Forty years ago, Latin American art was largely unknown beyond Frida Kahlo or Diego Rivera. Today, Latin American artists feature in major museum exhibitions, sell their work for millions of dollars, and are increasingly studied by art historians, in part because of the efforts of Mari Carmen Ramírez, AM’78, PhD’89.

As the Wortham Curator of Latin American Art at the Museum of Fine Arts Houston (MFAH), and previously at the Blanton Museum of Art at the University of Texas–Austin, Ramírez has built what the New York Times described as one of the top collections of Latin American art in the world. She developed blockbuster exhibitions such as 2004’s Inverted Utopias, which featured South American avant-garde artists who had rarely been seen in the United States—including Brazil’s Lygia Clark, Venezuela’s Gego, and Argentina’s Xul Solar. That exhibit, among others, prompted Time magazine to name her one of the 25 most influential Hispanics in America in 2005.

Under Ramírez’s leadership, in 2012 the MFAH launched the International Center for the Art of the Americas, a digital archive of more than 12,000 primary source documents—letters, manifestos, and other texts that provide, she says, “access to the intellectual production of the artists.”

Ramírez talked to Tableau about the past, present, and future of Latin American art scholarship.

Was anyone involved in Latin American art history when you were at UChicago?

There was absolutely nobody in the United States who was teaching Latin American art. But I was lucky that Reinhold Heller had just started at Chicago. He was a specialist in German expressionism and Edvard Munch. When I explained to him what I wanted to do—on the notion of nationalism and Latin American art—he said, “Well, I can’t teach you anything about Latin America, but if you’re interested in nationalism, start with Germany. I can teach you a lot about that.” That was a very typical University of Chicago thing.

I spent three years studying German art, but he also allowed me to do a number of independent courses, especially literature and literary studies, and I was able to really work my way into Latin American art while being in Chicago on my own.

Was German art helpful?

Yes, absolutely, because my real passion since then has been the study of the avant-garde, and that was the basis for it. I did a lot of theory of the avant-garde: Peter Bürger, Theodor Adorno, Walter Benjamin. We studied every single chapter of the avant-garde, from impressionism all the way to the second world war. It was really fascinating.

There are two ways of studying Latin American art, or any kind of art, for that matter: one is to be completely immersed in courses about Latin America, and another is to do it by way of this more general introduction to modernism. I still favor the second one because it gave me the perspective to then approach Latin American art on much broader terms.

What was the perception of Latin American art during your doctoral studies?

People in the United States, whether curators, collectors, or art historians, they just did not care about Latin American art. They thought it was derivative, they thought it was inferior, it had all been done before. Art historical studies were not as advanced as they are today, so there was little to change their minds. It was pretty much an uphill battle.

But the landscape has changed a lot since then.

The whole shift began in the late 1970s, with the establishment of the first specialized auctions of Latin American art at Sotheby’s and then Christie’s. That started a market. But it’s only been since the late 1990s and 2000s that the field has really picked up significance as a result of global trends. It’s all intertwined with the rise of the financial markets, closer contact, neoliberalism in Latin America, and the emergence of a class of financiers who turn to art as collectors but also as investors.

And then there is the rise of curators, particularly my generation. I happen to be part of a generation of curators, particularly in Latin America, who are the first to choose deliberately to become curators rather than academics.

My education in Chicago was certainly all academic: very theoretical, very historiographic. And I could have pursued that line to go on and teach. But I was always—perhaps because I’m part of the generation of the 1970s—trying to find ways to transform institutions and to work from the inside. Curatorial practice was a very exciting and emergent field at that time, and it offered the possibility of working in a different arena: closer to the public, but that still had all of the scholarly aspects.

What do you think of the growing movement to consider art history more “horizontally”— beyond national or regional boundaries and more globally?

That’s a very important tendency right now, which I think is absolutely necessary. It’s in many ways the way I initially approached it from the limitations in Chicago, having to study European art and Latin American art.

But you need to have art historians or scholars who are deeply grounded in the country or region that they’re working in for them to make connections to whatever happens anywhere else.

Because of our traditional subordinate status and colonial history, Latin American scholars have by necessity to study all of the Western tradition. They need to have the Western tradition as a referent, and now they probably also study Asia or something else.

That’s not the case for scholars coming from Europe or the United States. You can’t just have somebody parachute into these countries because they happen to know a lot about modernism and postmodernism and approach this in any kind of intelligent or serious way.

I really advocate for both. There’s still so much work to be done with Latin American art, so many artists that need to be studied, so many movements, that it requires a specialized approach.

One of the museum trustees said you helped put the MFAH on the map.

The fact that the MFAH decided in 2001 to establish a major program in Latin American art that included not only a curatorial department but a research center—and that they put a significant amount of money behind that initiative—was the factor needed in the field to launch it into the mainstream.

MFAH did it strategically to position itself as a leader in the field, and it did it at a point when the identity of this museum was not completely consolidated. Latin American art was an area we could lead. The artwork was still available, it was still relatively reasonably priced, and so Peter Marzio [AM’66, PhD’69], who was the director at the time, was able to see the difference that was going to make. He was a true visionary.

I consider Peter my professional mentor. One of the reasons we got along so well was because we both have the Chicago education. At Chicago there’s always this concern between theory and practice, connecting both. And it’s not something that you’re taught—it’s not a course. It’s something that’s in the atmosphere: in what you think, in what people are talking about. Milton Friedman [AM’33] talked about that a lot, how there was no use in doing theory if you didn’t have the facts to support it, or have facts if you didn’t have a theory. That’s one of the great takeaways that I took from Chicago, which really helped shape my entire career.

At this point, artists like Wifredo Lam, Joaquin Torres Garcia, and obviously Diego Rivera and David Alfaro Siqueiros are pretty well known to people interested in art. Who are some other more recent or more obscure artists that people should know?

This is something that distinguishes my professional trajectory, which is the fact that—with the exception of the muralists, who at the time when I studied them were criticized by others—I have basically been involved with artists who are not recognized.

I’ve never done any work with Frida Kahlo—I’ve actually been very critical of the whole phenomenon of Frida Kahlo—and I haven’t done any work with the other “blue chip” Latin American artists. My interest lies with bringing to the table unknown artists, unknown talents, people who are many times recognized in their countries but not known outside. Or they’re completely unknown or misunderstood even in their own countries.

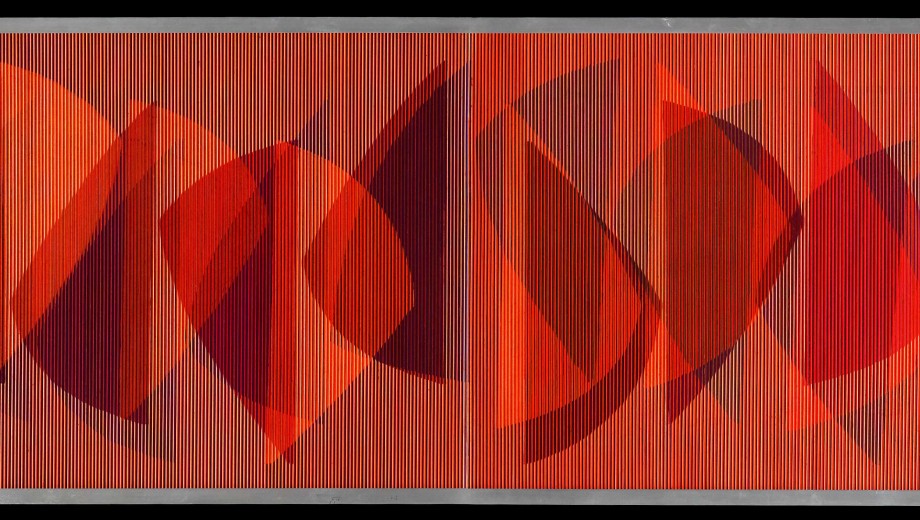

For instance, our next exhibition in October is bringing out 150 works that basically constitute an unknown chapter in Venezuelan art but also in Latin American art. It’s an exhibition about the Venezuelan informalist movement, which operated between 1955 and 1975. With the exception of a handful of artists, all of the artists we’re showing there are completely unknown in the United States, and they have amazing work.

One of the most outstanding artists in that group is Elsa Gramcko. She’s an artist who worked in the abstract vein and is basically self-taught but obviously in touch with everything that was happening, not only in Venezuela but outside of Venezuela in terms of informalism and this fascinating work that we’re only now trying to pull together and understand.

You have many artists—particularly in the 60s and 70s—in Argentina and other countries that suffered dictatorships, who were never able to be projected outside of their country because of the dictatorship. For example, in Argentina you have Juan Carlos DiStefano, a magnificent sculptor from the 60s who works with very large monumental sculptures made out of fiberglass.

I’m also working on a retrospective of Beatriz González from Colombia, along with my colleague Tobias Ostrander at the Pérez Art Museum Miami. We’re doing the first full-fledged retrospective of this artist who’s sort of the grande dame of Latin American art. She’s in her 80s and has done amazing work, very experimental, based on recycling images, icons of Western art history.

In Brazil you have artists like Carmela Gross, a mid-career artist who also has extraordinary production and is not well known outside of Brazil. And then you have all the Latino/Latina artists here. That’s a completely different topic, but it’s one I’m very much involved with.