotary telephone, and an armchair cozied up to a record player on a cabinet replete with a drawer full of records. Just above the clock at center stage, an image of an old-fashioned television set presided over everything, its screen variously presenting a baseball game, a tennis match, and two recorded opera productions.

As the dancers entered at different places along the grid—often carrying items claimed from the TAPS prop shop to play with as they interacted with the other performers—they also had to watch the clock surreptitiously.

“Just on a performance level, you don’t want to look like you’re looking at the clock,” says Light. It was “like bureaucratic labor while doing the performance labor. We had these little sheets of paper with our score,” along with extra clocks backstage to help keep track of when they were scheduled to appear.

Titled “Anarchy at the Opera,” Sharon’s Berlin Family Lecture series, delivered over three weeks in May, argued for reimagining opera through the lens of anarchism. He defined the term loosely, flirting with stereotypical imagery of bomb-throwing—and potentially opera house–burning—political radicals while also drawing on the work of historical figures, such as philosopher and economist Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, and more contemporary scholars, such as David Graeber, AM’87, PhD’96, and David Wengrow, to ground his reading of anarchists as egalitarians who, perhaps like Cage, prioritize “horizontal” over hierarchical relationships.

The audience seemed to enjoy playing along, making the opera theirs through an unusual level of interaction. During one vocalist’s aria, in the middle of a great deal of other action, the singer chose to bow as though receiving applause at the end of a performance. Noting the familiar gesture despite its unfamiliar place in the performance, a group of audience members began to clap. The vocalist continued to bow as he sang the rest of his aria. And they continued to clap each time he did so, their own performance having become a part of the action.

“People wouldn’t feel the agency to engage without some level of social script in place,” marvels Light, remembering the unexpected reaction. “Anarchy at the opera is just the right amount of safety, actually, and just the right amount of knowing what you can do and cannot do.”