In January Jacqueline Stewart, AM’93, PhD’99 (English Language and Literature), a professor in Cinema and Media Studies, became the chief artistic and programming officer for the new Academy Museum of Motion Pictures—a new venture by the organization best known for putting on the Oscars. As she was preparing for the in-person opening of the museum in September, she spoke with Tableau about her position at the museum, marginalized figures in film history, and her UChicago education.

Can you tell us what exactly the Academy Museum is?

It’s affiliated with the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. Most people think of the Oscars when they think of the Academy and don’t necessarily understand its broad, year-round reach as a professional organization covering every aspect of filmmaking from screenwriting to acting, directing, production design, costume design, hair and makeup—and more. What I’ve been really struck by is the commitment of Academy members to ensuring that the museum reflects work across these fields so that we can provide a comprehensive view of what filmmaking involves.

Could you explain your role at the Academy Museum in a nutshell?

I oversee the content and the intellectual mission of the museum, which is to give as complete and diverse a picture of the art of moviemaking as we can—and to do so in a way that covers all of the crafts of filmmaking and that explores the ways that film has developed across history, both as an art form and as a cultural institution.

Is there an exhibition you’re especially excited about?

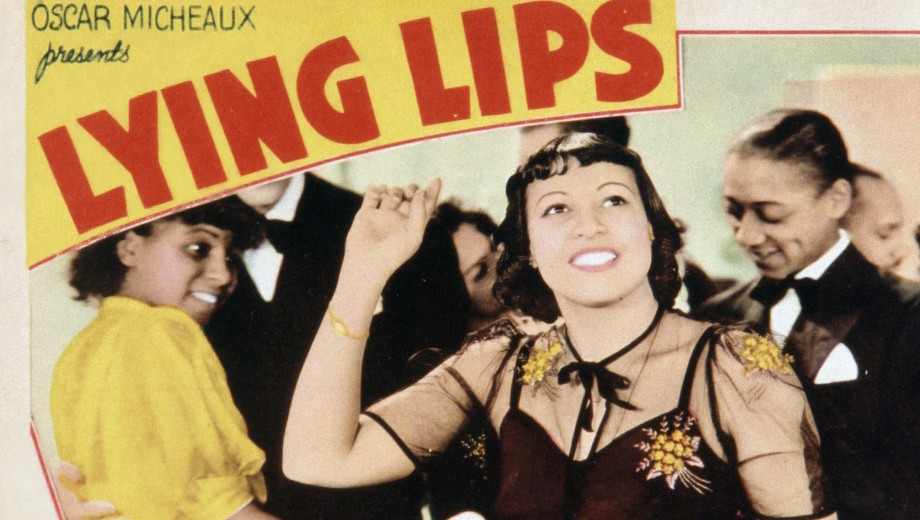

There’s the core exhibition, which is really ambitious. It’s called Stories of Cinema. It’s a three-floor exhibition that walks through the various craft areas of filmmaking. But what is exciting to me is the way that it starts with a set of vignettes—these kind of capsule narratives—of significant films and filmmakers. Not surprisingly, when people enter that gallery they see Citizen Kane. But we also feature the film Real Women Have Curves, which was directed by Patricia Cardoso, about the experiences of a young Latina in East Los Angeles. There’s a vignette focused on a filmmaker I’ve done a lot of research on, Oscar Micheaux, a pioneering African American writer and director who started his career in Chicago and made more than 40 films between 1918 and 1948 for segregated African American audiences.

I think that elevating narratives of filmmakers and types of filmmaking that haven’t been recognized before on this kind of platform is going to increase general public recognition of figures that hadn’t been known much beyond scholarly circles—and make unexpected connections that can inspire more diverse kinds of scholarly work.

So you see the museum as a resource for scholars?

Oh, absolutely. The curatorial team is incredibly talented. And the museum draws on the unparalleled collections of the Academy Film Archive and the Margaret Herrick Library. For me, the museum is also a space for developing career paths for film scholars beyond the academy. I never expected to work outside of a university. And we know that the academic job market for PhDs continues to be difficult.

How has the pandemic affected the planning and opening of the museum?

The museum was supposed to be ready to start welcoming the public around the time of the Oscars in April. When I came on board [in January 2021], we decided to start programming even though the building wasn’t going to be open. So we launched a series of virtual programs.

Our first program featured a discussion with four women who made Oscars history: Whoopi Goldberg, the first Black performer to be nominated for best actress and best supporting actress and the first person of color to host the Oscars solo; Sophia Loren, the first woman to win an Oscar for a non-English-speaking role; Buffy Sainte-Marie, the first Indigenous person to win an Academy Award, which was for cowriting the song “Up Where We Belong” for the movie An Officer and a Gentleman; and Marlee Matlin, the first deaf performer to win an Academy Award and the youngest person still to win the Best Actress award. It was interesting to have dialogue with them about the ways their career paths and perspectives have been shaped by the intersections of gender with other aspects of their identities.

How did your UChicago education set you up for this kind of work?

I’m also a native South Sider. So much of my research has drawn on that nexus of having grown up on the South Side and also being at the University when film studies was becoming a discipline that one could pursue here. I came in 1992. I studied with [late UChicago film professor] Miriam Hansen and [Professor Emeritus in Art History and Cinema and Media Studies] Tom Gunning, as they were forming what was then the Committee on Cinema and Media Studies. With the formalizing of cinema studies at the University, we were deeply immersed in questions of the relationship between cinema and modernity—to look at films not just as individual works of art but as works of culture that are deeply connected to social and political histories.

I remember vividly Miriam’s opening lecture to her Methods and Issues in Cinema Studies course. She reminded us that we were studying film at the University of Chicago, right next to the site of the World’s Fair of 1893. This was where Eadweard Muybridge presented his Zoopraxographical Hall, the first building dedicated to screening moving pictures. That grounding of cinema history in place and public life is key to the work I’m doing at the Academy Museum.