A UChicago scholar talks about redefining African American literature and making the novel Invisible Man visible onstage.

In his latest book, What Was African American Literature? (2011), Kenneth Warren argues that African American literature belonged to a specific historical period that began in the 1890s and ended in the 1960s. “Like it or not, African American literature was a Jim Crow phenomenon,” Warren wrote in a Chronicle of Higher Education essay based on his book. “African American literature is history.” Some readers did not appreciate this notion, as evidenced by the pages of vitriolic web comments: “Patently absurd and insulting,” was one reaction.

In contrast, Warren’s role as adviser to Court Theatre’s production of Invisible Man in early 2012—the first time Ralph Ellison’s novel had been adapted for the stage—was far from controversial. Reviewers and theatergoers loved the play: “A remarkable, 205-minute, must-see, three-act dramatic achievement,” raved the Chicago Tribune’s reviewer.

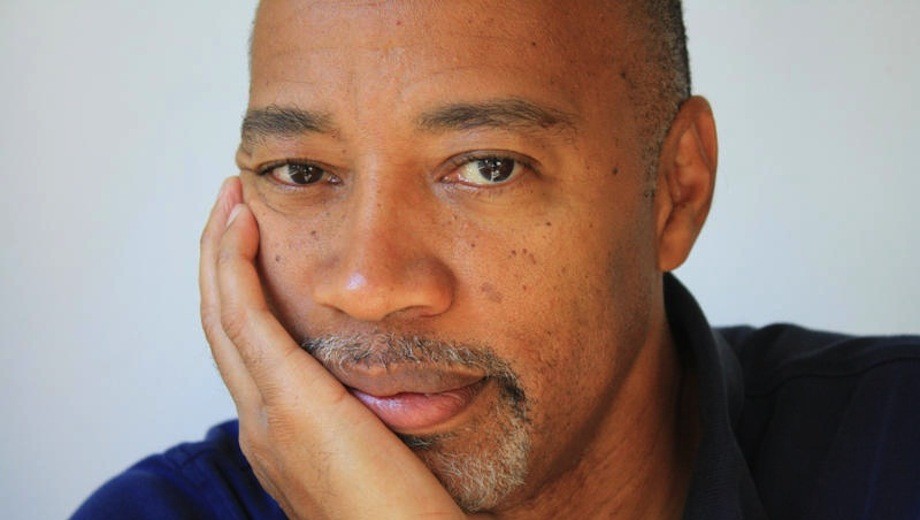

Warren is the Fairfax M. Cone Distinguished Service Professor in English language and literature and the former deputy provost for research and minority issues. A member of the UChicago faculty since 1991, he is the author of Black and White Strangers: Race and American Literary Realism (1993) and So Black and Blue: Ralph Ellison and the Occasion of Criticism (2003).

Do you remember the first time you read Invisible Man?

Oh yes. I went to high school in Albuquerque, New Mexico, and black writers weren’t really being taught. So I began to read some of this literature on my own. It’s a powerful story—the story of a young man with a great deal of ambition, but not a lot of wisdom, trying to find his way into adulthood. That really spoke to me.

At the time I knew I probably wanted to study literature in college, but I don’t think I realized I would end up spending so much time on Invisible Man.

What was your contribution to the Court Theatre production?

My first concrete involvement was attending a staged reading about a year ago. I was a bit skeptical about any kind of stage adaptation until then. But the reading drove home how powerful the characters’ speeches are, even with the actors just sitting there. Ellison had a great ear for spoken language.

I read two versions of the stage-play adaptation, and had discussions with the director [Christopher McElroen] and the writer [Oren Jacoby]. The main task was how to cut the novel down to a manageable size, and how to work the scenic transitions to move the narrative forward. It received very good reviews. "Like it or not, African American literature was a Jim Crow phenomenon." Deservedly so—especially since the playwright and director were working under strict constraints imposed by the literary executor of Ellison’s estate. All the language in the play had to be Ellison’s. The playwright could not take a speech by one character and put it in the mouth of another, so there was no possibility of using composite characters. Obviously scenes would have to be cut, but the order could not be rearranged. And if that weren’t enough, there were specific scenes that had to be included.

Why do you think Ellison never completed his second novel?

In So Black and Blue, I speculate that Invisible Man is so powerful because Ellison was so attuned to the social, political, and aesthetic situation of the Jim Crow era. He published it at the cusp of the post–Jim Crow era, two years before the Brown v. Board of Education decision.

Ellison was strongly committed to the idea that the novel, as a form, needed to process and understand the present. And I feel that he never figured out how to do that in the new political order emerging around him.

Is that how you came up with the idea that African American literature ended with the Jim Crow era?

It was related, yes. I started thinking about the appropriations of Ellison’s work by a variety of scholars and activists. I wondered, what is it about Ellison that makes him seem so available?

It was related, yes. I started thinking about the appropriations of Ellison’s work by a variety of scholars and activists. I wondered, what is it about Ellison that makes him seem so available?

If we feel that Invisible Man speaks to us in the current moment, well, that might be an inaccurate assessment. However much racism continues, it is not the same problem as it was under Jim Crow.

Could you explain why the end of Jim Crow also ended African American literature, according to your definition?

Imaginative African American literature first begins to emerge in a moment of great disenfranchisement in the South. Beginning in the early 1890s, state constitutions were rewritten to effectively move the black population out of political life. African American writers, quite self-consciously, wanted to act as a voice for a politically silenced population.

Under those conditions, many of the writers—and I do try to provide significant examples of this in What Was African American Literature?—are themselves wondering, if they were successful at overturning the political conditions that made this literature so important, what would be the status of this literature?

Under Jim Crow, one could see why someone writing a poem and getting it published in a major journal could count as an argument against the Jim Crow system. Racism "is not the primary vector of inequality." And in counting against Jim Crow, the publication of that poem had implications for people who didn’t write, who didn’t read. We are no longer at that moment, when the success of a particular black individual could call attention to the falsity of racist beliefs and affect all blacks, regardless of their class status.

Were there any authors who made the transition that Ellison didn’t—that is, who wrote some books that you would consider to be African American literature and also wrote some you would not?

Toni Morrison’s first novel, The Bluest Eye (1970), was written at this transitional moment that I’m talking about. Perhaps that one work falls within the historical protocol of African American literature. But the work that she does afterward is not part of this literary project.

Why are some people so offended by your argument? What do they hear when you make it?

Sometimes they hear the claim that racism no longer persists as a problem. It does, and it needs to be addressed. However, it is not the primary vector of inequality.

I argue that it’s important to address racial bias, but attacking racial bias is no longer a project that’s a challenge to the system. It is part and parcel of the system. All major institutions understand that it’s part of their role to guard against bias, to seek out a diverse population.

I’m not saying they all do this well, or that there isn’t opposition. But the operating norm for major institutions in this country is that a diverse workforce is a good thing.

In 2010, you ended your second term as deputy provost for research and minority issues, a role that you helped create. How is the University doing on diversity issues?

Overall, Chicago is a more diverse institution than five or ten years ago. At the faculty level, these numbers are highly volatile, because the numbers are relatively small. Three or four new hires make a banner year; two people leaving is a bad year. But the trend has been quite positive.

You were recently awarded a Humanities Visiting Committee research grant. What did you use it for?

I’ve submitted a collection of critical essays for publication on Sutton E. Griggs, an African American writer from the turn of the century. It’s part of a larger project to bring the five relatively obscure novels that he published from 1899 through 1908 into a set of critical editions and draw some attention to them.

I also helped put together an interdisciplinary conference called Jim Crow America: A Problem in Historicization, in April 2012. Our goal was to explore the benefits and limitations of viewing this period as differing significantly from the forms of subordination that came before and after.