At the end of the spring quarter 2010, a giant of the music department will take a bow. Philip Gossett, an expert in Italian opera and the Robert W. Reneker distinguished service professor in music, Romance languages and literatures, and the College, will no longer be a full-time faculty member at the University of Chicago, his professional home for more than 40 years. It is, by all accounts, the end of an era.

In academic circles, Gossett is best known for his creation of critical editions—historically accurate texts—of operas from the early 19th century. Dismayed by a lack of consistency in available operatic texts, he chose a scholarly focus that “bucked the musicological establishment of the 1960s,” says music department colleague Anne Robertson. As a doctoral student in the mid-1960s, when Gossett informed his dissertation advisers at Princeton that he wanted to study the works of the composers Rossini, Donizetti, Verdi, and Bellini, he says they looked at him as if he was a lost cause. Nineteenth-century bel canto was considered trivial, and he was encouraged to study more “important subjects,” such as Wagner, and medieval or renaissance music. “Well, I was very stubborn,” Gossett says. “I did what I felt like doing. I always have.”

Luckily, in 1968, Gossett found an intellectual home at the University of Chicago, a place where “serious research was, and still is, treasured,” he says. “No subject is discouraged because nobody knows what’s going to be important and how one’s scholarship is going to develop. I was given all kinds of moral support to do my work.” As a graduate student, Gossett chose a scholarly focus that "bucked the musicological establishment of the 1960s." Case in point: in 1975, after reading an interview with Gossett in which he lamented the lack of a critical edition of Verdi’s Aïda, the editor-in-chief of the University of Chicago Press at the time, John Ryden, offered to publish the complete critical works of Verdi. Gossett was incredulous. “John,” he said, “you’re talking about a 40-year project.” Ryden replied, “We’re used to it! We’re the University of Chicago Press. We’ll be around.”

Gossett’s distinguished résumé includes a wide array of publications and awards. He is the general editor of both the Works of Giuseppe Verdi and the Works of Gioachino Rossini. His 2006 book Divas and Scholars: Performing Italian Opera has earned numerous honors. In 1998, the Italian government awarded him the Cavaliere di Gran Croce, its highest civilian honor, and in 2004, Gossett was the first musicologist to receive the Mellon Distinguished Achievement Award. During his tenure as dean, the Division of the Humanities began publishing Tableau, and the newsletter has connected the Division with alumni and friends for more than a decade.

On February 22, colleagues, former and current students, and administrators paid tribute to Gossett with a day of events including a symposium, reception, and opera recital. Presenters at the symposium included Hilary Poriss, AM’93, PhD’00, Gossett’s former student and an assistant professor of music history at Northeastern University. “I’m doing the work I do largely because of Philip,” says Poriss. “There’s no other way to explain it.”

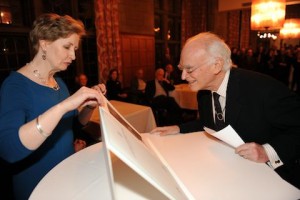

Others echoed Poriss’ gratitude and reverence throughout the day, and at the reception a handful of well-wishers paid formal tribute to the musicologist. Among them were University President Robert J. Zimmer and emeritus trustee Richard Franke. Music department colleague Berthold Hoeckner helped to present Gossett with a special gift: an 1832 letter written by Rossini to the Austrian mezzo-soprano Carolina Ungher, a woman whose “nobility of bearing and dignity of actions commanded attention” from the moment she entered the stage. “That doesn’t just apply to divas but to divos as well,” added Hoeckner, affectionately alluding to the day’s honoree. Later in the evening, in Mandel Hall, renowned mezzo-sopranos Joyce DiDonato and Vivica Genaux performed a selection of arietti by Verdi and Rossini, as well as works by Beethoven and Gilbert and Sullivan, for an enraptured Gossett who sat in the front row with his wife, Suzanne.

The tributes were emotional for Gossett, who felt honored by the return of so many of his former students and colleagues, but when asked if this next step is a modified sabbatical or a retirement, he insists, “I don’t really see any change in my life in the slightest.” At the symposium, In the coming years, the 68-year-old Gossett is unlikely to depart the University entirely. Don Randel, current president of the Mellon Foundation and president emeritus of the University, praised Gossett’s prodigious energy. “Strength to your arm,” he thundered. “Keep it up!” Music department colleague Shulamit Ran teased the scholar, “What does this retirement mean to us? You really are going to be here a lot.” And Franke declared, “I refuse to use the ‘R word.’ You’re on the cusp of another period in your life.”

In the coming years, the 68-year-old Gossett is unlikely to depart the University entirely. He says he will continue to advise undergraduate theses and doctoral dissertations as long as “there are students who want to do so.” He has even offered to teach one or two more courses starting in 2011 or 2012, explaining, “Teaching at the University of Chicago is wonderful because the undergraduate and graduate students here are just fabulous. They are such fun to teach.” He will continue to teach courses as a faculty member at Sapienza University of Rome. Also in his so-called retirement plans are two forthcoming books: one, a musical biography to address the theory and practice of the genre in literary and artistic fields, and the other, a brief, works- and composer-centered history of music. Always interested in the process of translating text into performance, Gossett will continue to research and write critical editions of Rossini compositions, advising and consulting with international opera houses and performers to bring his work to life on the stage.

Add new comment