A tour of Buzz Spector’s St. Louis studio necessarily includes a tour of his bookshelves.

“Here’s the poetry. The critical theory,” he says, pointing to different sections. “My favorite books don’t just include artists’ books and monographs.”

Spector, MFA’78, is fascinated by books as both subject and object. His art—featuring volumes he has made, built with, and altered—has been exhibited at galleries around the world, including the Art Institute of Chicago, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, and the Centro per l’Arte Contemporanea Luigi Pecci in Prato, Italy.

He grew up surrounded by books and went to college at Southern Illinois University in Carbondale with an eye toward a career in creative writing. When “a D in poetry convinced me that maybe English wasn’t my thing,” Spector says, his creative impulses drew him toward visual art. He chose the University of Chicago’s visual arts program—then known as the Committee on Art and Design—in part because he could take any kind of academic course, anywhere in the University.

“I wanted to immerse myself in philosophy as well as studio practice,” says Spector, who’s taught at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Cornell, and now at the Sam Fox School of Design and Visual Art at Washington University in St. Louis. He drew inspiration from assistant professor Richard Shiff, an insomniac who often dropped by Midway Studios in the middle of the night, when Spector was working, to “critique my work as I was making it.” He also talked ideas, philosophy, and literature with his neighbors in an apartment building south of the Midway: Brent Staples, AM’76, PhD’82, now a New York Times editorial writer, and David Shields, AM’75, PhD’82, an English professor at the University of South Carolina. Along with Reagan Upshaw, AM’76, and Upshaw’s wife, Roberta, he started WhiteWalls, a magazine of writings by artists.

“The basis of my entire career as an artist and writer was established in those years in Hyde Park,” Spector says. After finishing his MFA, Spector spent three years editing publications at the University’s Graduate School of Business, now Chicago Booth. The job not only afforded him an employee discount to print WhiteWalls but it also led to a career break.

As a grad student, Spector had written a paper for Shiff’s contemporary art history seminar on the relationship between minimal art and corporate graphic design. Shiff showed the paper to Renaissance Society curator Suzanne Ghez, suggesting that Spector organize and curate an exhibit on the topic.

To prepare for the exhibit, Spector picked the brains of business school professors, who explained how changes in the legislation covering business expansion across industry categories helped contribute to the international style of graphic design: as companies diversified and acquired new, often disparate, divisions, they needed an all-encompassing visual image. “I could not have gotten those insights in the art world,” Spector says, “where it was a completely unacknowledged, invisible relationship.” The exhibit, Objects and Logotypes: Relationships Between Minimal Art and Corporate Design, ran in early 1980. A quarter century later, Art in America called it “a prescient model for understanding the complex, often shifting relationship between art and corporate culture.”

In the studio, meanwhile, Spector was drawing and making wall-mounted shallow-relief sculptures by gluing the edges of strips of paper directly to the wall or onto backings, so the stiff paper would project into space. Using lighting angles and black paper, Spector found “a kind of perceptual interest” in playing with shadows, sometimes to the point where a viewer could barely differentiate shadow from solid.

But “what wasn’t in that work for me,” he says, “was an engagement with language.” After all, the great attraction to UChicago was what he calls its “intellectual-critical” emphasis.

So he changed focus—first to books that had been annotated by readers. For a while, he haunted Hyde Park’s Powell’s and O’Gara and Wilson’s bookstores, “looking for densely overwritten books.” But other artists were doing similar work, and Spector eventually shifted to changing the form or function of a book while keeping its essence as a book.

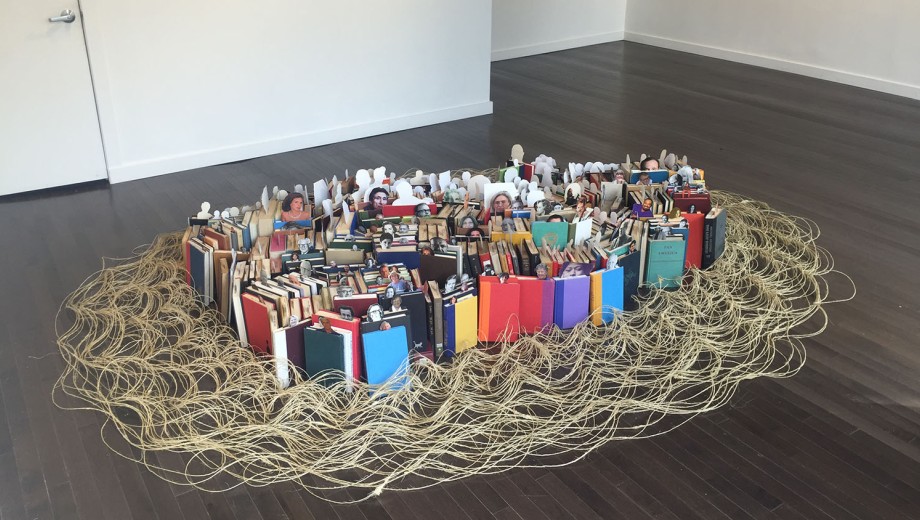

For example, in one of his latest works, Writ Large, exhibited at Milwaukee’s Ski Club gallery this past April, he plays with the idea of choosing what books someone might take to a desert island, by making an actual island out of books.

Spector has also taken an increasing interest in creating the words that fill the books. While he has written about art since his WhiteWalls days, he’s added more writing to his schedule, “warming up” for a book of essays: some new, some previously published—and not all about art.

In pursuing his interests wherever they lead him, Spector uses the same approach he takes with his students. “We’ll often have long conversations about unrelated matters,” he says, “at least as the young artist construes it. I’m trying to get my bearings about where there’s an extra enthrallment, an absorption, in the practice.”