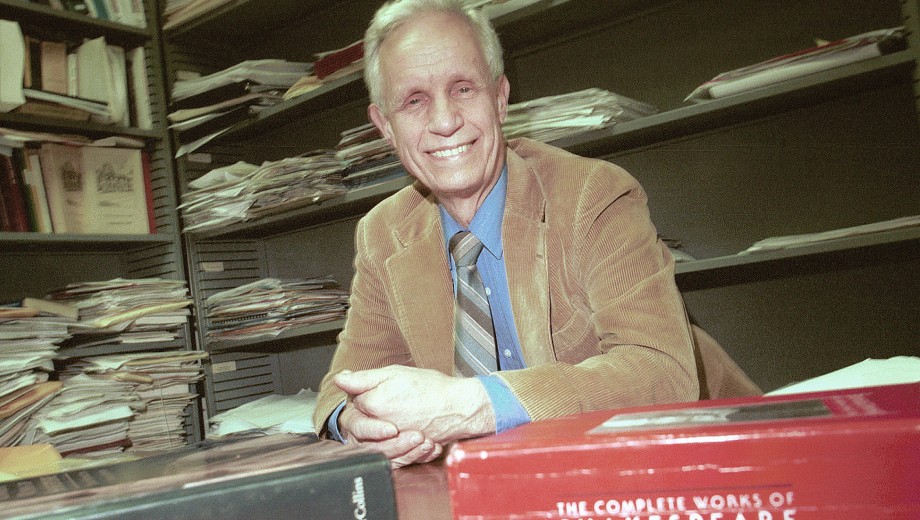

In memory of award-winning Shakespeare scholar and beloved UChicago professor David Bevington (1931–2019), Tableau presents a selection from his book This Wide and Universal Theater: Shakespeare in Performance, Then and Now (University of Chicago Press, 2007). In this excerpt, Bevington discusses how less can be more on stage.

When William Poel started his Elizabethan Stage Society in 1901 with an intent of restoring something closer to original Shakespearean staging, then, he was doing something revolutionary. His undertaking was both a historical restoration and a bold break with tradition. By abandoning expensive verisimilitude in favor of simpler sets nearly devoid of scenic representation, Poel revisited what he perceived as the essential idiom of the Shakespeare script, moving rapidly from scene to scene without a shift in sets, relying on the audience’s imagination to create the desired illusory effect. At the same time, by doing so he also aligned himself with a movement toward theatrical self-awareness that was to be further developed in the twentieth century by avant-garde playwrights like Samuel Beckett and by experimental directors like Peter Brook. The stage was now capable of being presentational rather than representational, that is, descriptively and persuasively aware of its own artifices of illusion rather than wedded to a literalist notion of showing what the scene appears to call for in representational terms. What seemed so new in this movement was also perceived as a recapitulation of the moving spirit of Shakespeare’s theatrical world.

At the heart of this discovery was the revelation of a paradox to which a great deal of modern theater is still committed: namely, that the more the theater eschews a literalist kind of realism, the more it invites the imaginative participation of the audience and thereby fosters a more active involvement of that audience. The result can be an intensifying of experience that increases rather than decreases a sense of what is “real.” The traditional proscenium arch theater, when compared with this experimental model, seems inert, relegated to a self-contained illusion of reality separated from the audience by the “fourth wall” of proscenium arch and curtain.

From This Wide and Universal Theater: Shakespeare in Performance, Then and Now by David Bevington. © 2007 by the University of Chicago. Reproduced by the publisher. All rights reserved.