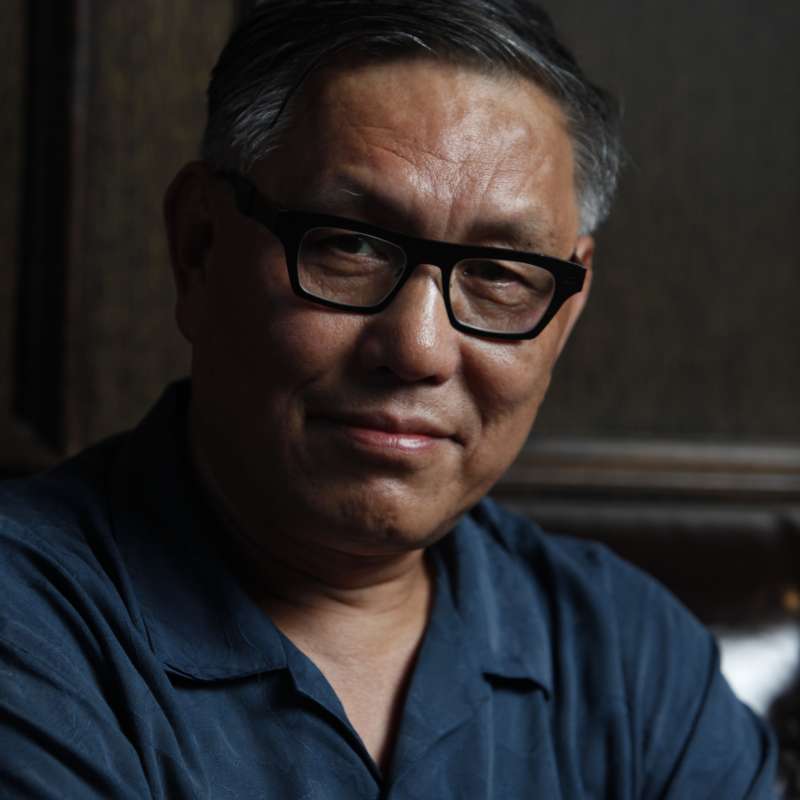

Wu Hung, the Harrie A. Vanderstappen Distinguished Service Professor of Art History and East Asian Languages and Civilizations, has spent a large part of his career shaping the field of contemporary Chinese art history and establishing contemporary Chinese art as a field for academic inquiry. In February the College Art Association recognized his work by naming him its 2018 Distinguished Scholar—the discipline’s highest honor.

The CAA award followed the announcement that Wu Hung, founder and director of the Center for the Art of East Asia at UChicago, will deliver the National Gallery of Art’s Mellon Lectures in 2019.

How did you become interested in art history?

After university at the Central Academy of Fine Arts (CAFA) in Beijing, I worked as a curator in the Palace Museum located in the Forbidden City. I actually lived inside the Forbidden City for eight years and was surrounded by ancient art. I had this intimate contact with history, which was extremely rare at that time during the Cultural Revolution. I returned to CAFA for graduate school and then moved to Harvard to get a PhD. Only after I came to the United States did this notion—that art history is a larger humanistic discipline—become clear.

What marks the beginning of contemporary Chinese art?

It’s determined by Chinese political history. During the Cultural Revolution, from 1966 through 1976, art became highly political—basically propaganda—controlled by the [Communist] Party. The end of the Cultural Revolution marked a profound change in art and literature. From the late 1970s to the mid-1980s, avant-garde groups started appearing and younger artists began to experiment with new forms and learn more from outside of China.

What challenges have Chinese post-Cultural Revolution artists faced?

In the 1980s they mainly tried to find a voice—a way to express individuality through visual forms. The ’90s saw many social changes in China, including the remake of urban space, new buildings, demolitions, migration. Artists reacted to those big changes. Still, there were few museums or galleries. Now there are many, but the artist has to struggle with commercial controls.

China was relatively isolated and is now a global country. Suddenly the whole world is open, but artists may wonder, where am I?

You’re curating a four-museum collaborative traveling exhibition on contemporary Chinese art, debuting at the Smart Museum in 2020. What’s the theme?

The Allure of Matter: Material Art from China, which is a collaboration between the Smart, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, the Seattle Art Museum, and the Peabody Essex Museum, goes beyond general introductions to contemporary Chinese art. It focuses on a particular trend—in this case materiality, the special materials artists use to create a personal visual language. For example, Cai Guo-Qiang was just here for an art performance using gunpowder as his material and medium. Other artists use hair or ceramic or even water. Some of these artists have been using such “personal materials” for 20–30 years, so it’s not just a one-time experimentation.

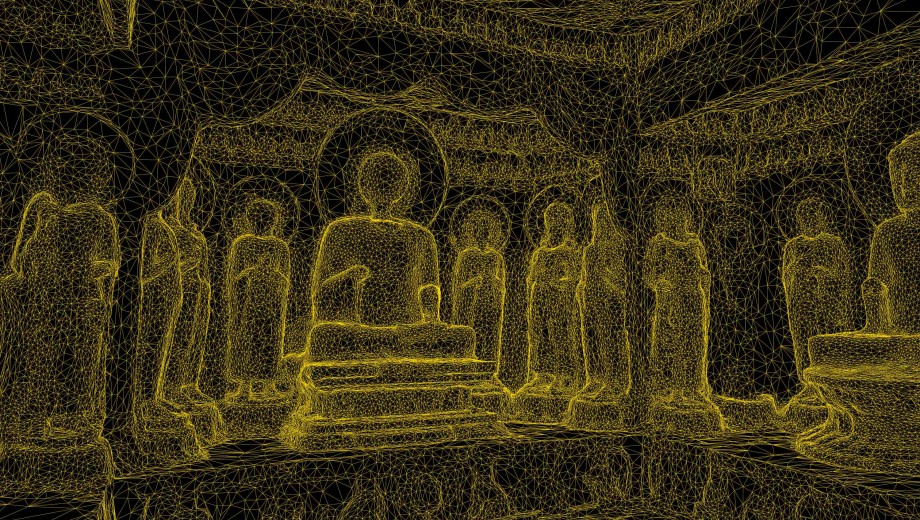

How did your work with 3D scanning in the Center for the Art of East Asia arise?

My predecessor, Harrie Vanderstappen, AM’51, PhD’55, began to study broken Buddhist statues from an architectural complex in China. The pieces were in different museums. He began to pay attention to the separation of the body and site. We now scan the site as well as the missing pieces and enter those scans into a database, available to scholars and students. Technology offers us the ability to digitally reconstruct these pillaged sites and the possibility to mend historical tragedy.

When I founded the Center for the Art of East Asia in 2002, I believed it should be cutting-edge, should indicate future directions. Just like contemporary art, it should be experimental, not just something everybody has been doing but future-oriented. So we turned toward technology.

We started with two projects, both of which are still quite alive. One project focuses on two Buddhist cave complexes at Xiangtangshan and Tianlongshan in China, developed with center deputy director Katherine Tsiang, PhD’96, and now working with another professor, Wei-Cheng Lin, AM’99, PhD’06.

The other is the Scrolling Paintings Project. Scrolls are a typical form of East Asian painting, which can reach ten meters or even longer. In art history education it is difficult to show those long, moving scrolls, so people typically cut them into pieces for slides and book illustrations. It totally changed the nature of the work—students cannot appreciate the rolling movement. So we worked with various museums to make the scroll move on a computer.

You’ve described your center’s Cave Project as a form of healing.

In art history, we are now very clear about the importance of sites and places, especially for religious or ritual art. You cannot separate statues and murals from original sites. But how can we reunite a broken cave? It is impossible to put it back together physically. There are logistical and political issues.

The separation of the statues here from the caves resulted from certain kinds of economic and political conditions—imperialism, colonization, warfare, antique trade, etc. How do we deal with this reality? No one can undo history, but as a historian, I feel we have an obligation to recognize certain injustices and find some way to talk about them. We cannot totally regain that sense of wholeness, because a whole was destroyed, but we can try to put pieces together using new technology. This effort is a kind of healing process.

Ironically, the destruction of the caves was partially encouraged by new technology during the early twentieth century—photography. Visitors photographed these beautiful caves, and they became known to antique dealers and collectors.

What new directions do you see art history taking?

One thing I’m committed to is asking: How do we talk about art history beyond national narrative? Current art historical narratives are linear histories based on particular countries or regions. Most art historians are experts on specific regions. We should find ways to talk about art historical issues on a higher level.

A few years ago, several professors in my department established a group called Global Ancient Art, initially consisting of historians studying ancient Greek, early Christian, Mayan, and Chinese art. We’re developing this conversation on how to find horizontal connections. We won’t abandon the notion of national or regional art history, but global art history is clearly part of the future for our discipline.