Darby English is the Carl Darling Buck Professor in Art History and Adjunct Curator in the Department of Painting and Sculpture at the Museum of Modern Art, New York. His latest books are To Describe A Life: Notes from the Intersection of Art and Race Terror (Yale University Press, 2019) and Among Others: Blackness at MoMA (edited with Charlotte Barat, MoMA, 2019).

I’m not much interested in devoting the time that I set aside for reflection, research, and teaching to things that I don’t feel are creative—by which I mean they actually challenge accepted and instituted ways of thinking and acting in the world.

I have a reproduction in my office of one of William Pope.L’s “Skin Set” drawings. It displays the phrase “Black people are the trees in the park.” Now, black people are not trees. We know this, Pope.L knows this, and we know Pope.L knows this. The drawing’s creative moment is in using some common, seemingly neutral linguistic forms to emphasize the conventionality and excessively widespread nature of a violent and dangerous practice of description. Which is also a practice of substitution, substituting trees with black people and black people with trees. And we haven’t dealt with the park. They’re all wonderful things, but the wonder depends crucially on their not being confused with one another or reduced to abstractions. I could give a simpler example; I think I don’t want to. Because things that are actually creative are extremely rare, they are also highly idiosyncratic, as are our encounters with them.

A creative moment is a flashpoint. And of course it needs a context. If it’s not following the pattern, it may be manifesting creativity—for instance, in a domain where creativity is defined otherwise. This can be a big deal. But it’s not always called creativity. Sometimes we call it disruption or troublemaking or innovation. Those terms remind us that the word “creativity” does not have and should not have a universally positive valuation. It’s really easy to equate it with the good. Too easy. I want to know who’s talking, from what vision, to what ends?

Interpretation should also make room for creativity. This is important to me as a teacher and as a writer. Recognizing some quality in a thing you’re looking at is not a particularly creative way to interpret that thing. What you know about it in advance can foreclose originality in interpretation, especially if what you’re interpreting—a work of art, say, stakes its claim on creativity. What if it wants to make some difference from the thing you recognize? It’s on you as the interpreter to allocate or withhold space for that difference.

So, between what we might recognize and what’s actually creative there will be some remainder. Attention to all the factorable components of that remainder becomes crucial. Attention may be a necessary ingredient of creativity. Without it, you haven’t dealt with the thing. That limits the truthfulness of your interpretation, which in turn limits the amount of creativity a creative thing can release into the world.

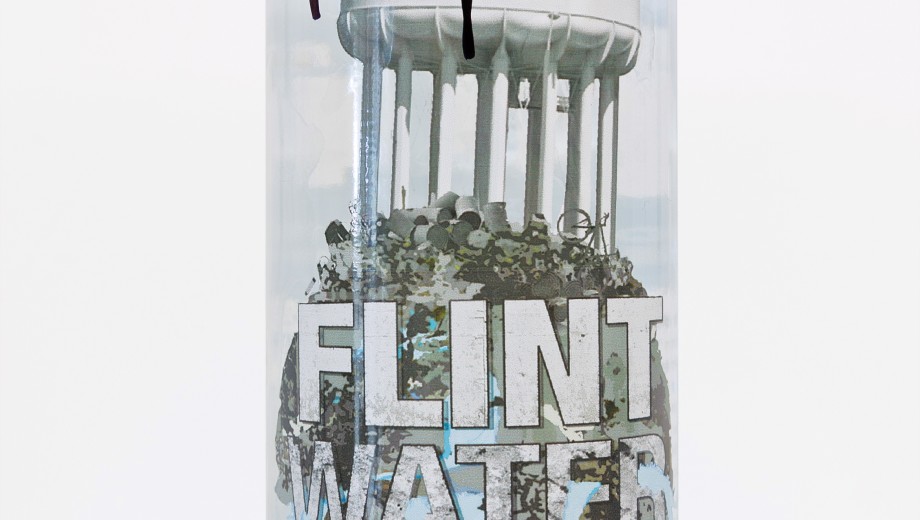

William Pope.L is an associate professor in the Department of Visual Arts. His work as an installation, performance, and intervention artist has earned him a Guggenheim Fellowship and has been included in the Whitney Biennial and Documenta 14. One of his notable recent works was Flint Water Project, an installation and performance piece that sold contaminated water from Flint, Michigan, at Detroit’s What Pipeline gallery.

I’ve been involved with creativity a long time now. It can feel like a gimmick, a tricky thing. The most interesting way of making things and thinking about making things is to give access to the making-process, forces, and situations that may seem counter to creativity. For example, sleeping, working blindly by feel, failing, procrastination, allowing others to make decisions for you—why do this? To create beyond individual limitations and logic. Doing it always with your eyes open. There is no magic, only making.

An idea by its lonesome is not usually sufficient. It is not enough just by itself for me to commit to it. I need to be able to build a bundle, a structure of ideas around it to see if it will support something more networked. How the bundle comes together determines this, the path this process takes. Every idea can be manifested in several ways, so there is always that. Flint Water was a commission. The ideas that became that project first bundled out through a set of conversations with the folks who help me run my studio. I like commissions; it’s like someone gives you a script to make into a movie.

Inspiration is overrated. People stereotype it as interesting or necessary. Actually, it’s the opposite or at least much more pedestrian than that. Inspiration distances, separates, puts at odds, inflates, projects onto. Less inspiration, more ignorance.

I also do not think originality is possible. Yet another gimmick. Because everything bundles, hinges to something else. That’s what’s interesting. The impurity of it all. Pure originality is a vacuum.

You always want to have your feet planted solidly on shaky ground. I am not sure if my work is political. A pundit once told me my work was merely social. At first, it hurt my feelings but eventually I got over it. Social may be lame, but it’s much less bullshit.

It’s important for art to appear special, magical, enigmatic. Even when it isn’t. Weirdly enough, it’s the appearance of work (or the lack of it) that can contribute to this illusion. Unlike real magic, a lot of art wants us to see the sweat, the technique, the effort (even the effort to erase effort should be in your face). This is not honesty; it’s the trope of good salesmanship. For example, there’s this thing we call a “finished product.” What is so finished about it? What tells us art is finished? It’s this sense of being concluded that is a trick.

Right now I am working on several things in my head. I am working on another play: Angelina Weld Grimké’s Rachel (1916). The NAACP commissioned it and hated it. My kind of play.