Edgar Garcia is an associate professor in English Language and Literature and Creative Writing. His most recent book, Emergency: Reading the Popol Vuh in a Time of Crisis (University of Chicago Press, 2022), examines the K’iche’ Mayan creation story through a collection of essays.

My newest book takes on questions of time and change directly. The book is titled Emergency because it sees the time of the writing of the Popol Vuh as just that—a time of emergency, of crisis. The Popol Vuh was put to paper in 1702 by a Dominican friar to be included in a four-part manual on converting the Indigenous people of Guatemala. Colonialism was in action. But, as I say, this book is also a creation story communicated to that friar by Maya scholars and elders. In making their world-creation out of colonialism, they show us how world emergence is tangled with emergency, creativity with crisis.

In those moments, time both collapses and restarts. It feels both impossibly long and terribly sudden. While the experiences of the past years in the pandemic could never compare with the 90 percent population loss due to [non-native] diseases and the violence of colonialism, I do feel in the pandemic we got some sense of how the time of crisis collapses, suspends itself, prolongs a sense of being extratemporal, and then restarts in difficult, recursive shifts.

In the most straightforward terms, Emergency came from the pandemic—from being stuck at home with what I had in March of 2020. I had just taught a class on the Popol Vuh, and I had all the books at my house. And I started to think with them about my world. My world felt both impossibly contingent in contemporary crisis and deeply captive to longer histories of colonialism, social and environmental crises, and world creation in the Americas.

What is unique to me about the Popol Vuh is that it is a story of creation that doesn’t make its world out of primordial darkness, but out of historical darkness—out of the crisis of colonialism. It begins: Here in Christendom, in the time of the teaching of Christ, we will bring light out of the eastern sky. We will bring the sun into existence. That’s a different kind of creation story from one that begins in cosmic Nothing.

One idea such world creation in historical crisis prompts is that people are always relearning: that there is not only progressive accumulative knowledge, but also people looping back to their errors—looping back to shortcomings, looping back to inabilities—and that this is, in the end, a beneficial thing. Creation is editing. Creation is revision. Creation is history.

That said, I don’t want to overstate the case that it’s about a very particular moment in history: a moment of severe crisis. I found that move from such devastation to world articulation really inspiring. And sometimes works of literature do that because they don’t happen in mechanical, quantifiable time. They happen in the experiential time of song, memory, and desire.

I called it Emergency because within emergency is the word emergent. So much of the book’s spirit—its critical reflection—comes out of an idea that there are no possibilities without problems. There is no creativity without crisis. There is no world emergence without world-historical emergencies.

Thomas Pashby is an assistant professor in Philosophy. He specializes in philosophy of physics—especially the interaction of physics, metaphysics, and the philosophy of science.

The way I approach a philosophical question I’m interested in is to look at the science that seems relevant, then see if we can make any progress on the philosophical question by thinking about the science.

Time is an interesting topic, because for me we’re really asking about our experience of time and how that experience gets represented in physics. I follow Donald Williams in regarding our experience of the passage of time as watching events move from the future into the present to the past. Our experience of time, then, is local—we experience the events that happen around us but not distant events.

I’m writing a book on the history of time in physics called “Time from Aristotle to Einstein.” Aristotle makes an assumption that amounts to the existence of a shared present, of successive universal nows. It’s an assumption that everyone before Einstein was prone to make when thinking about time.

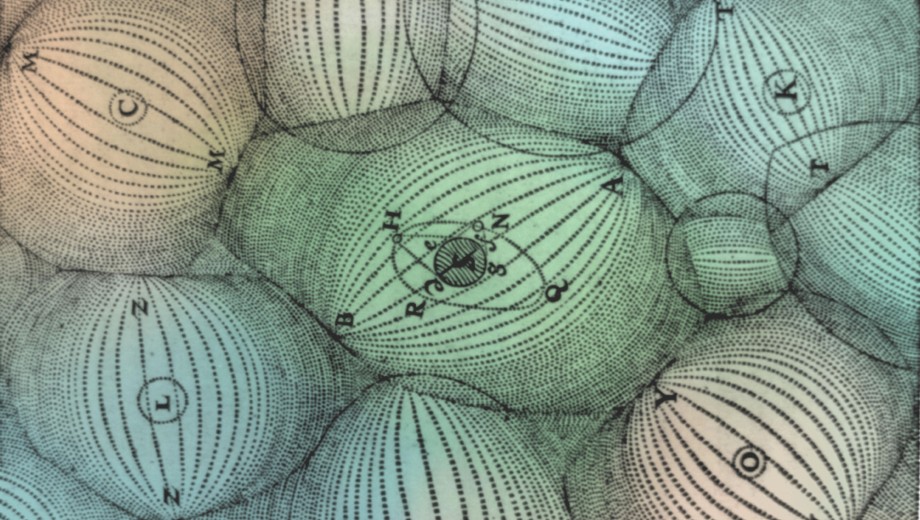

Then came Einstein’s special relativity, which has no universal present. In this way of thinking, sometimes called many-fingered time by physicists, each observer in the universe has their own notion of time, as if they were carrying their own personal watch that tells the time for them alone. We learned that rather than one global structure of time that we experience together, we experience different aspects of a universal structure that looks different depending on where you are in space-time.

One of the debates in the less physics-y philosophy of time is about how our theory of time should deal with tense: past, future, and present. It became the central question in analytic philosophy of time in the early twentieth century: Is tense a real feature of the world, or can tense be reduced to mere events and relations, so that we don’t have to worry about the changing of events from future to present to past? I’m currently developing a tensed theory of many-fingered time for relativistic physics.

What’s this knowledge good for? Well, physics tells us there are certain effects involving these differences in observers’ notions of time that we’d better account for. For example, each GPS satellite needs to have its clock compensated for its motion through Earth’s gravitational field. If they didn’t compensate for these general relativistic effects, then the whole system wouldn’t work and the GPS receiver in your phone would report the wrong position. Another example is in accounting for the lifetimes of excited particles: cosmic rays coming into the atmosphere that could be coming from different galaxies or from the very early universe. Two particles of the same type—say two positrons or two muons—have the same characteristic lifetime, but because of this relativistic effect (time dilation), the faster they move relative to us, the longer they seem to live. As if each particle kept its own personal time.

But the idea that there’s something mistaken about the view that you and I share a universal present is interesting and meaningful in its own right. It encourages a relationist perspective, where what we experience as physical objects in the world are these local interactions—mostly with light, with the electromagnetic field. I find the idea that we have a global order emerging from local physics very interesting, and—for me—this takes us right to the very base of reality.