About 13 years ago, Mark Usher, AM’94, PhD’97, now chair of the classics department at the University of Vermont, was working on an article about what Socrates might have looked like. In the Republic, Socrates is described as “a snotty-nosed kid.” Usher, the father of three sons, was struck by how childlike Socrates was: “Asking annoying questions, not letting things go. Plus he was against all the adults. I thought, this is a character that kids will like.”

Usher—an assistant professor at the time—had never written a picture book before, but he had spent countless hours reading them aloud to his children. Using the books of Peter Sís as models, and with his youngest son Gawain, then four, in mind, he wrote a simple biography of Socrates. Usher recounted the philosopher’s imprisonment, for example, like this: “Then they sent him off … to jail! Socrates was sad. ‘Nevertheless,’ he said, ‘it is still better to suffer a wrong than to commit one.’” Sidebars supply more detailed information for advanced readers or parents. The structure echoes “the classical form of text and commentary,” says Usher. “As a classicist, that’s your stock in trade.”

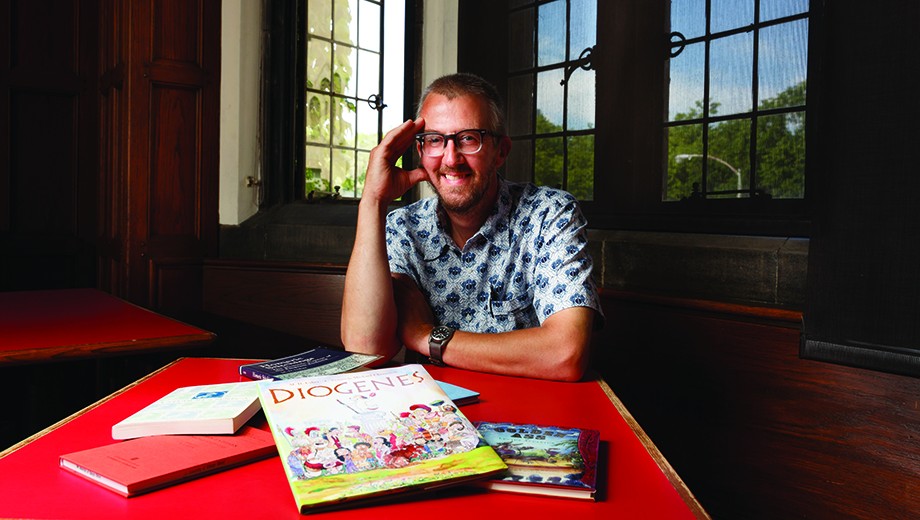

Usher knew no one in children’s publishing, but he sent his manuscript to five or six publishers. Three years passed before it emerged from the slush pile at Farrar, Straus and Giroux; Usher had all but forgotten it. “I didn’t realize until after the fact how lucky I was,” says Usher, whose academic publications include A Student’s Seneca (2006) and Homeric Stitchings: The Homeric Centos of the Empress Eudocia (1998). “Compared to getting a children’s book published, getting an academic book published is easy.” Wise Guy: The Life and Philosophy of Socrates came out in 2005 and received positive reviews in Publisher’s Weekly and Kirkus Reviews.

A few years later, work on another academic article—this one about Diogenes’s quotations from Homer—inspired Usher to write another picture-book manuscript. In a biography told entirely in limericks, Usher portrayed Diogenes, the founder of the Cynic (Greek for “dog-like”) school of philosophy, as an actual dog. Usher’s editor liked the story, but not the limericks: “Some of them were rude, some were a little too sophisticated,” says Usher, who published a revised, prose version of Diogenes in 2009—the same year his article “Diogenes’ Doggerel” appeared in Classical Journal.

Kids love to say the word ass. Here’s the chance for them to do it in a legitimate context.

His most recent children’s book, an adaptation of Apuleius’s The Golden Ass for older readers, came out in 2011. The comedic novel had long been one of Usher’s favorites. “Kids love to say the word ass,” he says. “Here’s the chance for them to do it in a legitimate context.” Usher hoped the book’s title would incite controversy: “It would get so much attention if it were banned from libraries.” But so far no luck.

*******

Usher dates his interest in illustrated manuscripts back to graduate school, when he was asked to curate a 1994 exhibition at the Regenstein’s Special Collections Research Center. “Texts and Transformations” focused on classical works and their adaptations in different genres and media—including music and visual art—through the centuries. To make the exhibition and its catalog interesting, “we wanted to have splashy volumes with illustrations,” he says. It was the first time he had thought seriously about the juxtaposition of text and image.

Usher’s research for the exhibition also inspired his dissertation, which became Homeric Stitchings. In a 1502 collection of Christian poetry published by Aldus Manutius, Usher discovered something he had never seen before: a poem on Biblical themes, composed entirely in language taken from Homer. It was a cento (pronounced with a hard “c”), from the Greek word for stitching: a type of poem consisting of passages taken from other authors. Eudocia Augusta had crafted this particular cento in the fifth century.

As Usher studied the poem, he realized the Aldus version differed from other versions, and all were incomplete. He identified what seemed to be the definitive manuscript in a catalog of the libraries of Mount Athos in Greece, home to more than 20 Eastern Orthodox monasteries. But the catalog had been compiled in 1890, before a major fire.

If the poem manuscript had survived, it would be bound with others, so Usher had to physically search for it.

With a fellowship from the University, he traveled to Greece, not knowing if it was a fool’s errand. In a Hollywood-like moment, the librarian, Father Theologos, “cracked this big book, dust goes everywhere, and we found the manuscript,” says Usher. “Then a younger monk came by and threw it on the photocopier.” Usher’s second book was a critical edition of the text, Homerocentones Eudociae Augustae (1999), published just a year after Homeric Stitchings.

Usher no longer works on centos, but he writes them. In 1999, collaborating with the composer John Peel, he wrote the libretto for the opera Voces Vergilianae. The story of Dido and Aeneas is told using lines taken from throughout the entire Aeneid, “so they serve as intertextual commentary on the whole poem,” he says. “The Dido and Aeneas episode is really what the whole poem is about—westward expansion, Rome’s march to world domination and all the victims that are in the way, Dido being one of them.”

He’s working on another libretto about the Roman emperor Nero with the same composer, using ancient Greek and Latin texts. Selections from this work-in-progress were performed in concert this past March; the full opera will premiere in Salem, Oregon, in 2016. Usher has also written a cento for children, POEM, a picture book about poetry stitched together from the lines of famous poems: “Some poems come in on little cat feet / Some wander lonely as a cloud / And some beat boldly on a big bass drum / And tell even Death to not be proud.”

In addition to his academic and creative work, Usher, a trained carpenter, built his own farmhouse in Shoreham, Vermont. He and his wife, Caroline, home-schooled their three children: the oldest, Isaiah, graduated from Princeton; the middle, Estlin, AB’13, from UChicago; the youngest, Gawain, is studying viola at Interlochen Arts Academy.

The couple raises sheep, poultry, pigs, and goats on their farm, called Works & Days after the poem and farmer’s almanac written by Hesiod around 700 BCE. “I do the PhDing around the farm,” says Usher. “That’s post-hole digging.” But that’s a story for another place and time.

Comments

context of a quote

Sir:

Many decades ago I read a quote I liked by Juvenal, which began "Pray for a brave heart, which does not fear death, but places a long life last among the gifts of nature. . . "

at the time I diligently searched through hard copies at the library to find the full text - to no avail. i believe it was from a satire - can you direct me to a full translation? I would so love to read the whole thing in context.

context of a quote

I would suggest you send your query to Professor Usher, via his University of Vermont web address. Good luck!

Juvenal's Satires

This is one of my favorite quotes. It's from Juvenal's Satire X at the very end. Good luck!

I'm inspired!

I loved reading about your work, especially as I'm a poet and writer and I teach in the UVM English Department. I particularly loved the reference to your POEM which uses lines from famous poems. What a great way to introduce children to poetry!