Historian Rebecca Messbarger had been wandering Bologna for hours, searching for a treasure few Italians knew existed. Before her stood an austere building guarded by a heavy iron fence. Could this be the place?

She ducked inside and spotted a porter’s office.

Empty.

She continued down the corridor.

Deserted.

Feeling more like an intruder than a researcher, Messbarger, PhD’94, tiptoed upstairs and peered down a long hallway. Finally, a discovery.

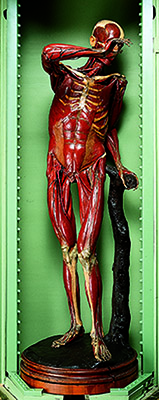

Floor-to-ceiling glass cases lined the room. Inside each stood a life-size wax figure, the skin omitted to reveal a crisscross of muscle and sinew. One model covered his eyes. Another seemed to gaze across the horizon. Known as écorchés—flayed men—the models had been part of the pope’s anatomy museum in the eighteenth century. Now they were neglected curiosities, languishing in an empty hallway at the University of Bologna’s Institute of Human Anatomy.

But they were not the main reason she’d come. Walking past the models, she spied a gold plaque above the far doorway. Its Latin inscription bore the name she’d been looking for: Signora Manzolini.

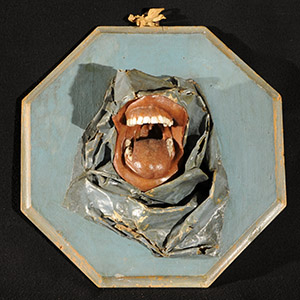

Inside the room sat a replica of Anna Morandi Manzolini—created in wax. An anatomical modeler during the Italian Enlightenment, she had been celebrated for her exacting sculptures of human organs and systems. Intended as scientific training tools, her pieces were based on real bodies obtained from the city morgue. During her lifetime (1714–74) crowds of physicians, medical students, and the curious would gather in her home to watch her anatomical demonstrations.

Sadly, the signora had not aged well. Marooned in the neglected museum, her self-portrait bust wore a tattered dress and brown wig placed haphazardly on her head. Straw filling poked out her back. Below her cracked fingers rested the likeness of a human brain, ready for dissecting.

Once admired by Pope Benedict XIV and Russia’s Catherine the Great, the modeler had been all but forgotten. As Messbarger stared at the decaying remnants, she vowed to put Anna Morandi back on the map.

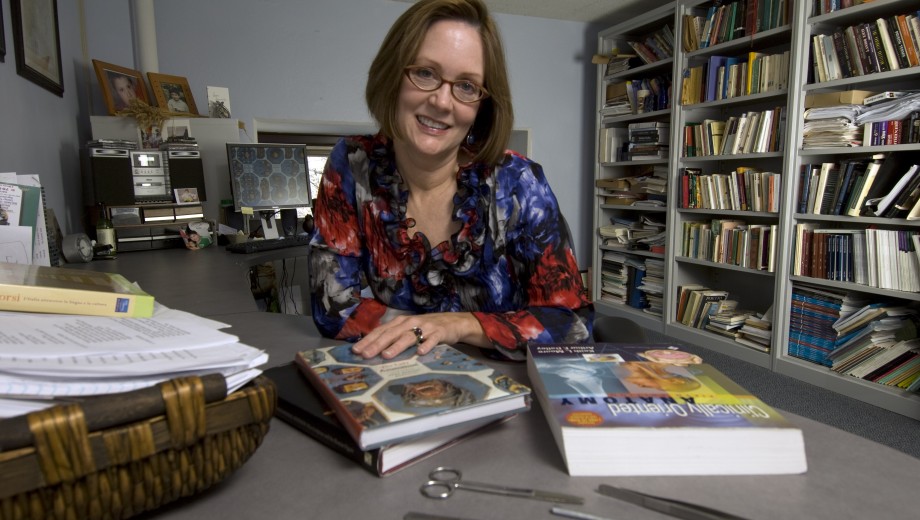

“I’m looking at this thinking, ‘This is so fantastic,’ but no one really knew about it,” recalls Messbarger, who first discovered Morandi while doing dissertation research on women’s intellectual authority during the Italian Enlightenment. “There are these very strange female biographical resources from the nineteenth century with lists of women and a couple sentences about their contributions. I kept running across her name.” Messbarger, now a professor of Italian as well as women, gender, and sexuality studies at Washington University in St. Louis, reintroduced the sculptor to the world with The Lady Anatomist: The Life and Work of Anna Morandi Manzolini (University of Chicago Press, 2010).

“I’m looking at this thinking, ‘This is so fantastic,’ but no one really knew about it,” recalls Messbarger, who first discovered Morandi while doing dissertation research on women’s intellectual authority during the Italian Enlightenment. “There are these very strange female biographical resources from the nineteenth century with lists of women and a couple sentences about their contributions. I kept running across her name.” Messbarger, now a professor of Italian as well as women, gender, and sexuality studies at Washington University in St. Louis, reintroduced the sculptor to the world with The Lady Anatomist: The Life and Work of Anna Morandi Manzolini (University of Chicago Press, 2010).

Messbarger unraveled the riveting story of an innovative female scientist underappreciated even in her own time. Trained as an artist, Morandi spent a decade doing dissections and anatomical modeling with her husband, Giovanni Manzolini. They sculpted teaching pieces for Bologna’s first obstetrics school and for academies throughout Europe. When Giovanni died in 1755, she continued their work and became a lecturer at the University of Bologna.

Despite her accomplishments, says Messbarger, Morandi was often seen as a “savant” rather than a scientist with serious preparation. Contemporary biographical accounts cast her as a “female improviser” and assumed she was merely her husband’s assistant.

“None of that was true,” says Messbarger, who mined Morandi’s detailed notebooks and eyewitness accounts of dissections to debunk the myths. Well versed in anatomy and medicine, Morandi led the couple’s public demonstrations, educating audiences about the human skeleton, sensory organs, and even male and female reproductive systems.

“None of that was true,” says Messbarger, who mined Morandi’s detailed notebooks and eyewitness accounts of dissections to debunk the myths. Well versed in anatomy and medicine, Morandi led the couple’s public demonstrations, educating audiences about the human skeleton, sensory organs, and even male and female reproductive systems.

Even as she gained international recognition—she received commissions from the Royal Society of London and Catherine the Great tried to recruit her to move to Russia—Morandi remained marginalized in her native Bologna. The city’s conservative Clementina Academy of Art believed the rawness of wax anatomical figures debased the noble depiction of the nude. Caught between the worlds of artist and scientist, she won acceptance in neither.

It wasn’t until her husband’s death that financial pressures prompted Morandi to request a stipend from Pope Benedict XIV that would allow her to continue as a public modeler. Recognizing her value to his native city, he arranged for her to receive 300 lire annually and an honorary membership in the art academy.

“He was a great supporter of select women intellectuals,” says Messbarger, who is now coediting the first English-language volume about Benedict XIV. A church reformer and patron of modern anatomical science, he was a central Enlightenment figure who, like Morandi, has been largely neglected. The project pulls together scholarship in medicine, religious studies, art history, and women’s studies, and has ambitious aims. “We’re really hoping that this work changes eighteenth-century studies,” she says, by raising the profile of this central figure.

Messbarger’s interest in the role of female intellectuals—and those who encourage them—is a personal one that goes back to her days at UChicago. “The fact that there were two women, Rebecca West and Elissa Weaver, among the leaders of the Romance Languages and Literatures department was important to me,” she says. Coming from a master’s program elsewhere with a nearly all-female student body and an all-male faculty, “I was ready to be mentored by women academic intellectuals.”

That training gave her the confidence to pursue her curiosity to eighteenth-century Bologna. “One of the things I found at Chicago that I had never found anywhere else was this instant acceptance of graduate students as future colleagues,” Messbarger says. “Your creativity as a scholar was highly valued.”

The signora would have approved.

Read excerpts from The Lady Anatomist.

Add new comment