Contemplating the death and destruction likely to follow from the first successful nuclear test, physicist Robert Oppenheimer was well known for quoting a line from the Bhagavad Gita, “Now I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds.”

The Gita, as it is familiarly known, is one section of the Mahabharata, a Sanskrit poem dating to about 300 BCE that is one of South Asia’s great epics. Depending on the version, the Mahabharata is seven to eight times as long as the Iliad and Odyssey combined.

Gary Tubb, the Anupama and Guru Ramakrishnan Professor in Sanskrit Studies in the Department of South Asian Languages and Civilizations, describes it as “bigger in every way than anything else.” As a result, Tubb is thrilled to be involved in a comprehensive translation of the epic: “something I’ve wanted to see happen all my life.”

A complete translation of the Mahabharata from the critical edition of the text was the dream of J. A. B. van Buitenen, who came to the University as a research associate in 1957, two years after the Committee on Southern Asian Studies was established. The Department of South Asian Languages and Civilizations (SALC) was formed in 1966. Subsequently a professor of Sanskrit and Indic Studies and then SALC chair, van Buitenen translated the first five of the epic’s books—which are still in print today—but died in 1979 before he could finish the remaining 13. The project is now in the hands of James L. Fitzgerald, AB’71, AM’74, PhD’80, van Buitenen’s student and a professor at Brown, with Tubb as associate editor, and Tubb expects to see the work finished before he retires.

South Asian Languages and Civilizations professor A. K. Ramanujan, who died in 1993, famously said, “No Hindu ever reads the Mahabharata for the first time,” because over the centuries its stories have become interwoven throughout South Asian literature, music, and visual art.

For example, Nell Hawley, a third-year graduate student in SALC, studies plays and poetry from the medieval and classical periods in India inspired by the Mahabharata, which she calls “a text you can work on your entire life and never get bored.”

“It’s not just tragic because everybody dies.”

“It’s a peculiarly modern story in a lot of ways,” says SALC associate professor Whitney Cox, PhD’06, who calls the Mahabharata the first Sanskrit text he fell in love with and teaches it in the College Core as part of Readings in World Literature. The narrative employs flashbacks and flash-forwards, and, Cox says, “the moral gray areas of all our major characters are substantial, up to and including Krishna, who’s God.”

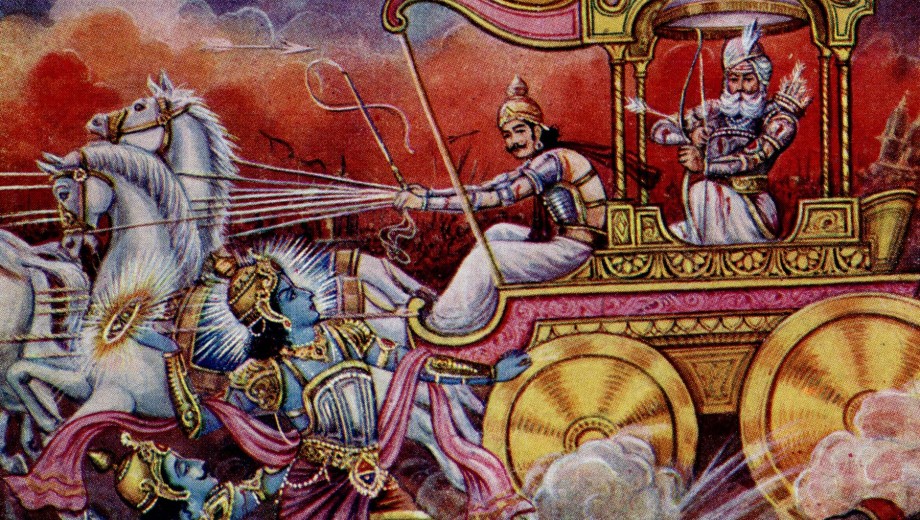

The Mahabharata tells the story of an apocalyptic war between the five Pandava brothers—the heroes of the story—and their cousins, the Kauravas, who are the villains. The text, taking up 18 to 19 large bound volumes, contains numerous digressions: an explanation of the beginning of the universe, Aesop’s fable–like tales, legal texts, prayers, and hymns.

The Mahabharata also illustrates the impossibility of living a truly moral life, according to Wendy Doniger, the Mircea Eliade Distinguished Service Professor of the History of Religions, “because in a number of the most important situations in life, there are two conflicting things that you ought to do.”

For example, Arjuna, the third Pandava brother, hesitates to go into battle against his cousins, knowing he will have to kill innocent people. Krishna appears to him and persuades him that the victims’ lives are not important, only their immortal souls. More important, Krishna says, by not fighting and killing the enemy, Arjuna will endanger the lives of his parents and other innocent people depending on him for protection.

“If he does his job, he’s going to kill a lot of good and innocent people,” says Doniger. “There’s no way he can do the right thing. And that happens all the time in the Mahabharata. It’s a tragic book. It’s not just tragic because everybody dies—and everybody does die. It’s tragic because everybody fails to do the right thing.”

Although it’s not a religious text in the sense of the Bible or Qu’ran, Doniger says, “If you define religion as dharma, which is the Hindu law of the way a human being should live her life, then the Mahabharata is a great Hindu religious text.”

The language of the Mahabharata

Like the Mahabharata, Sanskrit is interwoven throughout South Asian history, scholarship, and culture. The language of the earliest Hindu and Buddhist scriptures, Sanskrit was the primary scholarly language in South Asia for centuries and is still the primary language of Hindu religious ceremonies.

Doniger refers to South Asia’s tradition of scholarship and literature, dating back thousands of years, as “intertextuality in the most intense way. Every text you read is in conversation with other texts, which ultimately are Sanskrit texts.”

Linguistically or culturally, Sanskrit is related to all of the ten other South Asian languages taught at the University of Chicago—more than any other university outside South Asia. As one of the three prominent ancient scholarly languages along with Greek and Latin, Sanskrit was the first foreign language taught at the University.

As SALC marks its fiftieth anniversary, a $3.5 million gift in January from Guru Ramakrishnan, MBA’88, and his wife Anupama to endow Tubb’s professorship, will help the department to sustain its tradition in South Asian scholarship, the future of which is increasingly moving beyond simply studying the language as “a musty old artifact,” says Tubb, who is also faculty director of the University’s Center in Delhi.

“There’s a much more active interest now in history and in the historical setting of Sanskrit texts: their economic, their political, their military history,” he says. “It’s so much livelier than in the past.”