Spanning from the medieval to the contemporary—and from the Americas to North Africa, Iberia, and France—the scholarship of the Romance Languages and Literatures junior faculty is “grounded in close attention to literary and cultural objects,” notes department chair Alison James, “while engaging with interdisciplinary fields of broad humanistic significance, including environmental criticism, gender and sexuality studies, theater and performance studies, and postcolonial studies.” Tableau spoke with four of the department’s assistant professors about their work.

Medieval machinations

“Through technology you can unlock a potential that you could not access naturally,” says Noel Blanco Mourelle, a specialist in medieval and early modern Iberia. He shares his subjects’ fascination with “technology that seems slightly crazy.”

Blanco Mourelle’s first book project centers on fourteenth-century theologian and philosopher Ramón Llull’s ambition to create a universal language that could “prove to people of other faiths that Christianity was logical,” he says. The Art, as Llull called his ambitious work, went beyond a philosophical treatise. It was a whole system relying on “wheels and machines and diagrams,” including a wheel featuring concentric circles of parchment pinned in the center so they could spin freely. Letters that stood for words were written around the circles, and as one turned the circles, aligning the letters in different ways, the corresponding words would “create what he felt were perfect arguments,” Blanco Mourelle explains.

He also studies how others modified Llull’s work over the centuries. One educator turned Llull’s wheels into tools to teach Latin grammar to the daughters of King Philip II of Spain in the sixteenth century.

Blanco Mourelle notes that a challenge when researching and teaching this material is the enmeshing of religion and science in medieval Europe, when goals of conversion often underpinned scientific thinking. For instance, Llull lived on the island of Majorca, today part of Spain, which had gone through a period of Islamic rule in prior centuries. “You don’t want to transform this into a completely secular story,” Blanco Mourelle says. “It’s a complicated thing to unpack.”

The limits of nature

Research topics like waste and menstruation might surprise a newcomer to early modern French literature, but Pauline Goul explains that they follow quite naturally from the era she studies. In the sixteenth century, authors like Rabelais and Montaigne were preoccupied with excess and bodily functions; as she says, “I end up working on these texts that just have no shame about these things.” And she wondered what those excesses might have to do with environmental concerns.

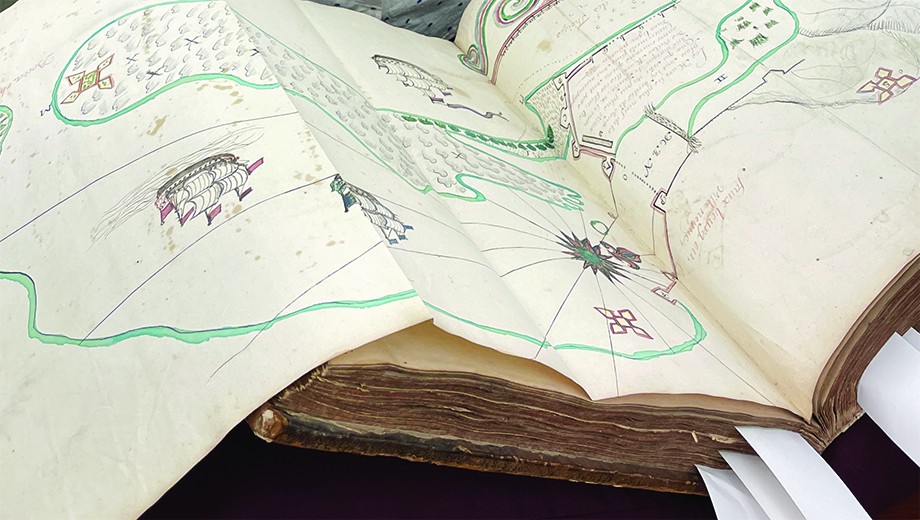

Goul’s first book project grew out of a broad consideration of waste and sustainability in this period of colonial conquest and extraction. She acknowledges that “sustainability” in the way we understand it today was not a concern back then. Yet at that moment, when maps reflected a view of the New World as “resources that could be exploited,” Goul explains, early modern authors laid the groundwork for our modern use of the term by beginning to ask questions that preoccupy us today: “What are excessive appetites? Can we go on in this way forever, or are there limits?”

Recently she has also worked on the connection between women and nature in early modern French literature. One text she examines is an agricultural treatise that describes certain plants used to regulate menstruation or terminate pregnancies. At a time when there was much anxiety about the “inscrutability of the female body,” Goul says, women’s engagement with nature opened up space for bodily autonomy, sexuality, and intimacy among women.

Decolonizing literature

A specialist in francophone North African literature, Khalid Lyamlahy studies the generation of Moroccan writers who began their careers with the journal Souffles. He says the publication, founded in 1966, was a forum for debating postindependence questions: “How do we decolonize our culture? How do we build a new cultural identity that is free from both colonialism and from the traditional patriarchal structures of society?” Souffles contributors also grappled with whether and how they could “still write in French, the language of the former colonizer,” he adds.

Lyamlahy focuses on how three authors associated with Souffles—Abdellatif Laâbi, poet and editor in chief of the journal; sociologist, writer, and critic Abdelkébir Khatibi; and Amazigh poet Mohammed Khaïr-Eddine—incorporate subversive and nostalgic modes in their writing.

A creative writer himself, Lyamlahy has published two novels. The first, Un roman étranger (A foreign novel) (Présence Africaine, 2017), draws upon his own frustration navigating bureaucracy as an immigrant to France. The second, Évocation d’un mémorial à Venise (Evocation of a memorial in Venice) (Présence Africaine, 2023), which received special mention from the jury of the prestigious Prix des cinq continents de la Francophonie in March, is an attempt to process the tragic death of a Gambian refugee who drowned in Venice’s Grand Canal in 2017 with bystanders watching him—even insulting him. Writing novels and book reviews is important to Lyamlahy, he says, because it “allows you to be in conversation with a broader audience.”

He has also translated literature, publishing an Arabic edition of Senegalese author Felwine Sarr’s Habiter le monde: Essai de politique relationnelle (Inhabit the world: Essay of relational politics) in 2022 (Kulte Editions). Though he has ventured into self-translation, publishing short excerpts in English from his first novel, Lyamlahy has no further plans to translate his own writing: “It’s far better when someone else translates your work, because it gives the work the opportunity to come out as something new.”

Beyond minstrelsy

When people hear the word “blackface,” they may think of the nineteenth- and early twentieth-century tradition of minstrelsy in the United States. But blackface is “all over the Americas,” says Danielle Roper, Neubauer Family Assistant Professor in Latin American Literature. “Racial caricature is something that representations of Blackness in popular culture are constantly mediating.” Roper is interested in all the places blackface performance crops up today, whether in a dance group’s depiction of slavery at an Andean fiesta in Peru, in Jamaican popular theater, or in a Spanish-language television show in Miami.

The existing framework of the US minstrel show is inadequate for understanding such diverse forms of racial impersonation, Roper says, and there are limits to thinking about blackface within any one nation. She explains that blackface is “a shared phenomenon that comes out of a history of slavery,” and if scholars consider its practice across cultures, “we might better be able to wrestle with what it is that blackface enables people to do. Blackface performance is a way of fixing or reiterating dynamics of racial power in a contemporary moment that’s defined by change, as these countries transition from discourses of color blindness to ones of multiculturalism.” She suggests that blackface performance operates in relation to myths of racial democracy—nationalist discourses that deem the “race problem” foreign to the nation.

Roper also does curatorial work related to visual interpretations of the legacy of slavery. Recently she curated the virtual exhibition Visualizing/Performing Blackness in the Afterlives of Slavery: A Caribbean Archive—part of a digital initiative created by UChicago’s Working Group on Slavery and Visual Culture—which features contemporary Black artists from the Caribbean. Roper says the exhibition asks, “How do Black artists today wrestle with visual idioms from slavery in a particular moment that is defined by racial reckoning?”