Clifford Ando, the David B. and Clara E. Stern Distinguished Service Professor in Classics and History, studies the law, religion, and government of the Roman Empire.

Ancient empires were and are often understood as having been constructed from disparate peoples, united and brought to a kind of unity by imperial action. But even at their height, forms of diversity persisted, and these were often described as constitutive rather than disruptive of the empire as a whole. The Roman Empire can thus shed light on a federal system like the United States, and vice versa.

In both cases, there existed local systems of law and regional cultures that were enabled by the central authority, but also pushed back against it, sometimes merely by their own existence. “That may be how they do it in Washington, but that’s not how we do it in Texas,” for example. In the Roman Empire, there were distributed areas of authority as well, whether in city-states or in provinces. The system probably commenced as an expression of the weakness of central state power, but its continued existence served as a check on central state power too. Their collaboration, including their friction, produced a kind of order and imposed a useful limit on domination.

Nevertheless, there also existed something like an overarching culture, with a set of ideals or myths. The Romans claimed a distinctive form of dress; they insisted that certain actions at law could only be performed in Latin; they spread a certain culture of spectacle. Over time, the entire empire came to celebrate a number of political rituals that notionally took place everywhere at the same time, on the same day. In this way, the extension of the empire in space, which threatened to fragment the political body, was surmounted by collapsing the distance that separated the peoples of the empire in another dimension, that of time. Distance was overcome via a conceit of simultaneity. We can’t be at the same place, but we can be at the same time.

This practice on their part sheds light on an important difference between their world and ours. Despite the gradual unification of the Roman Empire, their world remained diverse. But the potential tension between the material fact of diversity and the ideal of a national culture was never cashed out in practice. If a so-called “Roman” ritual was performed in one city in Aramaic and in another in Latin, this fact remained invisible to contemporaries. A Roman citizen in one place never stared into the Zoom screen of a Roman citizen elsewhere and said, you don’t look very Roman to me.

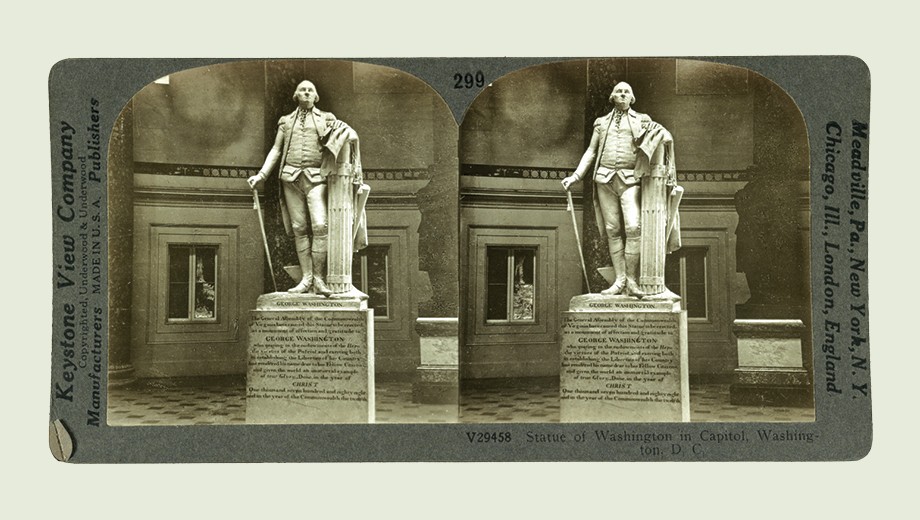

Today, new forms of communication technology that could unite us instead threaten to make forms of diversity that have always existed more apparent and perhaps salient than ever. Are the United States still united? Do we all think that George Washington chopped down the cherry tree? Can we understand each other when we speak? The visibility of such differences in behaviors and attitudes highlights our current crisis of knowledge: we no longer agree on facts, and we don’t even agree on mechanisms to decide what are facts. We thought we had, and shared, a culture of knowledge, born from these technologies of communication. It is profoundly concerning that these technologies have turned out instead to subvert and disjoin.

Chris Kennedy, the William H. Colvin Professor in Linguistics, studies the cognitive and social factors that enable meaning and communication. In Spring Quarter 2021 he is teaching a course on truth.

Political action is effected by linguistic interaction: we use language to describe situations and events from particular perspectives, in order to get others to form beliefs that will lead to specific courses of political action. Understanding exactly how this works can help us understand how it can enhance or disrupt unity.

Linguistic communication works because of a principle of trust. The words “Lavazza coffee is half price today only” characterize the world as being a certain way, but my saying them to you obviously doesn’t make the world that way. So how could they make you get up and go to the store? It’s because you trust that I believe those words to be true, that I have good evidence for that belief, and that I have a good reason for sharing it with you. No matter how much you love espresso, you shouldn’t make the trip if you think I’m fooling, or if you think my belief is based on wishful thinking instead of evidence, or if you think I have an ulterior motive, like getting you out of your apartment so I can steal your espresso machine.

That’s a mundane example, but the principles are no different when Donald Trump says things like “There was massive voter fraud in the 2020 presidential election.” Many people, including most legal authorities and the mainstream media, rejected such statements precisely because they lacked trust: it’s unclear whether Trump believed this claim, there certainly was no evidence to support it, and his reasons for saying it appeared to be less about ensuring election integrity than about staying in power. But we also know that many people accepted such statements, and so took the principle of trust to be satisfied: that Trump believed what he said, that he had evidence, that his reasons were not self-serving. These two positions are incompatible: trusting Trump means distrusting the mainstream media and the legal authorities who ruled against him, and vice versa.

The framework of trust that underwrites communication is not built “on the fly,” but is constructed and maintained over time, through our communicative interactions. Accepting claims about voter fraud reinforces a framework of trust that promotes acceptance not just of similar claims but also of unrelated claims by apparently like-minded people. It likewise leads to greater rejection of claims that are incompatible with this framework of trust, or made by differently minded people. And so on. Social media has exacerbated this problem, both because it enables us to say more things to more people with less connection to evidence than ever before, and because it promotes separation into like-minded groups of “friends” and “followers.” Eventually our frameworks of trust and belief have diverged so much that we can barely communicate at all. And if we can’t have a substantive conversation about whether the public health benefits of mask-wearing outweigh the costs in loss of personal liberty, or whether the benefits of investing in clean energy outweigh the costs of reducing fossil fuel use and production, then we will find it ever more difficult to make meaningful policy decisions about these issues.