To truly study photography is to study original prints, experts say. Reproductions offer an adequate view of the subject, composition, and other surface characteristics of an image. But to understand the artist’s thinking behind the lens, scholars must consider how an exposure was taken as well as how it was crafted into the physical object in front of the viewer.

“It’s important to get students back to prints to show them what the experience of looking at a photograph was,” says Joel Snyder, professor in the Department of Art History.

“It’s important to get students back to prints to show them what the experience of looking at a photograph was,” says Joel Snyder, professor in the Department of Art History.

A print reflects a work’s intended size: a small, intimate frame that draws you in or an expansive scene that engulfs your field of vision. Materials, blemishes, and chemical composition also reveal details about artistic technique and historical context.

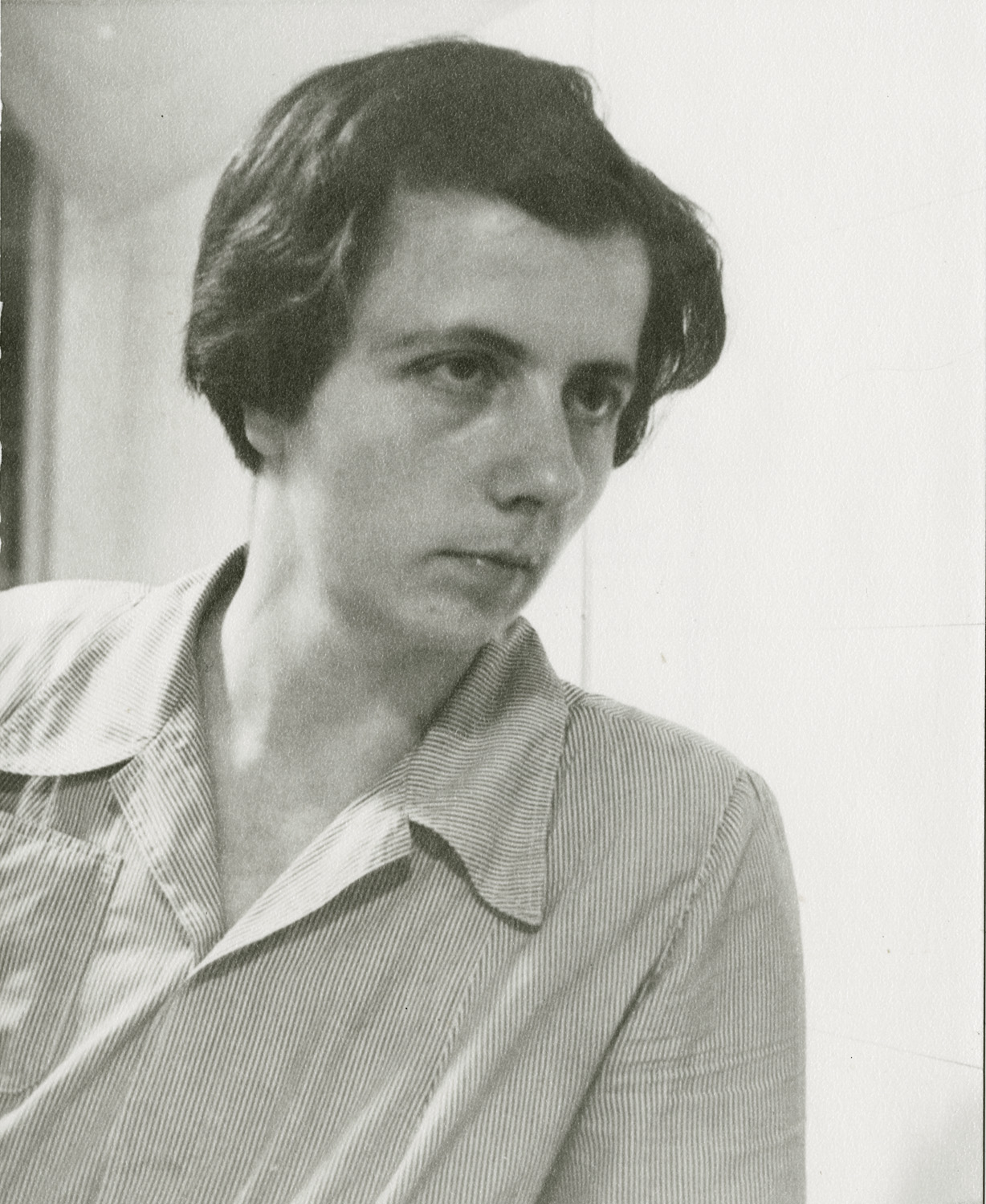

Prints are particularly important when it comes to Vivian Maier (1926–2009): a New Yorker turned Chicagoan who worked as a nanny to finance her obscure life as a world-class street photographer. And now UChicago students and scholars can study Maier’s handiwork up close at the University of Chicago Library.

Last summer, as an investment in Maier’s legacy, filmmaker John Maloof donated 500 vintage prints—made by the artist herself, either in her own darkroom or by commercial photo labs at her direction—to the Library’s Special Collections Research Center. The prints will be preserved and made available for research by current and future faculty and students.

“It’s amazing,” says Laura Letinsky, professor in the Department of Visual Arts. “The work that she produced is quite important and has been heralded as being on par with other photographers who had received much more attention at the time.”

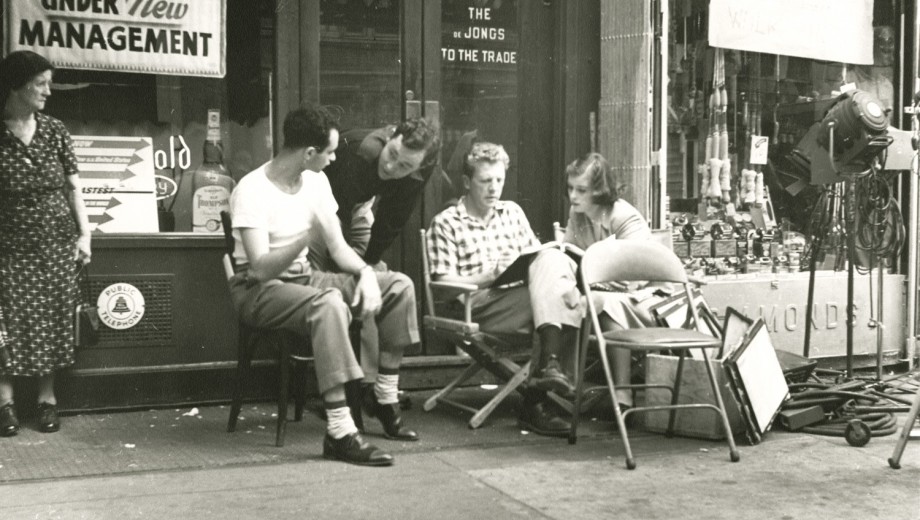

Maier’s career spanned from the 1950s to the 1980s, from rolling rural landscapes to close-up portraits of diners, commuters, and beachgoers immersed in their daily lives. John F. Kennedy, Eleanor Roosevelt, Pope John Paul II, Eva Marie Saint, and Frank Sinatra are just a few of the famous faces captured in her body of work—which she apparently never showed to anyone.

The spotlight found Maier at an auction in Chicago in 2009, when Maloof discovered several storage lockers with more than 100,000 of her photographs. Inspired by this hidden treasure, Maloof cowrote and directed the Academy Award–nominated documentary Finding Vivian Maier (2013), piecing together the mysterious photographer’s life and travels.

Daniel Meyer, director of Special Collections, told the Chicago Tribune he sees the collection gifted to the University as “an important part of the legacy of the graphic arts and photography in Chicago and America.” Students and scholars, he said, “will be very surprised to see [Maier’s] full range of work.”

Most exhibitions of Maier’s photography have featured large-format prints produced from her negatives by collectors. The University’s vintage prints are the only group of Maier originals to be made available for research in a library, and have never before been published or displayed.

Most exhibitions of Maier’s photography have featured large-format prints produced from her negatives by collectors. The University’s vintage prints are the only group of Maier originals to be made available for research in a library, and have never before been published or displayed.

“A lot of the work in this collection has [Maier’s] process visible. She’s printing in different ways, she’s cropping in different ways, and you can see her hand in the process,” Maloof says, describing the eclectic mix of prints, in both color and black and white, that he selected from his extensive archive.

The insightful, prolific, yet hidden nature of Maier’s work “speaks also to class and history and being a woman in a way that is quite important,” says Letinsky. As the collection is gradually processed (a years-long project) and made available for exploration, Letinsky looks forward to bringing her students to Regenstein Library “to talk about intentionality, about artistry versus some notion of originality.

“There are so many different ways this touches on important issues in contemporary art.”

The volume of this collection makes it a significant addition to the University’s growing assembly of art objects. Because it includes a broad sample of pieces from earlier and later in Maier’s life, it reflects the evolution of her work, adding her still-fresh commentary to ongoing academic discussion about her twentieth-century contemporaries.

Letinsky says Maier’s work, taken as a whole rather than as a series of standalone snapshots, reflects an “accumulation of ideas and approaches” that provides an important resource for photography and art history scholarship. “There’s no one person that we have this kind of depth of information about,” Letinsky says. The volume and range of the Maier collection enables students and scholars “to investigate fully a body of work.”

Particularly compared to digital images, Letinsky says, original prints provide a closer glimpse at an artist’s intentions. “It’s going to be really important for us to be able to get in there, look at the work, lay out the prints, compare them to other [artwork] that we see” in Special Collections.

Maier joins a growing number of women photographers represented in the Library’s Special Collections, including American Photo-Secessionist Eva Watson Schütze, anthropologist Joan Eggan, urban documentary photographer Mildred Mead, and literary photographer Layle Silbert.