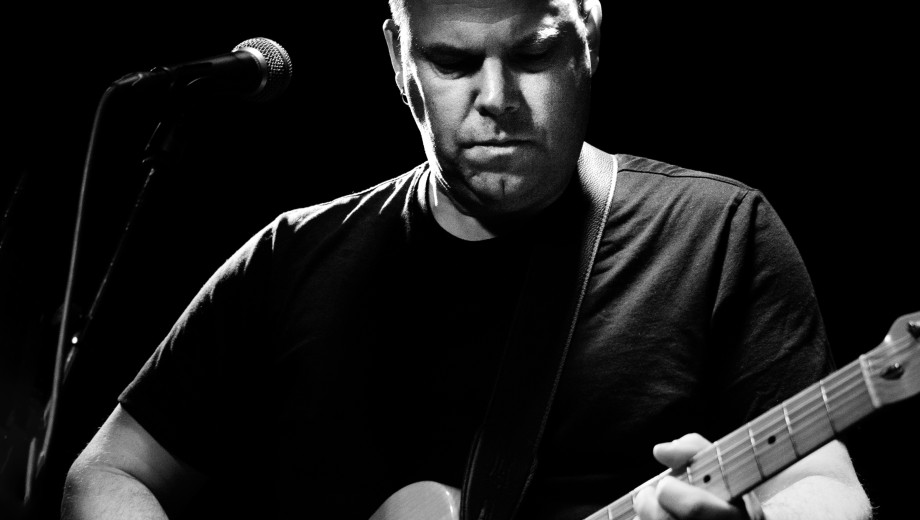

English Language and Literature alumnus David Grubbs, AM’91, PhD’05, is a professor of music at Brooklyn College and the CUNY Graduate Center, as well as a prolific experimental musician and multimedia collaborator. At Brooklyn College, he teaches in three MFA programs: Performance and Interactive Media Arts (PIMA), an interdisciplinary program he codirects; Sonic Arts, which focuses on composition and sound design; and Creative Writing. Grubbs’s latest solo album is Creep Mission (Drag City, 2017), and his latest book—a long-form poetic reflection on life as a touring musician—is Good Night the Pleasure Was Ours (Duke University Press, 2022).

You got your start in the punk scene in Louisville, Kentucky. What was that like?

Louisville had a kind of quirky, interesting history of punk and post-punk bands coming from the Louisville School of Art. It already had its own eccentric, distinctive character by the time I picked up on what was going on, maybe when I was a sophomore in high school. My sense of playing in a punk band was that it was our opportunity to intervene. What we were doing seemed not only fun, but particularly relevant. One wasn’t waiting for one’s time to be older and be taken seriously. That time was now—even if you were only 14 years old.

Your bands were increasingly experimental over time. Did you always have that impulse as an artist?

For me, a decisive shift happened in the early 1990s. I moved to Chicago in 1990 to start a master’s at the University of Chicago. That was the moment my band Bastro, which had been a noisy post-punk power trio, morphed into Gastr del Sol. And I also began playing with a group called the Red Krayola. The Red Krayola started in Houston, Texas, in 1966—I was born in 1967, so they have been around longer than I have—and had a revolving door of participants. Suddenly, I was operating outside of the rules of being in a band that had a fixed membership and a regular rehearsal space. Gastr del Sol quickly became open to different constellations of players for different recordings and different concerts and different tours. It allowed me to collaborate much more quickly with a wider group of people. And I just learned a hell of a lot more. I was eager to step outside of familiar surroundings and play with people with different musical backgrounds. For example, at that moment I first played with Mats Gustafsson, who comes from a free jazz background and was a favorite and regular of the improvised music scene in Chicago.

In these bands I’ve played in, I wouldn’t want to overstate my own agency. It really has to do with what emerges among the participants. I’ve been thinking about this a lot because I’ve just started work on a next book, which is about working collaboratively.

Did you come to Chicago for grad school or music or both?

It was a convenient combination of the two. I already had a lot of friends through the music scene. Squirrel Bait, the band I was in in high school, had played in Chicago—with the bass player’s mother driving us up. And I wanted to work toward a PhD in English. I imagined myself being a college professor. I couldn’t imagine in the long term being able to survive just playing music, and that’s still kind of the case.

Do you think of your academic work and your musical career as separate?

For years I imagined them as completely separate. I never studied music in college or in graduate school. I’ve been a music professor now for 17 years, so there’s been a fair bit of time for on-the-job training. But I really kept the two separate—and perhaps too separate, because it’s been extremely rewarding to feel the two practices merging.

I’m really fortunate with the position that I have. I was hired at Brooklyn College as part of a new Performance and Interactive Media Arts graduate program as the music and sound person but with the thought that I would be conversant in contemporary art, performance, theater, etcetera. Coming into teaching in an explicitly interdisciplinary position really worked. If I’d been hired into a very traditional music department or a traditional conservatory, that would’ve been a rough transition.

What is teaching like for you?

I primarily teach graduate courses. There are usually 10 or fewer people in my seminars. Today I’m giving feedback on final MFA thesis essays—essays accompanying capstone performances in the PIMA program. I’m able to work very closely with students and mentor them. The program is interesting in that all of the student work is done collaboratively. So the final thesis performances are collaborative groups of usually two to four people.

As a teacher, I always try to draw on the example of Miriam Hansen [1949–2011; formerly the Ferdinand Schevill Distinguished Service Professor in the Humanities, Cinema and Media Studies, and English Language and Literature]. I was very interested in writing about the culture of sound recordings on the basis of readings that we had done in her seminars from Adorno and Benjamin and Siegfried Kracauer. In addition to being a brilliant scholar, she was such a great teacher in having us walk through these very difficult theoretical texts paragraph by paragraph. I was so accustomed, particularly in my undergraduate days, to people shooting from the hip. I graduated from college in 1989 when poststructuralism could be used as a kind of cudgel for some people to dominate the discussions. Miriam Hansen would not stand for that. She was so rigorous and thorough, but also generous and generative and super interested in close group readings of the texts. That’s something I think about frequently in my own teaching.

What else stands out to you from your UChicago experience?

Working as an editorial assistant at Critical Inquiry. I’d taken a couple of classes with [longtime Critical Inquiry editor] W. J. T. Mitchell, and he wound up being one of my dissertation advisers. The job was primarily proofreading but also fact-checking sources. I would frequently take the cart from the office to the library and check out 50 or 60 books—that would be all of the footnotes in an essay by Hortense Spillers or Derrida or you name it—and go through and check every quotation and every source. Just reading those essays very closely, discussing them in the office—what an amazing job.

Also, Critical Inquiry was always bringing extraordinary people to campus. Should I tell you about how I feared that I’d poisoned all of the people who attended a lecture?

Yes.

I think it was a Rosalind Krauss lecture. Tom Mitchell said something like, “I’m tired of the usual wine and cheese at these receptions. We should do something exceptional like sushi.” I’m from Kentucky. I’d never seen sushi before. And at that time there was only one Japanese restaurant in Hyde Park. They were open for lunch from like 12 till 2, and the lecture was at 5 p.m. So I picked up all the sushi at 1:30—almost a station wagon full of sushi. I said something like, “It’s okay to refrigerate this, right?” And they were like, “No, no, no. Do not refrigerate the sushi!” I said people won’t be eating this for like four or five hours. And they were like, “No, no, no, don’t do that either!”

So I took the sushi and decided to put it in the refrigerator for an hour and then take it out—I mean, there was no internet for me to check. I dealt with my nervousness by laying it out in these elaborate patterns on long tables. Then I thought, if people are going to get poisoned from this, I should eat some first so I can warn people. So that’s when I first had sushi. And as far as I know, no one died of food poisoning.

You moved to New York City before graduating. Why?

I was in Chicago from 1990 to 1999—in the nineties, precisely. In addition to the University of Chicago being a great place to study literature, living in Chicago was an ideal balance for me of playing music and being in school in a large international city where, at least at the time, musicians and artists could live rather cheaply. I plowed ahead and did my coursework for the master’s and the PhD and comprehensive exams and language exams and all that stuff in a timely fashion, and then I just got wrapped up playing with Gastr del Sol and the Red Krayola. I moved to New York in 1999 and did music full-time for six years. Moving was a bit of a shock. I knew all of these musicians and artists who lived in New York City, but then I learned that most of them were on tour for six months a year to be able to afford to live in New York City.

I’ve occasionally referred to this period as academic cryogenic suspension. I was still in research residence, so I never took a leave of absence. It took being offered the job at Brooklyn College, which was a visiting assistant professor position that would turn into a tenure-track position—once I had my degree in hand—for me to finish my degree in 2005.

You examine the culture of music recordings in your dissertation. What interests you about this theme?

My dissertation became my first book, Records Ruin the Landscape: John Cage, the Sixties, and Sound Recording [Duke University Press, 2014]. It’s about the culture of experimental music in the 1960s and the marginal role that sound recordings played in it. John Cage’s ideas were a revelation to me, and yet I was really struck by how ideological he seemed about dismissing recordings. You could ask about the culture of recordings for Cage in the 1940s and 1950s when he’s first composing and producing work. It was not a culture of independent record labels or artists. It was the sale of classical music with taglines like “Own all of Beethoven’s symphonies.” I think that Cage’s basic impulse was a moral one—this sense of “How could anyone presume to own music?” It’s Cage’s anarchism.

My love of recordings has everything to do with growing up in a place like Louisville, where I wasn’t able to see a lot of the live music that I was most interested in. I was really involved in making things. I started playing in punk bands at the same time that I started editing a fanzine. The material culture of recordings and how they circulated among teenagers was extraordinarily exciting to me. People in the hardcore punk scene in the 1980s were self-releasing records. They were designing the sleeves. It was never only about the music.

Your last three books comprise a trilogy of prose poems reflecting on music and performance. What brought about this shift?

My friend Ben Lerner, a poet who at that time was writing his first novel, had encouraged me to write a book of poetry. Also, poetry was primarily what I studied at Chicago—the major field of my comprehensive exam was twentieth-century American poetry. And in 2002 or 2003, I started doing performance works with the poet Susan Howe. I thought, Maybe I’m not too old to try my hand at this.

I had also been thinking about articulating ideas about musical practice that were rooted in my own experience. And I wanted to write something fictional. The first of the three books is Now That the Audience Is Assembled [Duke University Press, 2018], which is a description of a fictional concert of improvised music. I enjoyed writing it, and the two subsequent books, like no other writing that I’ve done before.

You mentioned that your next book will be about working collaboratively.

Yeah. I don’t know the form of it yet. I’m not going to write a how-to manual. What I’ve done thus far is narrated, to the best of my recollections, first meetings with people with whom I wound up working collaboratively over a long period. I’m always interested in that intensity of the first encounter—in thinking about how much comes up in a first conversation with someone that is subsequently worked out over the course of multiple projects or multiple years. In my experience, those ideas that are expressed relatively early in getting to know someone echo forward for quite a ways.

What makes for a good collaboration, in your experience?

Working with brilliant, generous, and sane people is a good start.

Have you had any surprising collaborations?

The collaboration with Susan Howe, I feel, has been the most unlikely. I was a great admirer of Susan’s books from around the time I started graduate school. Poetry was something that I really dove into then. To have that experience come alive in a collaborative setting with a writer I could not admire more—I mean, I could have imagined writing a dissertation about Susan’s work in 1995—I can’t tell you how fortunate I feel to have been able to spend time working with her.

I like to be in a collaborative situation where people enjoy one another’s presence sufficiently and like one another and respect one another sufficiently that they can intervene in one another’s practice. It would be quite easy just to have a separation. I’m the composer, she’s the writer, that’s it. But so many decisions come to the fore when performing. Susan had a residency at the Gardner Museum in Boston about 10 years ago and called me up and said, “Would you consider coming up here and recording here? It’s the most marvelous soundscape right before the museum opens.” You hear footsteps from all the way across the museum. Aurally, there are these enormous vistas that are present. As soon as they open the doors and the first group of like high school kids comes in, it’s ruined. For her to take an active role in the process of collecting and composing sounds really was one of the most gratifying aspects of that collaboration.