In addition to being modernist scholars, art historian Megan Sullivan and English Language and Literature PhD student Rachel Kyne also illustrate the often porous boundaries between humanistic disciplines through their scholarly paths. While Sullivan earned her undergraduate degree in comparative literature and became an assistant professor of art history, Kyne studied visual art in college and is now in the dissertation year of her PhD in English Language and Literature.

They’ve both always had interests in literature and visual art. Sullivan took art history as well as literature courses as an undergraduate at Brown. Like her current area of study, Sullivan’s undergraduate thesis focused on Latin America, but a slightly later period: how popular culture—primarily US movies and music—functioned in contemporary Latin American literature.

When she was deciding where to pursue her graduate studies, she was torn between the two disciplines.

“I was interested at the time in how images and language do or don’t produce meaning in the same way,” she says. “I thought that art history would allow me to ask these questions in a broader way and still incorporate my training in literature.”

In fact, early in graduate school, Sullivan was interested in the way text and image relate, “how they function differently, but how we can think about them together.”

Kyne grew up as voracious reader and writer but also played classical violin and considered a career in music before enrolling at the Emily Carr Institute of Art and Design in Vancouver to study painting. Like Sullivan, she kept a hand in the literature and art worlds through her undergraduate career, working at Carr’s writing center beginning in her second year.

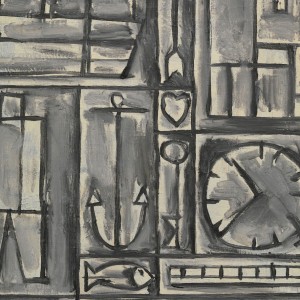

“Visual artists often have tremendous communicative powers, but not in written genres,” she says. Kyne’s graduation project “shows the back and forth” between the two media: a suite of three large oil paintings, accompanied by text that is a combination of critical essay and original poetry.

For Kyne, it was precisely her varied artistic interests that made modernism so fascinating.

“Modernism is a moment of just tremendous cross-collaboration between poets and artists,” she says. “Artists were defining their movements, or giving names to their manifestos, or expanding their ideas through the patronage and friendship of poets and writers.” As an example, she cites the French writer Guillaume Apollinaire, a close friend of Picasso’s and one of the first people to celebrate the cubists.

Add new comment