In April, the University formally announced the creation of a center in Beijing, China, portending opportunities for scholars in all disciplines including the humanities. Scheduled to open in fall 2010, the University of Chicago Center in Beijing aspires to be an intellectual destination for faculty and students and a home for collaborative scholarship in three main areas: business, economics, and policy; science, medicine, and public health; and culture, society, and the arts.

Why China? “Essentially we wanted a substantial physical presence that goes beyond study abroad, that truly elevates the intellectual exchanges between an American institution and Chinese institutions,” said Dali Yang, director of the Center for East Asian Studies. Yang, a political scientist who headed the committee recommending the center’s creation, has been named its first faculty director.

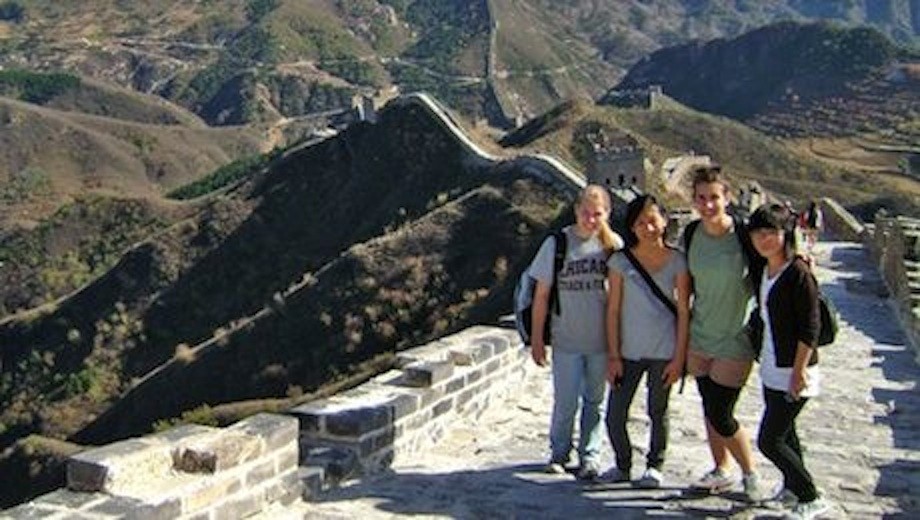

Chicago has a long tradition of faculty research and exchanges in China; graduate students from diverse disciplines also do fieldwork and language study there. Since 2006, the College has run an East Asian civilizations program in Beijing which aims to move to the center’s new headquarters in the Haidan District by September. Once established, the Center in Beijing will be the University’s fourth What will a permanent presence in China mean for Chicago scholars in the humanities?location abroad, joining existing campuses in Paris, London, and Singapore. Administrators and faculty are also considering a proposal to create a University of Chicago institute for advanced study in New Delhi. Tableau asked several distinguished faculty from the Division of the Humanities to share their thoughts about what a permanent presence in China might mean for scholars; we share their reflections below.

Shadi Bartsch, Ann L. and Lawrence B. Buttenwieser Professor in Classical Languages and Literatures and member of the faculty steering committee for the Center in Beijing: “Five years ago, I went on a trip to China; I took a barge down the Yangtze River. And it was fascination at first sight, with the culture, with the language. It felt as if I was looking into a new intellectual world. I started taking Chinese classes here at the University and wanting to learn more about China—and I started thinking in terms of my training as someone who studies classical literature in the West and how interesting it might be to learn about classical literature in the East, to see what kind of role that literature played for that culture. Then I found out that the University was thinking about opening this center. It was wonderful because it wasn’t just a question of getting people at Chicago who were already experts in China to participate; it was also opening up a new area to people who were curious about China, who were interested in China’s appearance on the world scene, who were fascinated by its long tradition of literature and science, but who didn’t know much about it. We’re opening up a center there as much to learn as to offer our own take on things.”

[wysiwyg_field contenteditable="false" wf_deltas="0" wf_field="field_article_images" wf_formatter="image" wf_settings-image_link="" wf_settings-image_style="" wf_cache="1363363836" wf_entity_id="4897" wf_entity_type="node"]

Donald Harper, Centennial Professor in Chinese Studies and member of the faculty committee recommending the establishment of the Center in Beijing: “In my own field, we’re already deeply involved in collaborations with Chinese colleagues and ongoing projects with scholars at various major universities in China. To me what’s important about the center is the face it will give to the humanities and the opportunities that it opens up for graduate students and undergraduates. In many ways the most exciting possibilities are not for those of us who already have our contacts and research in place, but for people in other disciplines, who will now have easier access to collaborative work in China. The other side of it is that the Chinese themselves are engaged in major efforts to bring a broader awareness of Western scholarship into the Chinese academic environment. That includes major translation projects and collaborations not just in Chinese studies but in anthropology, European languages and literatures, sociology, and other fields. There’s a great possibility for the Chicago center to be a point of contact with North American scholarship.”

Robert Morrissey, Benjamin Franklin Professor of French Literature, who helped found the University’s Center in Paris and served on the faculty committee recommending the establishment of the Center in Beijing: “Right now I’m teaching a course on Montesquieu’s L’esprit des lois and China plays a central role in this, strangely enough. You could easily imagine having a very interesting encounter around Montesquieu in China; there’s a whole current of debate in France between Sinophobes and Sinophiles that is central to 18th-century thought. Throughout the Enlightenment, China is an example of a kind of empire that leaves Montesquieu perplexed, in a sense. There’s a whole question of how large a country should be and the relationship between size and the type of government. This is an example of how the Center in Beijing can be an opportunity for developing a wide variety of activities among scholars. As a committee, we met with the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences and they were very interested in collaborations that would range across the humanities and social sciences. They are eager to collaborate with the University of Chicago. In fact, every institution that we went to showed a great warmth and desire to find various levels and types of collaboration. It’s the right time, and Beijing is the right place.”

Edward Shaughnessy, Lorraine J. and Herrlee G. Creel Distinguished Service Professor of Early China and Chair of East Asian Languages and Civilizations: “Each year, my department and the University’s Creel Center for Chinese Paleography host the Herrlee G. Creel (PhB’26, AM'27, PhD’29) Memorial Lecture here in Chicago. For next year we had hoped to be able to host Professor Li Xueqin of Qinghua University in Beijing. Professor Li is the greatest living authority on all aspects of early Chinese cultural history. Unfortunately, he is now 77 years old and his doctor has advised him not to take long-distance trips. To accommodate him, we have now invited him to speak at the Center in Beijing, just down the road from his own university, and to webcast it to Chicago—and perhaps to other universities as well. In the future, we look forward to using the Center in Beijing and this sort of technology in many similar ways. For the University to have a footprint in China is important.”

Add new comment