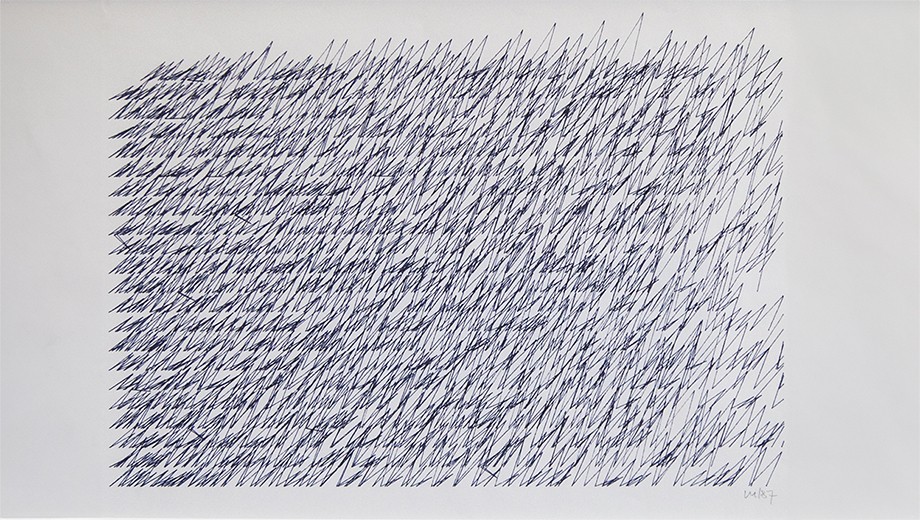

Zsofi Valyi-Nagy, AB’13, AM’18, PhD’23, has long had an affinity for what she calls the “creative misuse” of technology, that is, “artists experimenting with technology that they maybe don’t fully understand and using it for something that it wasn’t intended for initially.” A specialist in new media art and a visual artist herself, Valyi-Nagy has spent the last several years researching Vera Molnar, who is best known for her plotter drawings made on computers beginning in the 1960s. Using programming languages that weren’t necessarily intended to create images, Molnar programmed these early computers to draw for her, using a mechanical arm, or pen plotter, to ink lines along x and y axes.

Though Molnar, who died in December 2023, is regularly called a pioneer of computer art for this experimental work, she preferred to be known as a painter. At first this choice puzzled Valyi-Nagy, but as she learned more about how the artist worked, she came to appreciate how Molnar integrated computers into her drawing and painting practice. For her it was never simply a matter of entering code into a machine.

Art historians may sometimes emphasize the final art object over the work that went into it, but Valyi-Nagy saw that with digital art—and with Molnar’s work in particular—it was essential to shift the focus to the artistic process. “When early computer graphics are exhibited in museums,” she says, “what you’re not seeing is the really complex iterative process that led to that image. There was this misconception, maybe, when you just see the framed hard copy, that there was an algorithm that was written, you press Go, and then it was output to paper, and that was it. And so the question is, What is the art? Is it the code, or is it the picture? And I find that binary not very productive when it comes to Molnar’s work, because there’s so much in between the code and the output that you don’t necessarily see.”

In addition to studying Molnar’s archives, Valyi-Nagy tracked down early computers and recreated Molnar’s work—an approach called media archaeology—and conducted extensive interviews with the artist. Valyi-Nagy found the prospect of these interviews daunting at first, and learned that other graduate students in her department researching living artists faced a similar challenge. Together they started the workshop series Speaking of Art: Artist Interviews in Scholarship and Practice to learn how to incorporate oral history into their research.

Through conversations with Molnar and archival research, it became clear that the artist’s process “was very much not linear,” says Valyi-Nagy, and that her work with computers was completely integrated into her studio practice. Though Molnar is best known for her earliest plotter drawings (“Art history is all about, Who did this first?” says Valyi-Nagy), the artist’s work from the 1980s interests Valyi-Nagy even more. In the 1960s, Molnar worked in a computer lab away from her studio, on a computer without a screen. After she programmed it, she had to wait hours—sometimes days—to see the resulting plotter drawing, make changes to the code, and generate a new drawing. By the 1970s she could interact with her drawings on a screen; by the 1980s, she had a computer in her studio. Suddenly “she was moving back and forth between analog images and digital images. She was sketching in her notebook, turning that into code, which would transform into this digital image that she would then transform again and then output to the plotter.” (Valyi-Nagy even found photographs Molnar had taken of her computer screen throughout the 1970s, the existence of which raises more questions about Molnar’s relationship to the computer: “Why did she take a picture of the screen when she could output it to paper?” Valyi-Nagy wonders.) Molnar’s geometric drawings are deceptively simple, she realized. Molnar was engaged in a conversation with the computer; rather than accepting its output as the last word, she found different ways to reassert her artistic hand.

In combining analog and digital media, Molnar also participated in the debate—already top of mind when she began working on computers—over whether humans would be replaced by the new technology. “She had this way of programming the computer to almost simulate human error, like using randomness to create a tremor in the plotter-drawn line. Or she would draw a concentric square series with a computer, but then add in her own hand-drawn lines and ask you to question, Which one of these is better than the other?” Valyi-Nagy emphasizes the humor in Molnar’s approach: “There is a sort of playfulness to this where she, I think, maybe thought that this entire debate was ridiculous and silly. And she’s like, of course, the computer is not going to replace the artist. And also, behind every program there is a person.”

For years early computer artists like Molnar have not been taken seriously, explains Christine Mehring, the Mary L. Block Professor of Art History, who was Valyi-Nagy’s dissertation adviser. Not only was their work seen as “geeky,” she says, but there was also a misconception that in computer art, “the artist has a decreased importance as an individual creator.” With the emergence of sophisticated generative technologies over the last few years, these artists’ early explorations of the relationship between artist and computer have become more relevant than ever.

Mehring’s hope is that as more people learn about artists like Molnar, “we’ll have the resources and the time and the expertise to think about how to preserve this kind of art within museum collections,” as well as the machines on which the art was made. “I think we’re just at the beginning of how important this prehistory of computational art will be,” says Mehring.

In her own artistic practice, Valyi-Nagy probes the possibilities of technology in art. Like many people who grew up at the dawn of the internet age, Valyi-Nagy explored the creative potential of computers and the internet when she was younger, making bitmaps (pixel drawings) and sharing them via GeoCities, which hosted user-created websites. She continues to incorporate a mix of technologies into her artistic work today, “investigating where these technologies fail—or fail to do things that I want them to do.” Searching for what tools like 3D scanners, holograms, or X-rays are unable to capture, she highlights those glitches and holes throughout her work, drawing attention to the limitations of these technologies.

While in graduate school, Valyi-Nagy began experiencing severe chronic pain. As her doctors struggled to find a diagnosis, she says, “I became really interested in the role of imagery in diagnosis, and how I was getting all these X-rays and MRIs, and nothing was showing up, but I felt so much pain and it seemed like the doctors wouldn’t believe me.” The experience got her thinking about a question that has long been part of the conversation around media like photography and holography: “that something has to be visible in order to be true.” To explore this tension, she created what she calls “AI-assisted collages,” feeding assemblages of diagnostic images and paint through an AI program, adding a randomness that she feels is in keeping with Molnar’s work. She has experimented, too, with text-to-image generators, honing the language she uses to prompt the AI through an iterative process like Molnar’s. The AI often comes up with something completely unlike what she imagined. “It’s always some sort of collaboration between you and the technology.”