THE MEDIEVAL MANUSCRIPTS are laid out on a long table—and yes, Christina von Nolcken tells her students, it’s OK to handle them.

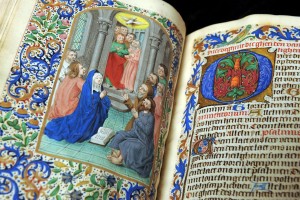

The oldest is a twelfth-century volume recounting miracles of the Virgin Mary. There is an annotated version of Boccaccio’s epic poem Teseida and a colorfully illustrated book of hours, both from the fifteenth century.

Each relates in some way to Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales, the focus of an undergraduate course that von Nolcken, an Associate Professor in English, teaches annually. She holds today’s session in the Special Collections Research Center (SCRC) of the University of Chicago Library, so students can get a closer look at books created and read around Chaucer’s day.

Forty students peer at the manuscripts; some turn pages and lift the books gently from their foam cradles. Visitors to Special Collections must leave their belongings in lockers and can bring only pencils and paper into the classroom—but nothing is under glass, and no gloves are required for handling.

Von Nolcken urges students to enjoy the privilege. “Never will you be in a library, ever again, where they let you touch these manuscripts in the same generous way as they allow at the University of Chicago,” she says. “Never will you meet with such trust again.”

AT A TIME WHEN DIGITAL IS REPLACING PRINT and course readings rarely require a trip to the library stacks, many Humanities faculty feel committed to using original sources in teaching. From medieval manuscripts to papyrus fragments and jazz recordings, the materials at the University are rich and varied.

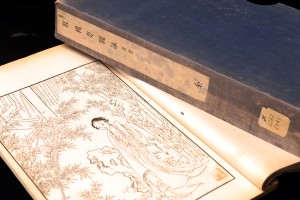

This fall, Judith Zeitlin, a Professor in East Asian Languages and Civilizations, is teaching two courses that bring students into direct contact with primary sources. The first, a graduate seminar on the historiography of Chinese literature, meets adjacent to the library’s East Asia Collection. Students begin by examining a rare sutra-scroll manuscript from the tenth century and continue onward to study woodblock-printed novels from the nineteenth.

“One reason I’m meeting in the library is because these things are so heavy that I don’t want to have to schlep them somewhere else,” jokes Zeitlin. More importantly, she wants students to see how short stories, novels, and plays came to be written and circulated in premodern China. For her humanities Core course on world literature, Zeitlin’s students examine cuneiform tablets at the Oriental Institute so they can imagine how the Epic of Gilgamesh might have first appeared. At the SCRC, they look at multiple versions of the Iliad and Odyssey to get a sense of how presentation and translation of the texts have evolved over time.

Their idea of the text being stable is destabilized from the moment they enter Special Collections.

Typically, undergraduates read classic works “all in the same form, like Penguin paperbacks,” says Zeitlin. The site visits aim “to get them to understand that it’s not just the literary form, content, and context but also the material form, especially in the ancient world, that would have shaped the way these things were translated and passed down as texts.”

READING HOMER is a rite of passage for students in the College, but exposing them early to the library’s remarkable Iliad and Odyssey translations was the brainchild of Erin Fehskens, who teaches a Core course on epic literature. For her own research on epic and the transatlantic slave trade, Fehskens had consulted the Bibliotheca Homerica Langiana collection, a 2007 gift of Michael C. Lang, and other items that highlight Homer in translation.

Working with librarian Julia Gardner, she arranged for her students—all first-years—to have a look at the collection just after arriving on campus in fall 2009. (Gardner and David Pavelich are reference and instruction librarians who support faculty and student use of the SCRC.) “Many of them have no idea that something like Special Collections exists, or that they can have access to it,” says Fehskens, a Collegiate Assistant Professor in the Humanities and Harper-Schmidt Fellow.

“Physically getting them into the room was so important,” she adds. “There was quite a bit of wonder when they came in, and I liked that.” But wonder soon gave way to critical thinking as students scrutinized crumbling papyrus fragments of the Iliad, written in Greek in the second century, C.E., and now held together by glass plates. “When they see how much of it is missing and how difficult it is to read, they start to understand that the text they have today is not something that came down pristine over the years,” explains Fehskens. In short, “Their idea of the text being stable is destabilized from the moment they enter Special Collections.”

Students appreciate the lesson. “Being allowed to access actual historic manuscripts of the sources we were looking at shows us how civilizations have shaped our view of classic works,” says Samantha Ngooi, Class of 2013. Adds Renee Cheng, who compared translations of the Odyssey from William Morris (1887) to Edward McCrorie (2004) for the class, “It was interesting to look at how translators’ word choices influenced the interpretation of the text.”

JUST AS A MODERN PAPERBACK GIVES A NARROW ACCOUNT of ancient Greece, musical recordings only scratch the surface of American jazz. Travis Jackson, an Associate Professor in Music and the College, tapped resources in the Regenstein Library to give students in his fall 2008 jazz course “a more participatory experience.”

“Handling original materials helps students to better understand how scholars put together narrative and interpretive historical accounts,” says Jackson. “Rather than argue with secondary sources based on what they’ve seen or read in other secondary sources, they have to confront materials that don’t come with a ready-made, already-provided context.”

Exploring the library’s Chicago Jazz Archive, students zeroed in on venues where jazz was performed locally from the 1920s onward. “The idea was to have them move away from understanding the history of jazz solely through recordings, which document only the tiniest bit of the daily practice of musicians,” says Jackson. By studying clubs like the Green Mill and Velvet Lounge—and perusing artifacts like photographs, news articles, posters, programs, and ticket stubs—he hoped students would see “the interconnectedness of ideas about performance with those about urban space, political economy, gender, sexuality, and other issues.”

Going back to an entirely different era—fourteenth-century France—music scholar Anne Robertson held a graduate seminar in the library to study a single, seminal manuscript. Special Collections owns a superb facsimile of the Roman de Fauvel, lavishly illustrated with art miniatures and notated with music. Using a document camera and giant plasma screen, “We were able to study every detail of the book closely, from its intricate musical notation to the smallest flourishes of the illuminations,” says Robertson, the Claire Dux Swift Distinguished Service Professor in Music. She also ordered other manuscripts and prints in Special Collections to compare them side-by-side with the Fauvel facsimile. For students of early music, such opportunities are essential, Robertson argues: “There is simply no substitute for hands-on experience with original sources.”

FOR BOTH NOVICE AND EXPERT HUMANITIES SCHOLARS, a library and its collections serve as a vital research laboratory. New technologies and digitization have revolutionized access to materials, but in-person study of primary sources remains equally important—and one does not preclude the other.

Indeed, a 2006 study of library use at the University showed that “the use of electronic and physical materials increases and decreases together.” Heavy users of books, manuscripts, and other artifacts are also heavy users of digital resources. Not surprisingly, the same study revealed that faculty and graduate students in the Humanities Division access the library more than anyone on campus.

One “heavy user” is Eric Slauter, an Associate Professor in English and Director of the Scherer Center for the Study of American Culture, who uses archival sources extensively in his own research. He taught two courses in the SCRC recently, including History of the Book in America. For one session, he laid the table with not a sampling but a feast of original sources.

Slauter showed students a 1791 edition of Benjamin Franklin’s Autobiography and his 1750 Experiments in Electricity, of which the Regenstein “has just about every edition ever published.” He found a copy of The Federalist, “the only essay to make it into book form and gorgeously bound. Feel the weightiness of the stock,” he urged. The class also perused vintage almanacs and newspaper clippings, U.S. currency in plastic sleeves, and a Thomas Tryon treatise on vegetarianism that convinced Franklin to foreswear “filth, fish, and flesh."

Admiring the gold leaf on a handsome leather binding or turning the stiff, vellum pages of a medieval prayer book isn’t idle bibliophilia. Slauter aspires to make a book’s context come alive—so students consider primary sources along with recent scholarship on textual production and reception. Admiring the gold leaf on a handsome leather binding or turning the stiff, vellum pages of a medieval prayer book isn’t idle bibliophilia.To gain a broad perspective on early America, his course examines “the histories of authorship, publishing, dissemination, distribution, and transmission on the one hand; and the histories of reading, listening, and viewing on the other,” according to the syllabus.

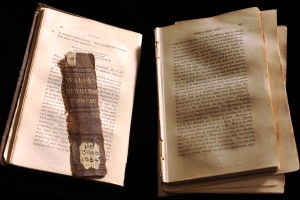

In another course, How Walden was Made, Slauter and his students got so close to a pair of first editions of Thoreau’s classic that they named them “Good Walden” and “Bad Walden.” Both published in 1854, “Good Walden” is in mint condition while the “bad” copy is falling apart—allowing it to be dissected from every possible angle. “We’d often show up to class and there would be originals of whatever we were looking at waiting for us at our seats,” says Lawrence Belcher, Class of 2011. “It was awesome.“

“I’m more inclined now to crave the input of original texts,” adds Belcher. Studying primary sources gives you “a grasp on the way people are thinking and the way politics and social life move and change throughout time.”

NO ONE IS HAPPIER THAN LIBRARIANS when students and professors request and appreciate precious books. “Ours is a working collection that is here to be used,” says Alice Schreyer, Director of the SCRC. “This seems an obvious goal for any part of the library, but the fact that we actively promote reading, studying, and handling materials in Special Collections sometimes surprises those who know us primarily from exhibits and think of us as a museum environment.”

This year, a major renovation will improve research, instruction, and exhibition spaces in Special Collections, and when the University’s new Joe and Rika Mansueto Library opens in spring 2011, visibility of and access to all collections will increase. A bridge will connect the Mansueto and Regenstein libraries; visitors will be able to view the latest exhibits in the SCRC as they walk along a pathway from one building to the other. In a new group study room, students and faculty will collaborate on projects and consult materials.

Undoubtedly, as the humanities navigate the twenty-first century, both print and electronic resources will continue to shape teaching and research. And at Chicago, scholars who need a jazz recording or a medieval prayer book, a Chinese scroll or a dozen different translations of Homer, will continue to find them on campus—as well as new discoveries along the way.