Dear Alumni and Friends,

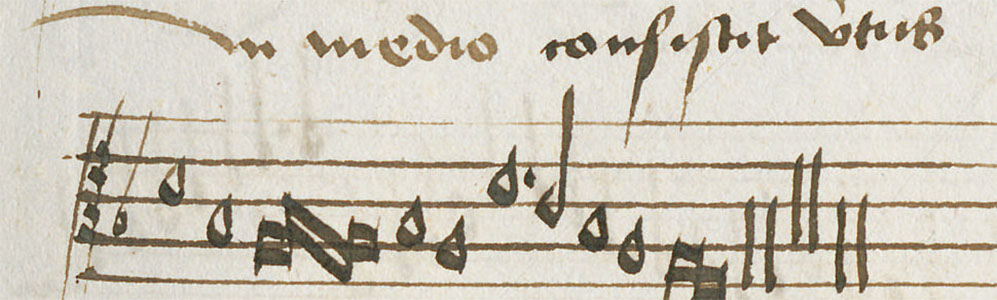

“Virtue stands in the middle.” I paused when I found this inscription in a fifteenth-century sacred musical composition by Flemish composer Jacob Obrecht. What was this phrase doing there?

I knew that the saying was paraphrased from Aristotle. But how did a line from pagan antiquity—“in medio consistit virtus,” as it reads in Latin in Obrecht’s mass—find its way into the Gloria and Credo of this composer’s masterpiece? I puzzled over this question for some time. Was it the “performance of virtue” that Shadi Bartsch-Zimmer (Classics) writes about in her insightful The Mirror of the Self: Sexuality, Self-Knowledge and the Gaze in the Early Roman Empire? Was it a harbinger of Napoleon’s struggle with the conflicting values of virtue and self-interest, as lucidly described by Robert Morrissey (Romance Languages and Literatures) in The Economy of Glory: From Ancien Régime France to the Fall of Napoleon?

In the end, the answer emerged in part because of something that our late colleague Michael Camille wrote in his seminal study of the margins of manuscripts in Image on the Edge: The Margins of Medieval Art. In the Middle Ages, people read books by studying both the main text on the page and the commentary that appeared in smaller letters around the edges. “Virtue stands in the middle” is one of these glosses: an explanation of a line of Boethius’s timeless Consolation of Philosophy. It means that a virtuous person should stand her ground—in the exact middle, in fact—between the opposites of adversity and prosperity, and should resist being drawn, through lack of moderation, to either extreme. Here was an explanation that spoke to the theological context of Obrecht’s mass.

As you can see, I have learned a great deal from my colleagues in the Division of the Humanities in three decades as a member of the Department of Music, and I am deeply honored now to serve as interim dean for 2016-17. My goal for the Division this year is to help every member of the faculty produce the most innovative research and teach our students in inspiring ways. These are the things that we do best: promote new ideas and encourage the next generation of scholars.

Let me close by thanking Martha Roth. For nine years Martha guided our Division as dean and has more than earned her return to scholarship and teaching. Martha’s skill and vision leave us positioned for further success, and it is my privilege to continue this Division’s legacy as a worldwide hub of humanistic thought and inquiry.

Anne Walters Robertson

Interim Dean, Division of the Humanities

Claire Dux Swift Distinguished Service Professor, Department of Music