Most English departments like to think of themselves as interdisciplinary. But for David Simon, “there’s something special” about the way that University of Chicago literary scholars cross boundaries.

“Interdisciplinarity is not an ideal. It’s just a fact,” says Simon, who studies dispassion in sixteenth- and seventeenth-century British literature. “We’re constantly in conversation with people with very different expertise from our own.”

The research interests of the 13 assistant professors in UChicago’s Department of English Language and Literature span geography, history, media, and methodology. Some, like graphic narrative expert Hillary Chute and digital media and video game scholar Patrick Jagoda, work in emerging subfields; others, like eighteenth-century experts Heather Keenleyside, AM’03, PhD’08, and Timothy Campbell, are building on the department’s long tradition of scholarship rooted in historical periods.

It’s an exciting time for the department, which has hired nine assistant professors in the past three years. “Fields are being defined and made, fields that other English departments are just starting to think about,” says new hire Sonali Thakkar, whose first book will focus on the memory of the Holocaust in postcolonial literature.

The group is united by an interest in “intellectual problems more than predefined categories,” says John Muse, who is at work on a book about theatrical brevity in the twentieth century. “That generates a lot of exciting cross-fertilization of people from different periods talking to one another and to people across the University.”

Chair and professor Elaine Hadley says the department has deliberately sought such “ambidextrous” scholars. The department is increasingly alert to changes in the discipline, such as a growing emphasis on transnational literature and “a more capacious sense of genre.”“Fields are being defined and made, fields that other English departments are just starting to think about.” Yet Hadley also thinks the department’s overarching goal remains unchanged. Whether the object of study is a video game or a Victorian novel, she says, “Our field has always [tried to] interpret cultural and aesthetic production.”

Both Jagoda and Chute, whose objects of study lie somewhat outside the mainstream, say their work is rooted in the same kind of analysis that literary scholars have applied to more traditional texts. “With video games, ‘close play’ is just as important as close reading,” says Jagoda. “You don’t know whether a game is working or how it’s working until you’ve picked up a controller or put your fingers on the keyboard.”

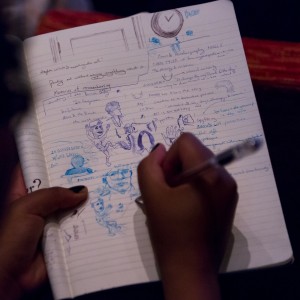

“A lot of people don’t know how to close read an image,” echoes Chute, a Neubauer Family assistant professor who studies comics. She urges her students “to think about what affects them about the image and why—to look and then look again. Part of what I’m hoping to call attention to is how the comics page is trying to make a reader slow down.”

For Campbell, the continued emphasis on careful scholarship grounded in primary sources is a hallmark of the department. “[There’s] a kind of faithfulness to the actual objects out there in the world that we’re trying to explain,” he says.

Along with studying new genres and forms, junior faculty members are developing new modes of research. Richard So is at work on a collaborative digital humanities project that explores connections among modernist poets in China, Japan, and the United States. His first book will examine a community of Chinese and American writers and intellectuals that included Pearl S. Buck. Reliance on new technology doesn’t fundamentally change his scholarship, he says: “It’s just a way of telling the same stories [on a] much more massive empirical scale.”

Christopher Taylor shares So’s interest in global literary communities. Taylor’s research examines how literature helped nineteenth-century British West Indians to imagine their relationship to their imperial power. “It provided a means of trying to produce [imaginative] and actual new kinds of communities,” he explains.

One benefit of having such an energetic group of young faculty, says Hadley, is that they’re willing to spread their intellectual energies and imagination across the University. Chute and Jagoda have organized events with the Richard and Mary L. Gray Center for Arts and Inquiry, while Thakkar has helped to develop and will teach a new Core course, Gender and Sexuality in World Civilizations.

Srikanth Reddy and Jennifer Scappettone, practicing poets who teach in the Creative Writing program, also do critical work on poetry. Balancing that work can be challenging, but “it’s a necessary difficulty,” says Reddy, who completed his second book of poetry, Voyager, in 2011. “You have to keep studying the art to keep growing as a writer.”

Scappettone thinks the benefit of joining creative and critical work flows both ways. Many literary texts that made their way into her book on modernism in Venice “were works that I encountered in discussion with my fellow poets,” she says. “They weren’t necessarily works that were being taught in university settings.”

Many of the assistant professors say their most important resource is each other. Adrienne Brown, who studies representation of the skyscraper in American literature, says that her colleagues are not only smart: “They’re curious. They want to know what people are doing across different fields.”

Lunches, coffees, and dinners are regular events among the tight-knit group, says Benjamin Morgan, an expert on Victorian literature, science, and aesthetics. Their closeness caught the attention of a recent job candidate. “We were having drinks,” Morgan says, “and she said, ‘Wow, you guys really seem to like each other.’”

Adds Keenleyside, “It’s a cheerful time. People are quite excited to be in a moment of tradition and innovation at once.”

Get a glimpse of faculty course syllabi.